Was the Mona Lisa Always Famous? The Role of Theft in Creating Legends

Leonardo da Vinci’s 'Mona Lisa' was admired for centuries, but it wasn’t always world-famous. A daring 1911 theft transformed it from a Renaissance portrait into a global icon, proving how scandal can create legends.

Few artworks in the world are as instantly recognisable as Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa. The enigmatic smile, the mysterious landscape, and the subject’s direct gaze have become icons of global culture, reproduced endlessly on mugs, T-shirts, and advertisements. Millions flock to the Louvre each year just to stand before it—sometimes only for seconds—before snapping a photograph.

But here is the intriguing question: was the Mona Lisa always this famous? Or did a strange twist of fate—a theft in 1911—turn it from a celebrated Renaissance portrait into the single most famous painting in the world? The answer requires us to trace the painting’s history, its early reception, and the curious way that scandal and media spectacle can shape artistic legends.

A Work of Admiration, Not Obsession

When Leonardo da Vinci began work on the portrait around 1503, he could hardly have predicted the global fascination it would later inspire. The sitter, widely believed to be Lisa Gherardini, the wife of a wealthy Florentine merchant, was rendered with the master’s unmatched skill in capturing psychological depth and atmospheric illusion.

From the start, artists and connoisseurs admired it. Giorgio Vasari, the 16th-century biographer of Renaissance artists, praised the portrait’s lifelike quality, especially its smile. Raphael, the young genius of the High Renaissance, is thought to have been influenced by it in his own portraits. By the time of Leonardo’s death in 1519, the painting was already seen as a masterpiece.

Yet admiration is not the same as universal fame. For centuries, the painting lived a relatively quiet existence. After Leonardo’s death, it entered the French royal collection and was displayed at the Palace of Fontainebleau and later Versailles. Following the French Revolution, it was placed in the Louvre, where it remained accessible to the public.

Yes, it was admired. Yes, it was studied by artists. But it did not yet hold the singular place in cultural imagination that it does today. To most 19th-century visitors, the Mona Lisa was one among many treasures of the Louvre, jostling for attention alongside works by Raphael, Titian, and Vermeer.

The Pre-Theft Reputation

By the 19th century, the Mona Lisa had gained a reputation among intellectuals and artists as an extraordinary painting. Writers like Théophile Gautier described it in almost mystical terms, emphasising its strange power. Symbolist poets, fascinated by beauty and mystery, treated it as an embodiment of femininity and enigma.

Yet these were elite circles. For the general public, the Mona Lisa was hardly a household name. It did not dominate guidebooks. Tourists did not rush directly to see it. Indeed, when artists made pilgrimages to the Louvre, they were just as likely to sketch Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People or Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa.

In other words, while the Mona Lisa was respected, it was not yet the world’s most famous painting. Its legend was waiting for a catalyst.

