Rahul Mehrotra: Designing the Contextual, Embracing the Kinetic, and Shaping the Future

Rahul Mehrotra discusses the importance of context in architecture, emphasizing the need to address both local and global forces shaping urban environments. He also advocates for adaptable, temporary urban solutions and a dynamic approach to governance.

Rahul Mehrotra is an architect and urban planner whose work seamlessly integrates the cultural, political, and environmental dynamics of India. As the founder principal of RMA Architects, he has redefined the architectural landscape through projects that blend advocacy, innovation, and social impact. A professor at Harvard University, Mehrotra divides his time between Mumbai and Boston, guiding the next generation of urban thinkers while shaping the built environment through his firm's notable projects. With a career spanning over three decades, his extensive contributions to architecture and urban planning have earned him both national and international recognition. His work is not just about buildings, but about understanding and addressing the deep connections between people, places, and cities. In this interview, Mehrotra discusses his approach to architecture, the role of empathy in design, and his ongoing exploration of Mumbai's unique urban fabric.

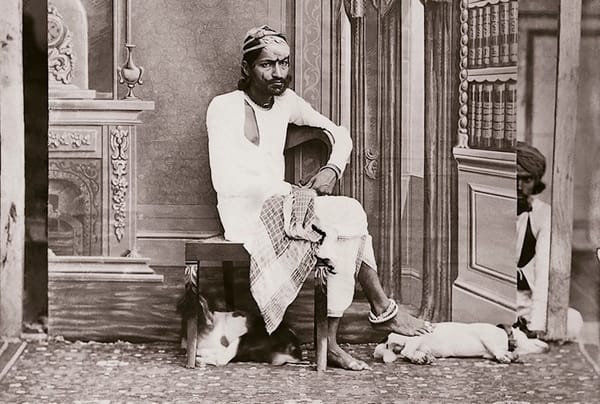

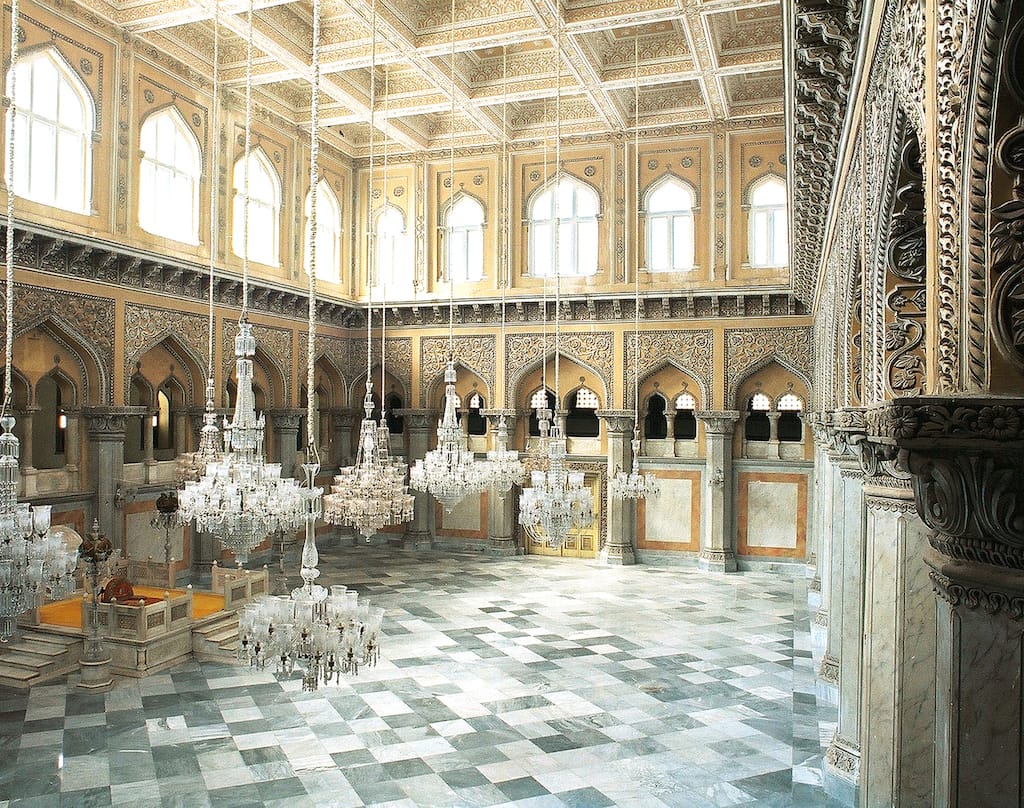

Restoration of Chowmahalla Palace: Spearheaded by RMA Architects, this project revived one of Hyderabad’s earliest neo-classical marvels. Built by Nizam Salabat Jung in the 1750s, the 12-acre complex now integrates restored guest rooms as a crafts centre and the iconic Khilwat, housing a museum of the Nizam’s artefacts. Using traditional craftsmen and techniques, the meticulous restoration preserved granite arches, lime plasterwork, and terracotta balusters, breathing new life into a site once threatened by neglect and urban encroachment. Photo: Rajesh Vora

