Were the Old Masters Really Working Alone? Inside the Renaissance Atelier

Romantic myth of the solitary genius falls apart when we examine bustling Renaissance and Baroque studios. Uncover how Leonardo, Raphael and Titian led collaborative ateliers, training apprentices who shaped the great masterpieces we revere today.

We often envision the Old Masters—Leonardo da Vinci, Raphael, Titian—as solitary geniuses, labouring alone in their studios to produce the masterpieces we revere today. The romantic image of the lone artist, brush in hand, consumed by divine inspiration, has long permeated art history and popular imagination alike. Yet this portrayal obscures the collaborative realities of early modern workshops, where studio apprentices and assistants played indispensable roles. Rather than solitary creators, the great painters of the Renaissance and Baroque eras typically presided over bustling ateliers, guiding teams of pupils through every stage of artistic production. In this article, we will explore the studio apprentice system, examine key case studies, and reconsider what it truly meant to be an “Old Master” in an era defined as much by collective craftsmanship as individual genius.

The Medieval Roots of Artistic Workshops

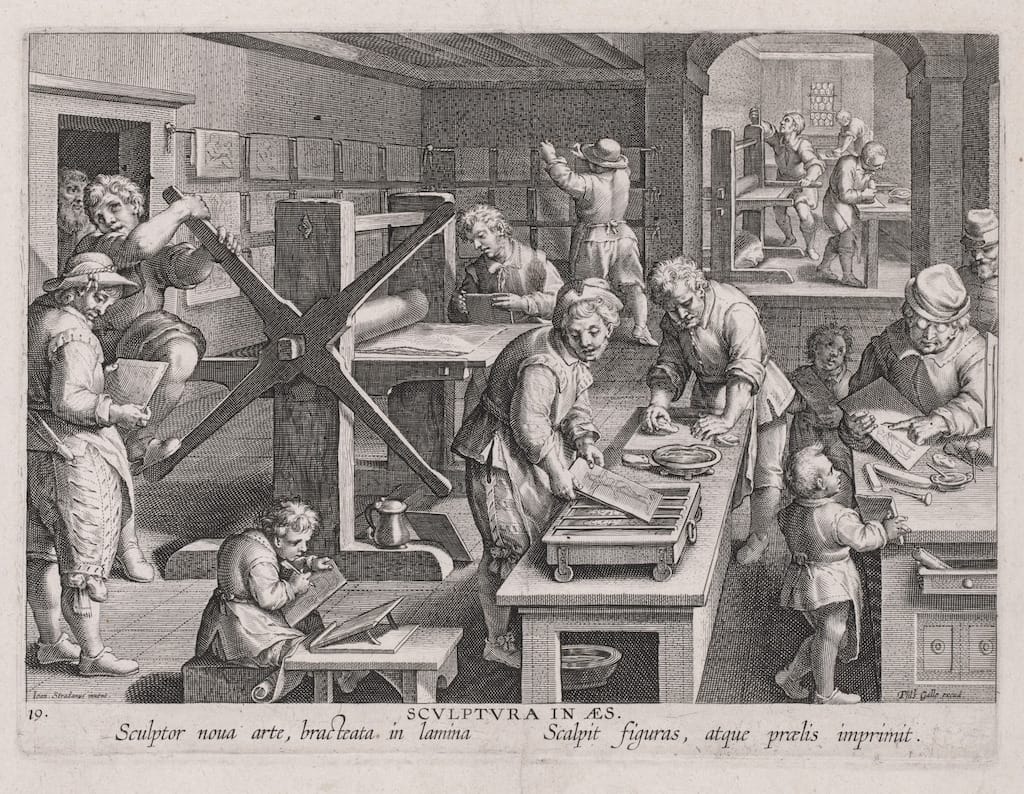

Long before Leonardo sketched his flying machines, medieval Europe organised artistic production through guilds and workshops. Sculptors, painters and illuminators belonged to craft guilds that regulated training, quality and trade secrets. Apprentices—usually boys of around twelve years of age—would enter a master’s workshop and spend several years learning the foundational skills of drawing, pigment preparation, tool maintenance and perspective. They progressed to journeyman status only once their master judged them competent to undertake paid commissions.

