What does “Impressionism” mean?

Claude Monet’s 'Impression, Sunrise' exemplifies Impressionism with its focus on light and atmosphere over detail. Initially ridiculed, it named the movement and highlighted fleeting moments and middle-class leisure in art.

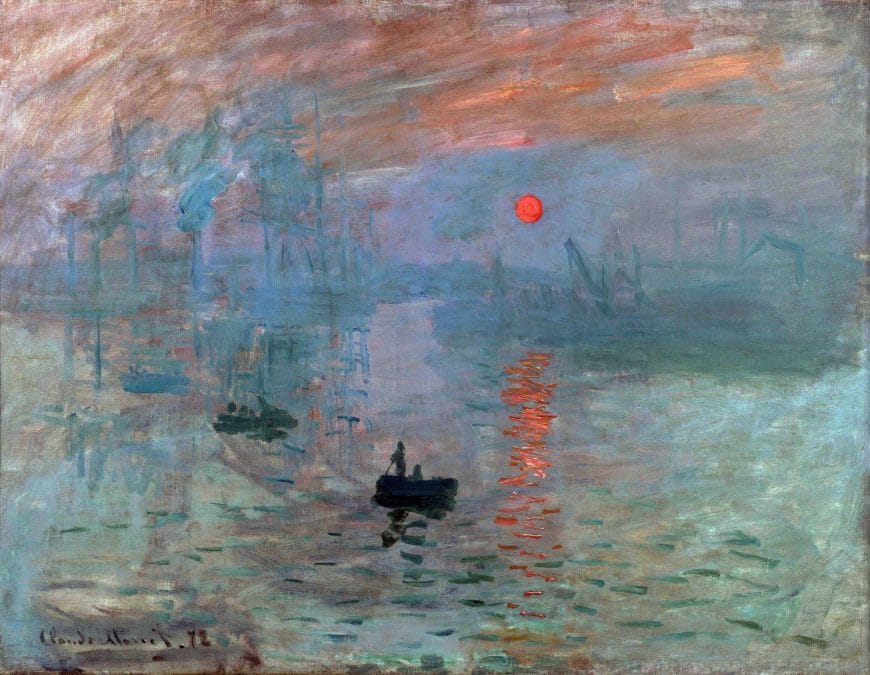

Claude Monet’s Impression: Sunrise is an exemplary Impressionist painting in several ways, not least of which is its title. It depicts a misty harbour scene at Le Havre (a port city in Northern France) in which boats and figures are reduced to flat, shadowy silhouettes, while the red light of the sun reflected on the water takes on tangible form in highly visible brushstrokes.

What we see when we look at the painting is unquestionably painted; Monet made no effort to develop his suggestive image into a more detailed and finished rendering of the scene. The loosely sketched silhouettes of boats exemplify the difficulty of seeing objects in the mist with the sun rising behind them. Monet embraced this difficulty, using it as an occasion to display a painterly rendering that says more about the momentary light and atmospheric conditions than it does about the objects in the scene.

Ask yourself: is there anything in the painting that tells you this is Le Havre? In an interview Monet acknowledged the failure of the painting to depict a recognizable place. When he was asked for the title of the painting for the catalogue of what later became known as the first Impressionist exhibition he said: “I couldn’t very well call it a view of Le Havre. So I said: “Put Impression.” With this decision Monet unwittingly named an art movement, and this work’s emphasis on brushwork, light, and atmosphere at the expense of the clear representation of objects became a hallmark of the Impressionist style.

Impressionism was not always so well-loved

It may be surprising to know that an art movement so well-loved today—highly successful at auction, the subject of numerous blockbuster exhibits, and a vast number of popular publications—was subjected to a good deal of scorn and ridicule in its early years. Even the term “Impressionism” was first used pejoratively in relation to the new art first exhibited in 1874 by the Société anonyme cooperative d’artistes peintres, sculpteurs, etc. (Anonymous cooperative society of artists, painters, sculptors, etc.). These artists used the term “anonymous” quite intentionally—they wanted to avoid imposing a restrictive label or common agenda on their group, whose members employed a variety of styles and painting techniques. Ultimately, they staged eight exhibitions between 1874 and 1886.