Nikhil Sardana: Your work spans diverse projects across varied geographies. How do you adapt your architectural practice to address unique cultural settings, environments, and urban challenges?

Rahul Mehrotra: For me, context is paramount. I approach each project by deeply understanding its context, often going beyond the obvious to explore what I term "the context of the context."

Architects are traditionally trained to analyse context through factors such as climate, available materials, craftsmanship, or even the site's history. While these are critical, I believe we must place this understanding within a broader framework. This "context of the context" includes geopolitical forces, regional politics, societal aspirations, and historical underpinnings. By doing so, we discover rich intersections that inspire unique architectural expressions.

This layered approach is what gives each project its distinct character. It reflects my belief that architecture cannot exist in isolation but must respond to the larger forces shaping its environment. For instance, modernism in post-independence India worked as a tool to establish a pan-Indian identity by eschewing regional aesthetics. However, as coalition politics and regional aspirations grew, architecture evolved to embrace local identities, as seen in works like Laurie Baker's in Kerala. This shift underscores how cultural and political contexts directly influence architectural expression.

This philosophy also informs my writing—whether on Art Deco or post-1990 Indian architecture—where I explore how these broader contexts influence design. Over the years, my teaching has further clarified this approach. Teaching, while a generous act of sharing, is also deeply introspective. It forces you to distil and articulate lived experiences, which has profoundly shaped my understanding and practice.