This system served several crucial functions. First, it safeguarded quality by ensuring that all works bearing a master’s signature met stringent standards. Second, it transmitted technical knowledge—such as the preparation of tempera and, later, oil paints—through hands‑on practice rather than purely theoretical instruction. Lastly, it produced a steady labour force capable of handling large, complex commissions: altarpieces, fresco cycles and illuminated manuscripts.

The Renaissance Workshop: From Florence to Rome

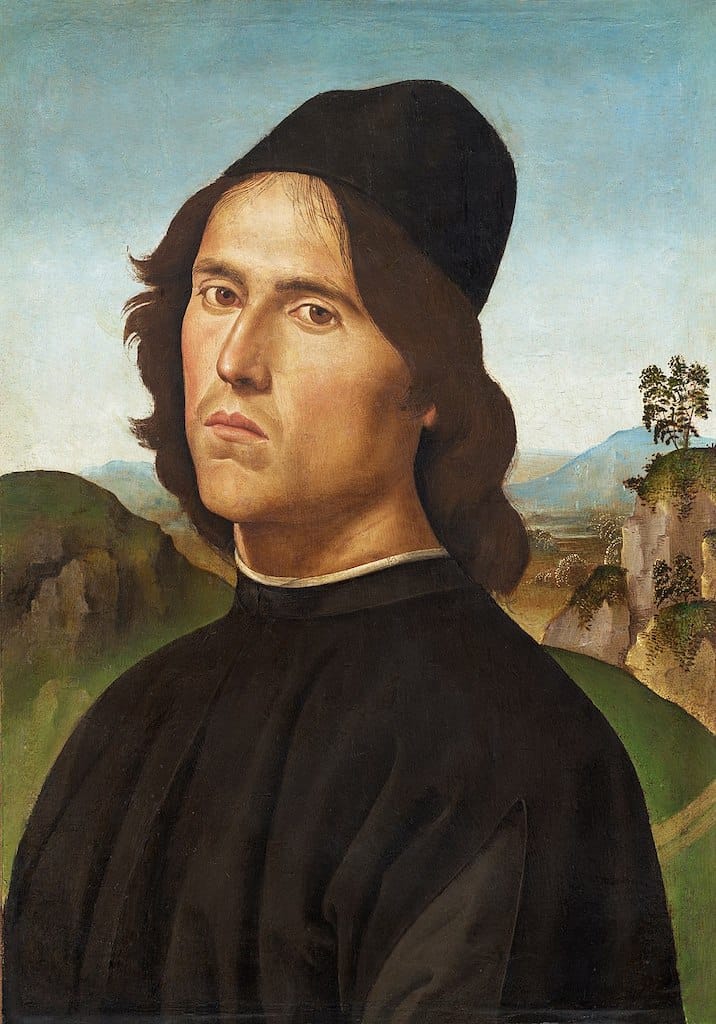

By the fifteenth century, the workshop system had become more sophisticated. The Florentine workshops of Andrea del Verrocchio and, later, Leonardo da Vinci exemplify this evolution. Verrocchio’s studio was celebrated not only for its master’s sculptural prowess but also for training luminaries such as Lorenzo di Credi and Perugino. Young artists would begin by grinding pigments and stretching canvases; with time and aptitude, they would assist in underpainting, execute backgrounds, or even paint entire secondary figures.

Leonardo, who trained under Verrocchio, inherited this model. His own workshop in Milan employed several pupils—among them Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio and Marco d’Oggiono—who undertook commissioned portraits, religious panels and anatomical studies under Leonardo’s supervision. While Leonardo himself would typically execute the principal elements—the central figures, faces and hands—his studio assistants might finish drapery, landscapes or subsidiary details. The final painting, however, bore Leonardo’s name and was sold at his established rate.