The 1911 Theft: A Scandal that Shocked the World

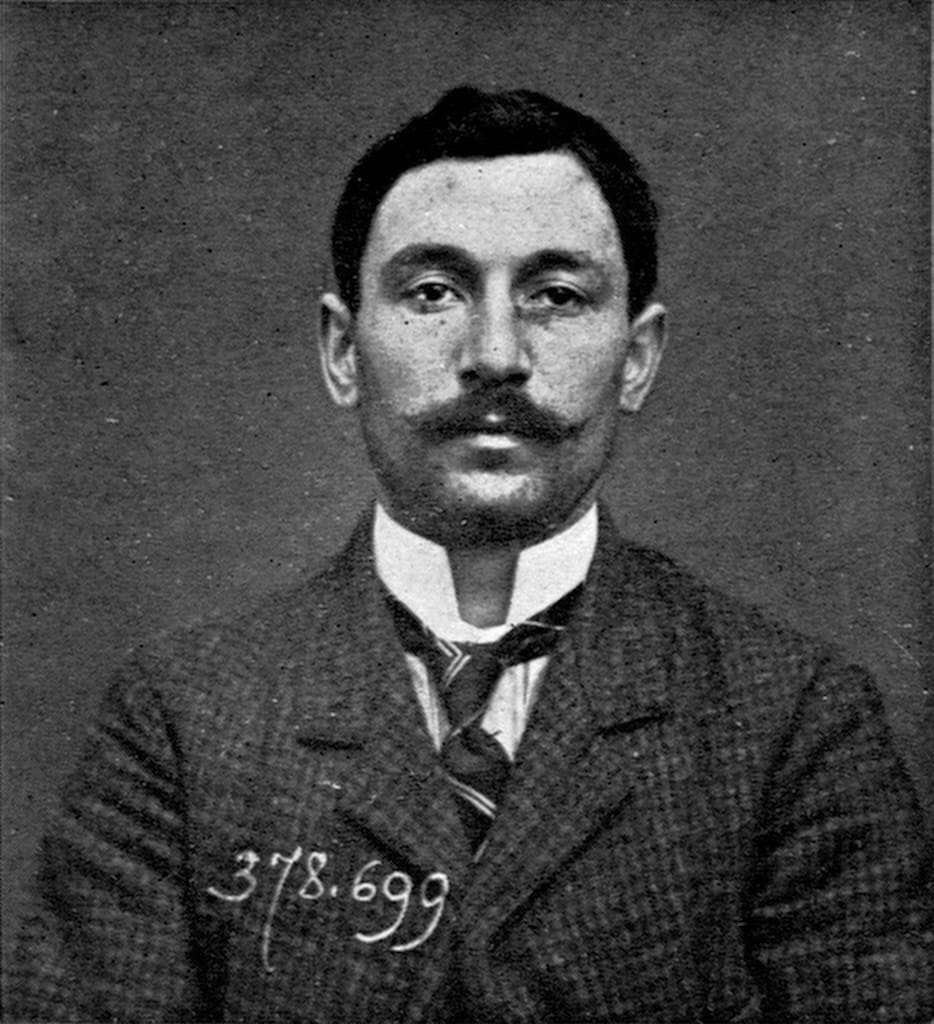

That catalyst arrived on the morning of August 21, 1911. A humble Italian handyman named Vincenzo Peruggia, who had previously worked at the Louvre, managed to steal the painting. Dressed in a white smock similar to the uniforms worn by museum staff, he entered the building, removed the painting from its frame, and walked out with it hidden under his clothing.

The theft was not discovered until hours later. When it was, the news sent shockwaves across France and beyond. Newspapers splashed the story across their front pages. How could the Louvre—the pride of the French Republic—lose one of its treasures?

In the days that followed, the museum was thrown into chaos. Thousands of Parisians queued up not to see the Mona Lisa, but to view the empty space where it had once hung. Suddenly, a painting that had been admired largely by connoisseurs became the subject of widespread public obsession.

The theft turned the Mona Lisa into a news sensation. Suspects ranged from common criminals to avant-garde artists. At one point, even Pablo Picasso was questioned in connection with the crime. The painting’s absence made it more famous than its presence had ever done.

Two Years of Absence

For two years, the painting was missing. During that time, speculation grew. Was it destroyed? Was it hidden in some aristocrat’s private collection? Or had it been spirited away to America?

The media frenzy transformed the Mona Lisa into a symbol of mystery and intrigue. Writers published poems and essays about it. Cartoonists lampooned the theft in satirical illustrations. The more people heard about it, the more they longed to see it.