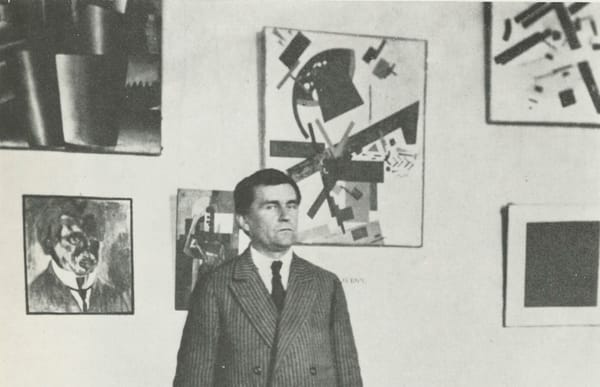

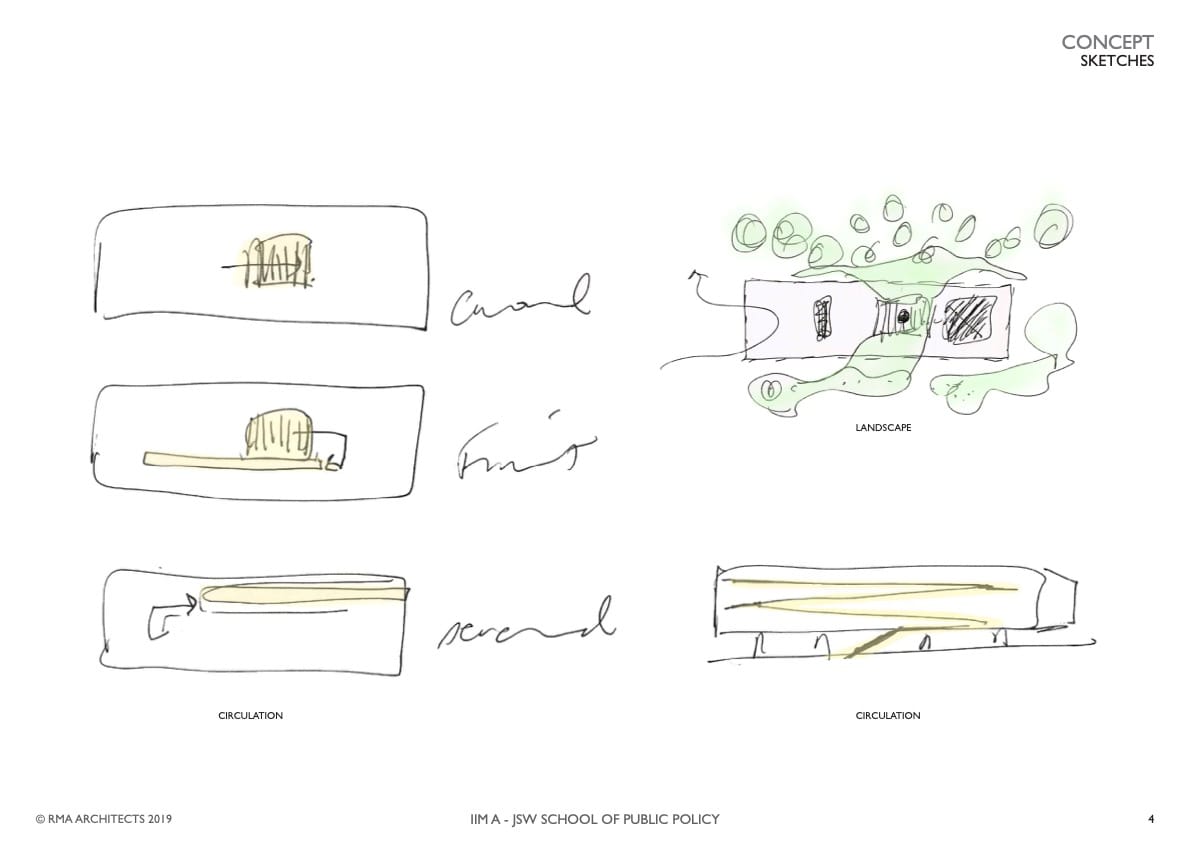

JSW School of Public Policy, IIM Ahmedabad: Designed by RMA Architects, this innovative building reflects the democratic principles of public policy through its flexible and dynamic spaces. The Forum, a central double-height space, serves as both a social and academic hub, fostering collaboration and interaction among students and faculty. With a carefully designed privacy gradient, the building features interconnected spaces that encourage dialogue and research, while the strategically placed louvers provide natural ventilation and visual interest. The architectural design integrates the surrounding landscape, with Peltophorum and Neem trees complementing the building's dramatic façade. Photo: Rajesh Vohra, Vinay Panjwani

NS: You’ve extensively documented Mumbai’s urban landscape. How has the city shaped your architectural philosophy and approach to urban design?

RM: My engagement with Mumbai has profoundly shaped my thinking. My academic journey began at CEPT in Ahmedabad, and later, I studied urban design at the Harvard Graduate School of Design, where I now teach. Urban design, as I learned, is inherently about advocacy. It bridges the narrow focus on the site of architecture with the macro, albeit abstract, vision of urban planning. Architects often focus narrowly on site-specific details like setbacks and FSI, while planners operate in abstractions like land-use maps and policies. Urban design creates a dialogue between these scales, interpreting the physical implications of planning policy. And hopefully designing feedback loops that benefit both.

Working in Mumbai challenged some of the premises I encountered during my studies. Initially, I believed architecture to be a central instrument in city-making. However, my experiences in Mumbai revealed a more nuanced reality. In a city as dynamic and layered as Mumbai, urban design goes beyond static architecture and planning. This realisation led me to conceptualise the "kinetic city," a framework that captures Mumbai’s ever-evolving, ephemeral nature. The kinetic city is about temporary structures, informal networks, and the fluid interactions that define urban life in cities like Mumbai.

Mumbai’s urban landscape has taught me that cities are not just physical entities but living organisms. They thrive on the interplay of formal and informal systems, and understanding this complexity has deeply influenced my practice and philosophy.