Similarly, in Rome, Raphael’s workshop became a hive of activity during the 1510s. At its height, Raphael employed over fifty painters and craftsmen to help realise the vast frescoes of the Vatican’s Stanze and Loggie. Students like Giulio Romano and Perino del Vaga absorbed Raphael’s compositional strategies and stylistic flourishes. Although Raphael touched almost every part of the frescoes’ design, many of the actual brushstrokes were delivered by his assistants. Indeed, certain sections of the Loggia—even today—are known to have been carried out entirely by Giulio Romano based on Raphael’s cartoons (preparatory drawings).

The Scale and Economics of Studio Production

Why did the masters employ so many assistants? The answer lies in demand and finance. As the prestige of an artist grew, so did the volume of commissions—from wealthy patrons, ecclesiastical authorities and civic bodies. A single great master could not possibly complete dozens of altarpieces, portrait series and fresco cycles unaided, particularly when deadlines loomed. Workshops enabled studios to deliver high volumes of work on schedule.

Moreover, the economic model was clear: the master’s name commanded a premium. A painting signed “by Raphael” fetched far more than one by an unknown journeyman, even if stylistically similar. Consequently, the master invested time in designing and overseeing each work, while the bulk of the painting could be delegated. Assistants received modest wages or apprenticed in exchange for training, whereas the master retained the lion’s share of the commission fee.

Case Study: Titian and the Venetian Atelier

In Venice, Titian redefined the studio system towards the end of the sixteenth century. His workshop, based in the Fondamenta dei Greci, was both his residence and production centre. Assistants such as Paris Bordone, Giovanni da Udine and later Palma Giovane received rigorous instruction in Titian’s handling of oil glazes, sumptuous colour harmonies and bold brushwork.

By the 1540s, Titian was producing mythological and religious canvases at an astonishing rate—largely through delegation. He would paint the focal figures—heroes, gods and saints—while assistants rendered backgrounds, architectural elements and drapery. At times, Titian would give a nearly complete underpainting to a trusted pupil to finish in his absence during diplomatic missions or while working on other major commissions.

Titian’s correspondence reveals his trust in his atelier: he wrote to patrons assuring them that even if he could not personally execute every inch of paint, the work would be completed “according to my invention and manner” by “worthy and carefully instructed” hands. Such reassurances highlight the perceived continuity between the master’s creative conception and the studio’s execution.

Connoisseurship and Attribution: The Modern Challenge

The collaborative nature of these studios presents a challenge to modern connoisseurship. How do we distinguish the master’s hand from that of an assistant? Art historians and technical analysts employ infrared reflectography, X‑radiography and pigment analysis to uncover underdrawings, alterations and brushstroke patterns. These scientific techniques help identify sections likely rendered by the master—often in more fluid, confident strokes—versus those by apprentices, whose work can be comparatively cautious or formulaic.

Attribution remains a nuanced debate. Consider “The Madonna of the Goldfinch,” traditionally attributed to Raphael. Recent studies suggest that, while Raphael planned the composition and may have painted the central figures, much of the landscape and peripheral angels were likely the work of his workshop (primarily Giulio Romano and Perino del Vaga). Such findings do not diminish Raphael’s genius; rather, they illuminate the collaborative enterprise that underpinned Renaissance artistry.

Apprenticeship as Artistic Education

Beyond production, the studio system functioned as the principal mode of artistic education. Apprentices learned drawing, anatomy, perspective and colour theory through direct observation and mimicry. They could study antique sculpture in workshops situated near Roman ruins, copy master drawings and attend public dissections to understand human anatomy. This immersive training cultivated not only technical prowess but also stylistic sensibilities aligned with the master’s vision.

Upon completing their term—typically six to eight years—apprentices either set up their own studios or remained as journeymen under the master. Artists such as Parmigianino and Bronzino, once pupils in leading workshops, went on to establish influential schools of their own. Thus, the apprentice system ensured the propagation of stylistic schools—Florentine, Venetian, Roman—and forged networks of artistic lineage.