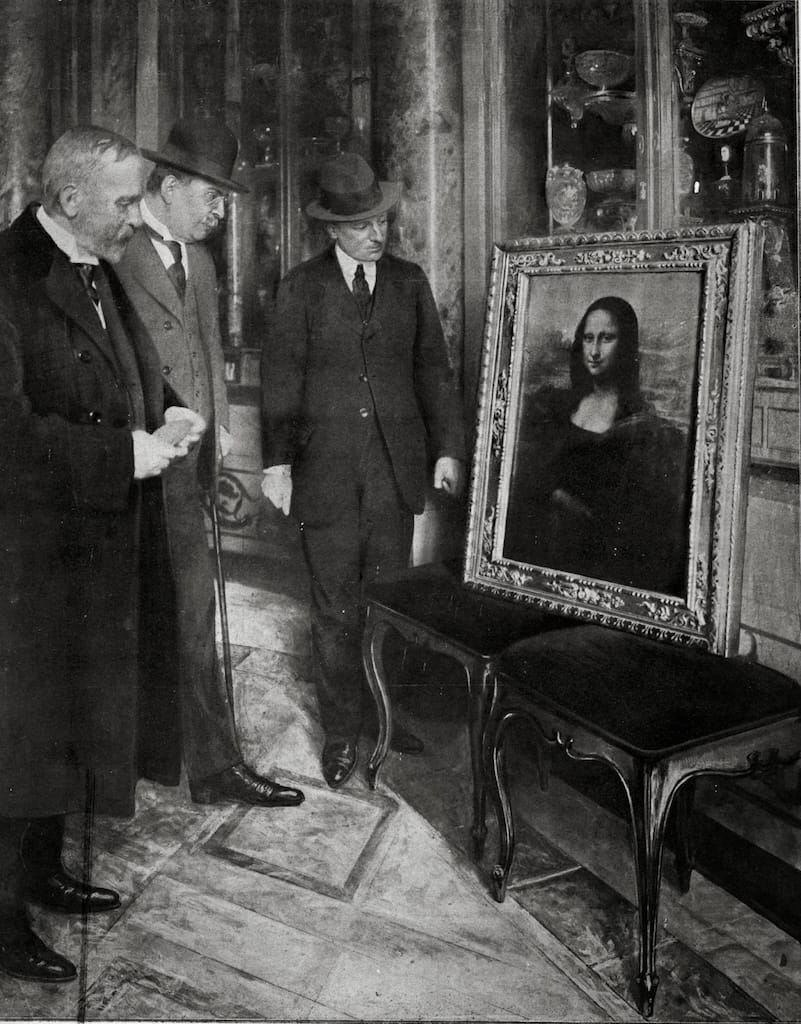

When Peruggia was finally caught in Florence in 1913—having tried to sell the painting to an art dealer—the story reached its dramatic climax. Peruggia claimed he had stolen the painting out of patriotism, believing that the Mona Lisa should be returned to Italy. After a brief trial, he served a short prison sentence. The painting was triumphantly returned to the Louvre, welcomed with near-hysteria by the French public.

Fame Born of Absence

Ironically, it was the Mona Lisa’s absence that made it present everywhere. The theft transformed it from a respected Renaissance masterpiece into a cultural icon. Overnight, it went from being an artwork for specialists to a painting known to the masses.

The incident coincided with the rise of mass media. Newspapers, magazines, and postcards spread the story worldwide. Photographs of the empty frame and reproductions of the painting circulated on an unprecedented scale. The more the public saw these images, the more they associated the Mona Lisa with mystery, scandal, and allure.

This is perhaps the key to its fame: the theft gave it a story. A painting with a story is always more memorable than a painting without one. The Mona Lisa became not just a work of art but a protagonist in a dramatic narrative—stolen, missing, recovered. That narrative continues to fuel its mystique today.

Celebrity Status in the 20th Century

After its recovery, the Mona Lisa never returned to its pre-theft obscurity. Instead, it grew in stature decade after decade. By the mid-20th century, it was firmly established as the world’s most famous painting.

This fame was reinforced through blockbuster exhibitions. In 1963, the painting travelled to the United States, where it was displayed in Washington, D.C., and New York. Crowds queued for hours just to glimpse it. In 1974, it toured Japan and Moscow, drawing similar excitement. Each trip reinforced its aura as a global treasure.

Popular culture also played its part. From Andy Warhol’s silkscreens to countless parodies and advertising campaigns, the Mona Lisa became a shorthand for “art” itself. Its smile was endlessly dissected, psychoanalysed, and mimicked. Scholars debated whether she was smiling at all, or whether the smile was an illusion.

In short, the theft had catapulted it to stardom, and the 20th century ensured it remained there.

Was the Theft the Only Reason?

It would be too simplistic, however, to say that the Mona Lisa owes its fame solely to theft. The painting itself possesses unique qualities that sustain its reputation. Leonardo’s mastery of sfumato, the subtle blending of tones, creates a sense of lifelike presence. The enigmatic expression resists interpretation, inviting endless speculation. The landscape, at once real and dreamlike, enhances the sense of mystery.

In other words, the theft may have made the painting famous, but it is Leonardo’s genius that keeps us fascinated. Had the stolen painting been a lesser work, its notoriety might have faded with time. Instead, the theft directed the spotlight onto a work that could withstand—and even thrive under—intense scrutiny.

The Modern Pilgrimage

Today, millions of visitors to the Louvre make their way through its grand halls to stand before the Mona Lisa. The painting is displayed behind bulletproof glass, protected by barriers, and watched over by guards. The experience can be frustrating: the crowds are thick, and one often sees the painting only from a distance. Yet the pilgrimage continues.

Why? Because seeing the Mona Lisa has become a rite of passage, a cultural must-do. People go not just to admire it, but to participate in its legend. The act of being there, of saying “I saw the Mona Lisa,” connects them to the long chain of stories surrounding it—from Leonardo’s studio to the halls of Versailles, from the theft of 1911 to its global tours.

The painting has moved beyond art history into the realm of myth.

The Making of a Legend

So, was the Mona Lisa always famous? The answer is no. For centuries, it was respected but not dominant. Its rise to superstardom came not from Leonardo alone, nor from Renaissance connoisseurs, but from an unexpected thief and the world’s fascination with scandal.

The theft of 1911 did not create the Mona Lisa’s greatness—that was Leonardo’s achievement. But it did create the conditions for its myth, transforming it into the most recognisable painting in the world. Today, when we gaze at that smile, we are not just seeing a portrait of a Florentine woman. We are witnessing a legend—one born of art, mystery, and the strange power of a story.