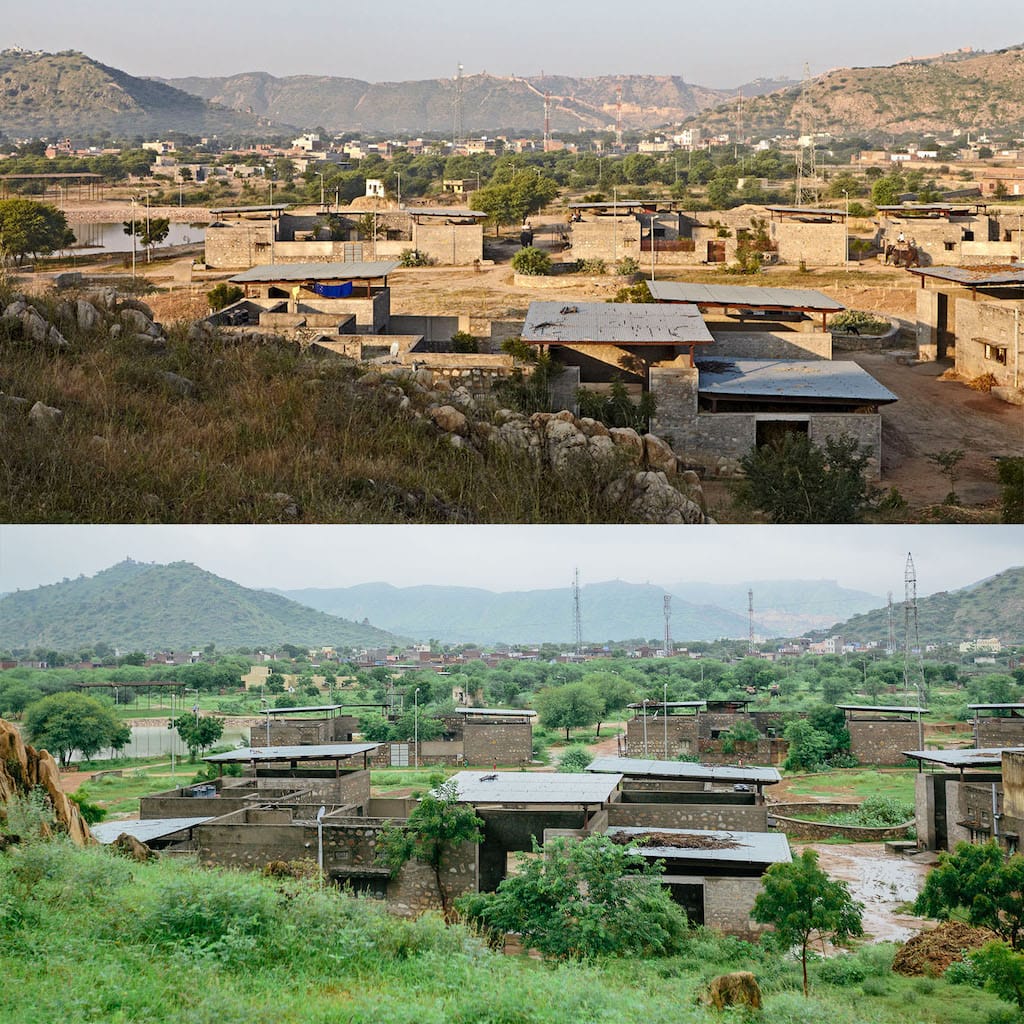

Hathi Gaon: A Housing Project for Mahouts and Elephants. Situated at the foothills of Amber Palace near Jaipur, this project, designed by RMA Architects, focuses on landscape regeneration and sustainable water management in Rajasthan's desert climate. The site, once a sand quarry, now includes water bodies for rainwater harvesting and a tree plantation program to restore local species. The design emphasizes community-building through clustered housing, shared courtyards, and pavilions, while keeping architecture minimal to allow inhabitants to gradually adapt and personalize their homes. Photo: Rahul Mehrotra, Rajesh Vora

NS: One of your standout projects is Hathi Gaon in Jaipur, which combines social housing for elephants and their caretakers. How did you balance functionality, aesthetics, and social responsibility in this project?

RM: This project posed unique challenges. Elephants, suited to water-rich regions like Kerala or Sri Lanka, struggle in a desert climate like Jaipur’s. When approached for this competition, which we eventually won, we framed it as a landscape design initiative rather than solely an architectural one.

The government had allocated only 350 square feet per mahout and elephant—an inadequate amount. Housing, especially low-income housing, is inherently organic and evolves with life. To address the spatial constraints, we incorporated courtyards to expand usable areas. A 350-square-foot house became 450 square feet with a small courtyard, and clustering three houses around a larger courtyard created shared spaces, effectively increasing each family’s access to 700 or 800 square feet.

We also prioritized the landscape, focusing on water access, greenery, and improved living conditions for both the mahouts and elephants. Our aim was to provide a quality of life that often surpasses what is available in urban settings.

This project highlighted the complexity of working with multiple stakeholders—those funding the initiative, managing implementation, and directly impacted users. Architects often act as mediators between these groups. For Hathi Gaon, I was able to bridge these gaps by earning the trust of the mahouts, speaking the technical language of the implementers, and aligning everyone’s aspirations.

Ultimately, this experience taught me that advocacy in architecture requires more than design skills. Balancing functionality, aesthetics, and social responsibility involves deeply understanding and addressing human needs across all levels.