The Transition to the Modern Era

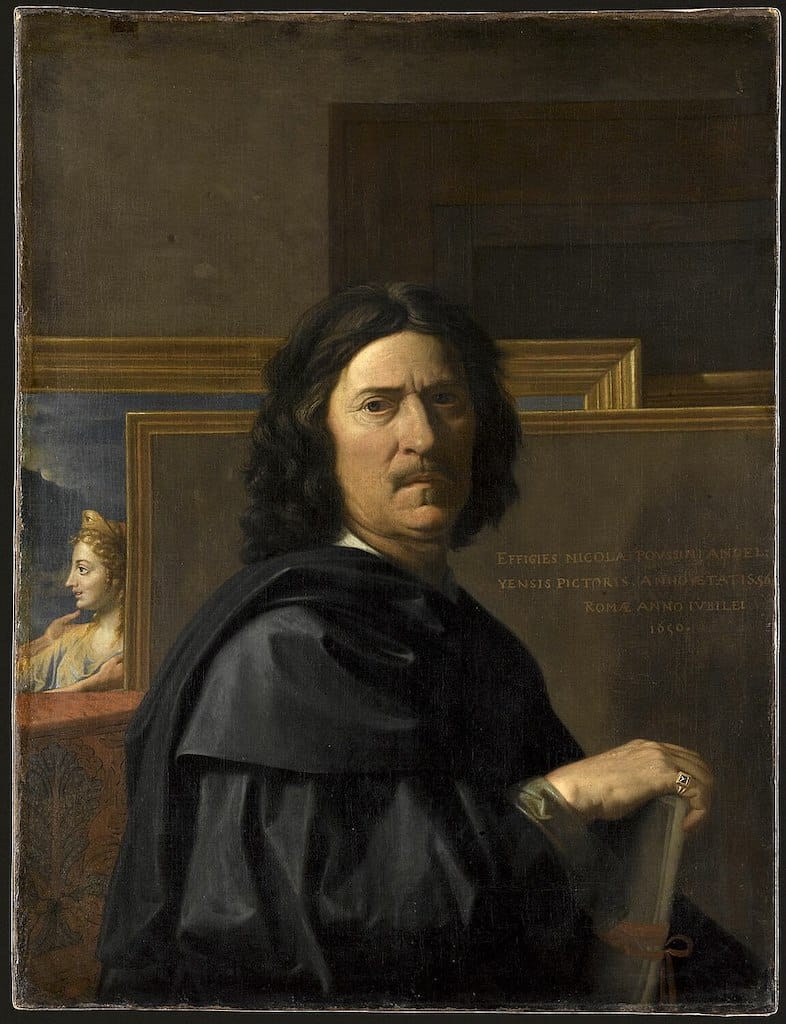

By the seventeenth century, the studio model began to evolve. The rise of academies, such as the Accademia di San Luca in Rome and the French Royal Academy, introduced more formalised instruction, emphasising life drawing from the nude model and theoretical discourse. Nonetheless, many leading painters—Peter Paul Rubens, Sir Anthony van Dyck and Nicolas Poussin—continued to operate workshops where assistants executed elements of large commissions.

The Industrial Revolution and the advent of photography in the nineteenth century further altered artistic production. Mass reproduction techniques, commercial art schools and greater emphasis on individual creativity gradually eroded the traditional apprentice system. However, the core principles—learning through practice and collaboration—persisted in modern art studios and ateliers worldwide.

Reassessing Authorship and Artistic Genius

Understanding the studio apprentice system invites us to reassess conventional notions of authorship. The Old Masters were neither solitary hermits nor mere managers of labour; they were creative directors who combined inventive genius with practical leadership. Their ateliers functioned as both schools and production lines, fostering innovation while meeting the demands of an art market hungry for their names.

When you stand before a Renaissance altarpiece or Baroque canvas today, it is worth remembering the communal effort behind its creation. The master’s vision and the apprentice’s hand were inseparable components of a living tradition. Recognising this interplay enriches our appreciation of the art: every brushstroke, whether by an Old Master or a devoted pupil, contributed to a masterpiece that transcended individual effort.