The group included a number of artists who became the most famous Impressionists: Gustave Caillebotte, Mary Cassatt, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro, Pierre Renoir, and Alfred Sisley, as well as many other artists (some of whom are now associated with later modern art movements such as Post-Impressionism or Symbolism). Despite their eclecticism, contemporary viewers and the critics who reviewed the Société anonyme’s exhibitions expected the group to share common goals and characteristics, and the label “Impressionism” soon came to identify a new artistic movement, with some of the artists of the Société anonyme at its core.

A mere impression

The critic Louis Leroy was the first to emphasize the term “impression” in relation to the new painting, adopting it from Monet’s Impression: Sunrise in a satirical dialogue entitled “Exhibition of the Impressionists” that was published in the popular illustrated magazine Le Charivari. Leroy found Monet’s use of “Impression” in his painting’s title particularly appropriate because it suggested that the work was unfinished according to Academic conventions of representation; that is, it represented a mere impression of the scene, rather than a fully structured and completed work of art. Leroy repeatedly emphasized the term “impression” in the dialogue and described many of the paintings by Monet and his fellow exhibitors as sloppy and slapdash, going so far as to compare Monet’s Impression: Sunrise to embryonic wallpaper and Pissarro’s Hoarfrost to paint scraped off of a dirty palette.

Despite this prominent early critical association of the term “impression” with sloppiness, two years later “Impressionism” and “Impressionist” were being widely used to label the new art by its supporters as well as its detractors. It was undoubtedly the flexibility of the term that allowed it to be so widely adopted, but with that flexibility came a certain amount of confusion about the aims of the movement.

Leroy’s usage suggests a hasty and inaccurate “first impression,” but the term also has a very precise and technical connotation as a scientific word designating the stimulation of the optical or other sensory nerves. This scientific definition implies a project of careful observation and objective documentation, but the term is also used for a more subjective and individual response, as when one gives one’s own “impressions” of a person, place, or thing. Hasty generalization or precise observation? Objective documentation or subjective interpretation? All of these contradictory qualities have been associated with the Impressionist movement.

How useful is the term “Impressionism”?

The complex significance of Impressionism expands further when we examine the characteristics emphasized in scholarly and popular writings about the movement. Two quite different artistic projects and sets of characteristics are commonly associated with Impressionism:

First, a painting is called Impressionist if it exhibits a certain style, consisting of patchy brushwork and a light pastel colour scheme that aims to capture transient effects of atmospheric lighting, as can be seen in Sisley’s Autumn: Banks of the Seine near Bougival.

Second, a painting is called Impressionist if it exhibits a certain type of subject matter, typically plein-air (painted out-of-doors) scenes of middle-class men and women at leisure: drinking in cafés, boating, swimming, attending horse races, promenading in gardens, and similar activities.

Berthe Morisot’s painting The Harbor at Lorient, which was shown in the first exhibition of the Société anonyme, exemplifies this second characteristic. We see a very well-dressed bourgeoise woman resting while out for a stroll in the town of Lorient in France. The figure’s white dress and parasol appear somewhat incongruous on the dirty stone wall overlooking a working harbour.

However, not all of the art works shown by members of the Société anonyme exhibit both of these characteristics; in fact, some exhibited neither. The works of Camille Pissarro are typically in the Impressionist style, but as his painting Hoarfrost indicates, he frequently painted the working class at labour rather than the middle classes at leisure. Edgar Degas and Gustave Caillebotte frequently painted the middle classes at leisure, but did not employ the characteristic Impressionist style.

This terminological confusion has led some historians to wish to discard the term Impressionism altogether, but whatever label or labels are attached to them, these two projects—capturing the evanescent effects of atmospheric lighting, and depicting scenes of contemporary middle-class leisure—were significant artistic tendencies in Paris and, slightly later, in the wider Euro-American scene starting in the 1860s and 70s. Rather than attempt to limit the definition of the Impressionist project, we embrace the flexibility of the term.

This article first appeared on Smarthistory.org.