Novartis Campus (Basel, Switzerland) Virchow 16: Designed by Rahul Mehrotra, this building seamlessly integrates laboratories and offices with distinct spatial needs. The atrium, filled with greenery, bridges the height differences between the labs and administrative areas, while staircases and through-views connect the various levels. The western façade, adorned with greenery, anticipates the lush interior, creating a harmonious link between the building’s exterior and interior spaces. Mehrotra's design balances functionality with aesthetics, fostering a dynamic and collaborative work environment. Photo: Iwan Baan

NS: You’ve had an illustrious academic career, currently holding a professorship at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design. How do your academic and professional experiences inform each other?

RM: My entry into academia was somewhat accidental. After graduating, I returned to India and spent 12 years deeply engaged in work without traveling abroad—I didn’t even use my passport for eight or nine years. During this period, I focused on writing, advocacy, and grounded practice. Teaching wasn’t something I initially considered, and I didn’t actively seek out opportunities to teach in architectural schools.

However, through a series of chance encounters, my wife Nondita and I were both offered teaching positions at the University of Michigan. Initially, it was meant to be a one-semester stint, but we found the experience incredibly rewarding and eventually returned. Later, I transitioned to MIT and eventually to Harvard. If someone had asked me in 2002 about my academic aspirations, I would have said, “None at all.” But as the saying goes, life is what happens while you're making plans.

Teaching has been transformative for me. It not only comes naturally, but I genuinely enjoy it and learn a great deal from the process. It informs my practice in profound ways because I strive to “walk the talk.” What I teach my students must align with what I build. This commitment has led me to take on projects that embody the principles I teach—even if it means operating at a financial loss. The goal is to ensure I can confidently present these projects to my students, knowing they are consistent with the values I impart in the classroom.

School of Arts and Sciences, Ahmedabad University: Designed to foster interdisciplinary learning, this building by RMA Architects encourages spontaneous interactions between students and faculty from diverse cultural backgrounds. The strategic location near a historic building and campus entrance led to the decision to create a porous ground floor, ensuring easy access to both the new building and the repurposed historic structure. The design features a triple-height lobby as a social hub, surrounded by flexible spaces like classrooms, research labs, and seminar halls to facilitate cross-disciplinary engagement. The building also incorporates sustainable design elements, such as a double façade with operable louvers and integrated planting areas, to reduce heat and dust in Ahmedabad's hot, dry climate. Photo: Vinay Panjwani, Vivek Eadara

NS: What emerging trends do you see shaping the future of architecture, particularly in terms of the evolving role of architects and urban planning?

RM: One of my recent projects involved collaborating with students to document 41 young architectural practices in South Asia, resulting in a book titled Architectures of Transition. This initiative was born during the pandemic, with the aim of providing a platform for young architects whose early careers were disrupted by the global crisis. The project began as a virtual lecture series and evolved into a book co-authored with two of my students – Devashree Shah and Pranav Thole. It captures remarkable trends among young architects who are redefining the field.

These architects are inventing new client constituencies, engaging in cross-subsidy models—such as designing homes for affluent clients while undertaking community projects in rural areas—and challenging traditional norms. They exemplify a multiplicity of practice, balancing teaching, research, advocacy, and building. This multifaceted approach allows for a deeper understanding of context and enables them to address the gap between the increasing spheres of concern (like climate change and social justice) and their immediate spheres of influence.

I believe this shift toward a diverse mode of practice will shape the future of the profession. Architects must engage with civil society as a core client, recognizing that society invests in architects to envision better spatial possibilities for living. This approach not only elevates the role of architecture but also empowers architects to negotiate effectively with powerful forces.

When it comes to planning and urbanism, context remains paramount. While concepts like the 15-minute city and the green city have gained popularity, applying universal solutions indiscriminately can be counterproductive. Each city—be it Dubai or Mumbai—has unique challenges that require tailored approaches. Broadly, however, aligning urban design with climate change mitigation and fostering equitable spaces will continue to be key priorities for future generations.

LMW Corporate Headquarters: Designed by RMA Architects, this harmonious blend of traditional elements and modern sensibilities is structured around three courtyards with water bodies, locally sourced materials, and artistic installations. Responding to Coimbatore's climate and cultural heritage, the building redefines the corporate office with a thoughtful integration of regional architectural traditions and contemporary functionality. Photo: Rajesh Vora

NS: Climate change is a critical concern. How do you see architecture and urban design addressing this global challenge?

RM: What concerns me about the current discourse on climate change is that we are excessively focused on redefining and reiterating the problem rather than taking actionable steps for moving from the critical to the propositional.. Architects and designers, as imaginative spatial thinkers, have the unique ability to lead in devising innovative solutions. Yet, much of the current effort globally, including in cities like Manhattan, revolves around buffering strategies—defensive measures aimed at mitigating immediate threats, such as rising sea levels. These measures often prioritize protecting valuable real estate over long-term sustainability, driven by capitalism and short-sighted goals.

Take Mumbai as an example: projections indicate that iconic areas like Marine Drive could be underwater in two decades. Despite this, there is minimal effort to rethink the regional urban plan comprehensively. The opportunity lies in recognizing high-ground areas, such as Navi Mumbai, as critical to future urban resilience. Initiatives like building an airport there, maybe by default, are steps in the right direction, but much more needs to be done.

The larger issue is that our planning culture has become reactive rather than proactive. Historically, forward-looking projects like the conceptualization of New Bombay by visionaries such as Charles Correa, Shirish Patel and Pravina Mehta were exceptional. Today, we seem content to address problems only as they arise, a shift from avant-garde planning to rearguard action. This lack of anticipation is particularly dangerous in the context of climate change.

Planning must return to a speculative and propositional mode, embracing the possibility of errors but fostering critical conversations and solutions. It’s imperative that architects, planners, and policymakers develop and promote frameworks for anticipating future challenges. Only by changing this culture of planning can we hope to mitigate the chaos that awaits if we continue on our current trajectory.

Three Court House: Designed by RMA Architects as a series of modular units, each organized around a courtyard, this residence harmonizes with its village surroundings. The incremental planning allows adaptability, while a privacy gradient and collapsible spaces ensure flexibility. Outbuildings for a clinic and staff residences create a thoughtful interface with the community, blending functionality with cultural sensitivity. Photo: Rajesh Vora

NS: Your research on the Kumbh Mela offers valuable insights for urban design. What lessons can cities like Mumbai or Bangalore learn from this ephemeral city?

RM: The Kumbh Mela offers profound insights for urban design, particularly for rapidly expanding cities like Mumbai, Delhi, or Bangalore. Two key lessons stand out:

- The Ephemeral Approach:

The Kumbh Mela demonstrates the power of designing for temporality. The entire city, accommodating millions, is constructed using a kit of parts: bamboo, rope, textiles, plastic, and corrugated metal. These materials are assembled into functional, adaptable structures, emphasizing flexibility over permanence. This approach challenges the conventional mindset of creating permanent solutions for often temporary needs. - Governance as a Dynamic System:

The governance model of the Kumbh Mela operates on a temporal hierarchy. Initially led by the Chief Minister, authority transitions to bureaucrats, and ultimately to the Mela Adhikari, who wields near-autonomous control during the event. This fluid delegation ensures efficient, responsive decision-making. Adopting a dynamic governance model like that of the Kumbh Mela could transform urban administration, enabling cities to respond swiftly and effectively to crises, including those arising from climate change. These lessons underscore the need for a paradigm shift in how we plan, build, and govern urban spaces. Cities must embrace ephemerality and nimbleness, both in their physical structures and administrative frameworks, to meet contemporary challenges and ensure sustainable growth.

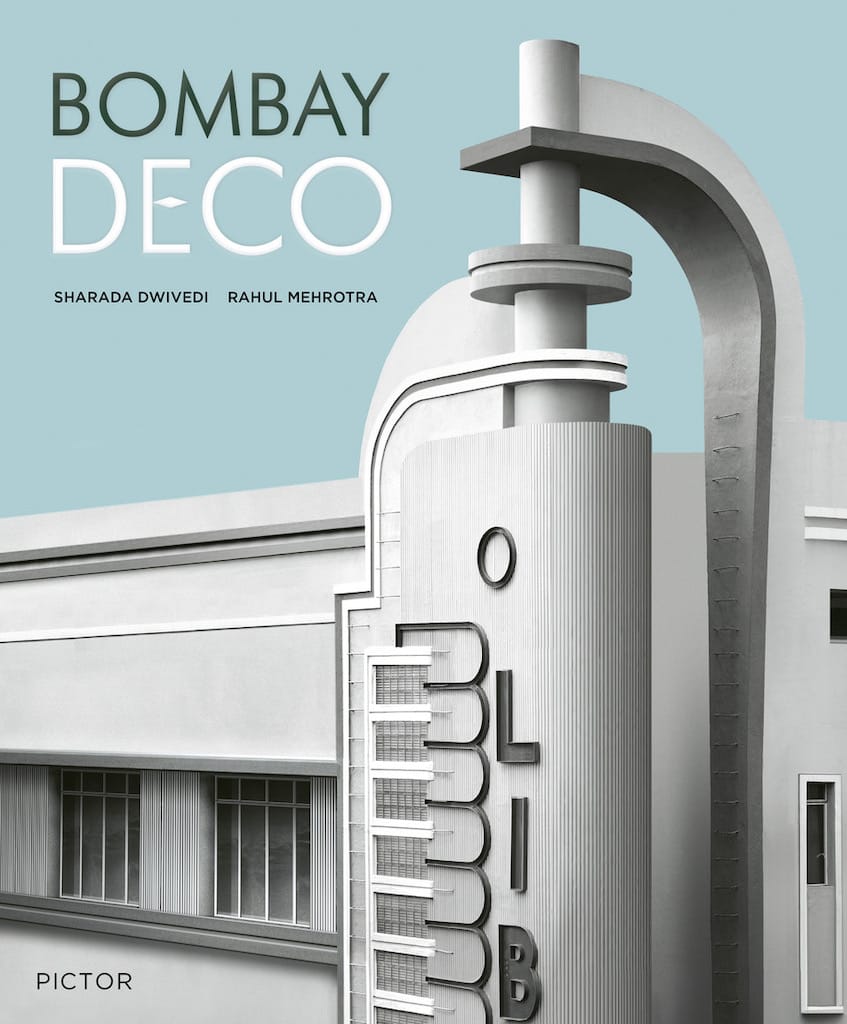

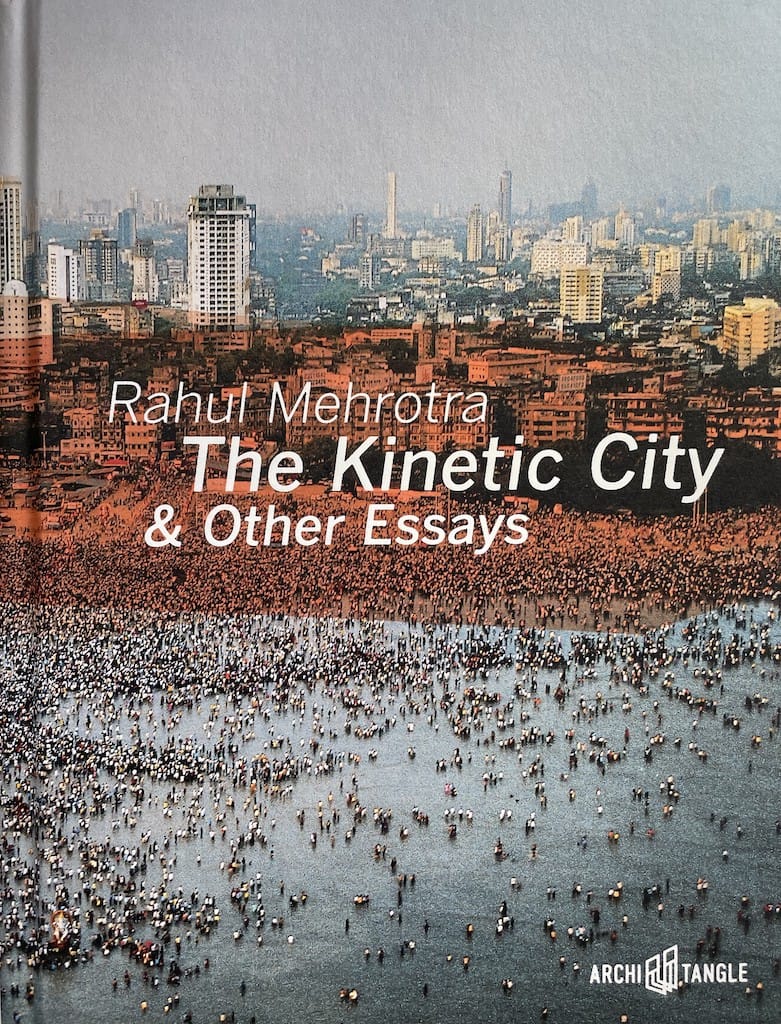

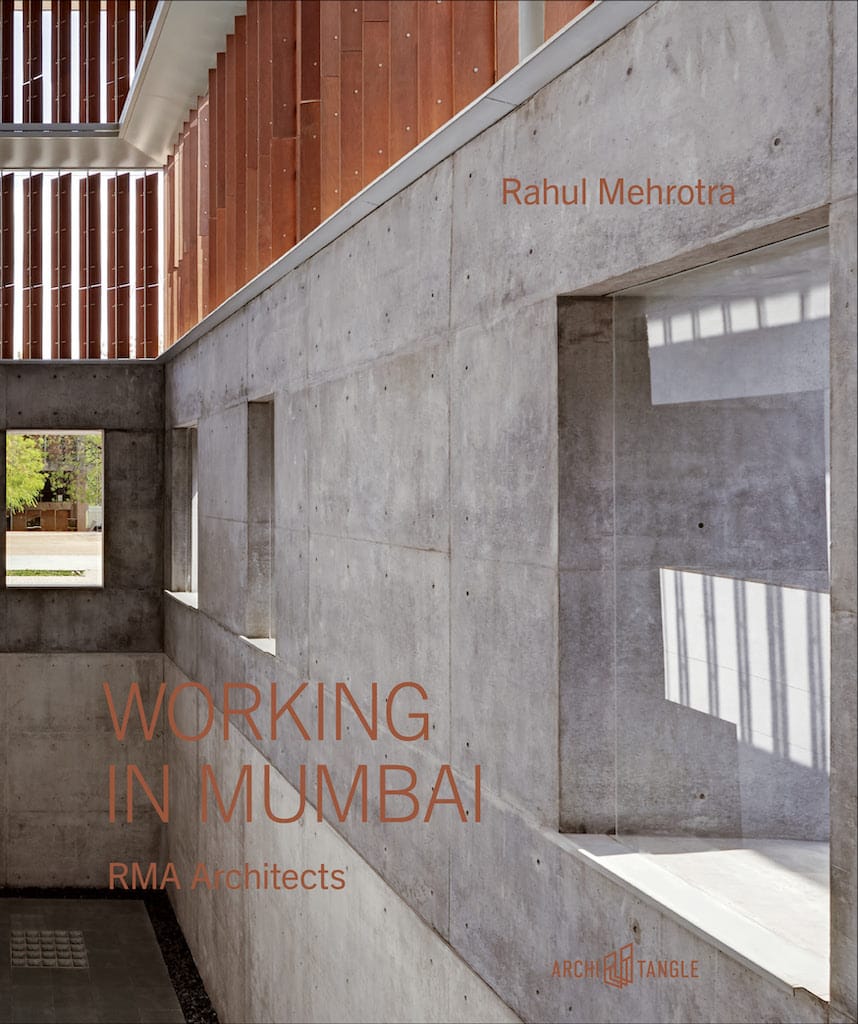

Working in Mumbai by Rahul Mehrotra reflects on 30 years of RMA Architects’ practice, exploring the intersections of architecture, urbanization, and Mumbai's unique context; the book delves into challenges faced by architects in rapidly urbanizing regions, weaving a narrative of teaching, research, and practice; curated projects unravel the evolution of the firm and the city. BOMBAY DECO by Sharada Dwivedi and Rahul Mehrotra celebrates Mumbai’s Art Deco heritage, tracing its transformation into a cosmopolitan metropolis with the bold Indo Deco style; it highlights the city’s embrace of modernity through architectural innovation and commemorates UNESCO’s recognition of its Victorian Gothic and Art Deco ensembles as a heritage precinct. The Kinetic City & Other Essays by Rahul Mehrotra introduces the transformative concept of the Kinetic City as a counterpoint to the Static City; curating three decades of Mehrotra’s writings, the book offers a framework for understanding the fluid and dynamic nature of urban spaces; complemented by Rajesh Vora’s evocative photo essay, it explores themes of transaction, spectacle, and habitation in contemporary urban design.

NS: With such a prolific career, what are your aspirations for the future—for India, your practice, and your students?

Rahul Mehrotra: Currently, I’m working on a book titled Becoming Urban, co-authored with a former student Sourav Biswas. It examines India's urbanization trajectory, focusing on how resources are concentrated in major cities, leaving smaller towns neglected. India has over 7,000 towns, but only a handful receive adequate attention, resulting in a lack of infrastructure in settlements (defined sometimes as villages ) with populations over 100,000. Through this book, we hope to shift the conversation toward these overlooked areas.

I also advise young architects to consider opportunities in smaller towns rather than major cities like Mumbai or Delhi. These towns offer unique opportunities for innovation and community impact. Moreover, we need to rethink housing in India. The traditional model, assuming a nuclear family, is outdated. We should create more adaptable housing for migrants, like transient accommodations, which became especially clear during the pandemic.

Ultimately, I hope the next generation of architects will move beyond vanity projects and embrace their role in improving society. The real pioneers will emerge from smaller towns, where architects can respond to untapped challenges and create spaces that transform lives.