Understanding Tibetan Art: A Comprehensive Guide

Explore the evolution of Tibetan art—from Bon origins and Himalayan murals to Gelug masterpieces and contemporary diaspora expressions—delving into techniques, symbolism, regional styles, conservation challenges, and modern innovations that illuminate this rich, transcendent visual tradition.

Tibetan art, in its myriad forms, stands as one of the world’s most distinctive and spiritually resonant visual traditions. Rooted in the Himalayan plateau’s unique confluence of indigenous Bon practices and the later influx of Indian and Chinese Buddhist influences, Tibetan artistic expression encompasses painting, sculpture, metalwork, textiles, and ritual objects. More than mere decoration, each work functions as a vessel for religious doctrine, meditation aid and the embodiment of enlightened principles. This guide will introduce the key historical phases, technical media, iconographic conventions, stylistic schools and contemporary developments that together form the rich tapestry of Tibetan art.

Historical Overview

Indigenous origins and pre-Buddhist Bon art

Prior to the arrival of Buddhism in the seventh century CE, the Himalayan region was characterised by the Bon religion. Bon artisans produced rudimentary thangka‐like banners, sculptural forms in wood and stone, and ritual objects—such as the phurba (ritual dagger)—primarily for shamanic ceremonies. Although much of this early material culture has been lost or assimilated, its emphasis on animistic symbolism and natural forces underpins later Tibetan aesthetics.

The first Buddhist wave (7th–11th centuries)

In 641 CE, King Songtsen Gampo’s marriage alliances with Nepal and Tang China introduced Buddhism to Tibet. Monasteries such as Samye (founded c. 775 CE) became centres for translation and artistic exchange. Indian pandits and Nepalese artisans taught the painting of narrative murals and the casting of gilt‐bronze Buddhist figures. Early mural programmes at Tabo in Ladakh (c. 996 CE) and Alchi in Western Tibet (c. 1200 CE) illustrate a vibrant synthesis of Kashmiri‐Pakistani line work, Nepalese iconographic precision and indigenous colour palettes.

The second diffusion and Sakya‐Kagyu renaissance (11th–14th centuries)

The second great wave of Indian Buddhist masters, notably Atīśa Dīpaṅkara Śrījñāna (982–1054), revitalised monastic discipline and artistic patronage. The Sakya and later the Kagyu schools commissioned increasingly refined sculpture and painted thankas. The emergence of the ‘Newari style’, named after Kathmandu Valley’s artisans, saw an explosion of metal‐gilded Buddhas and enlightened masters, characterised by delicate facial modelling, intricate jewellery and sumptuous lotus‐petal bases.

The Gelug period and later developments (15th–19th centuries)

With Je Tsongkhapa’s founding of the Gelug school in the 15th century, Tibetan art attained new heights of standardisation and technical mastery. The University‐monasteries of Ganden, Drepung and Sera in Lhasa sponsored workshops that produced colossal copper‐alloy Buddha statues—some reaching over 12 metres—and monumental mandala murals in assembly halls. The decorative style became more austere, emphasising harmonious proportions and restrained colour schemes to mirror the Gelug emphasis on monastic discipline and scholarly purity.

The modern era and diaspora (20th century to present)

The Chinese takeover of Tibet (1950s) and subsequent Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of countless monasteries and artworks. Surviving masters and refugees in India, Nepal, Bhutan and the West established new studios, adapting traditional techniques for global markets. Today’s Tibetan art includes contemporary painting that fuses abstraction with thangka conventions, as well as digital reproductions, jewellery and fashion, extending the tradition beyond its Himalayan origins.

Media and Techniques

Thangka painting

Perhaps the most emblematic form of Tibetan art, the thangka is a portable, scroll‐mounted painting rendered on cotton or silk. Artists begin by stretching and priming the cloth with a mixture of chalk and animal glue (“gesso”), then adhere a geometric grid to ensure iconographic accuracy. Mineral and vegetable pigments—indigo, vermilion, malachite, cinnabar—are ground with water and animal glue to yield saturated hues. Gold leaf and powdered gold are applied for highlights. The painting process follows precise iconometric prescriptions: measurements between eyes, torso length and lotus seat dimensions are all specified in sacred texts.

Sculpture and metalwork

Tibetan sculptors work in a variety of materials—wood, clay, stone, copper, brass, bronze and precious metals. Lost‐wax casting (“cire perdue”) is employed for small‐ to medium‐sized bronzes: a wax model is covered in clay, fired to melt out the wax, and then molten metal is poured into the cavity. After cooling, the outer clay shell is broken away and the metal figure is chased, polished and gilded. Larger statues are often built around wood cores with outer layers of clay or metals. Intricate repoussé and chasing work, fine inlay of turquoise and coral, and delicate openwork embellishments attest to the artisan’s virtuosity.

Textile arts and ritual objects

Tibetan carpets, ritual banners (thod pa), ceremonial hats and monastic robes (kāṣāya) incorporate weaving, embroidery, appliqué and brocade. The weaving of silk brocades for thangka borders or altar textiles often uses Indian Kani techniques, while embroidery utilises silk floss for raised, vibrant motifs. Ritual implements—vajra, bell (drilbu), water offering bowls—are cast, then finely engraved and inlaid, each bearing mantra inscriptions and symbolic iconography.

Iconography and Symbolism

The cosmological framework

Tibetan art reflects the Buddhist universe: the Three Jewels (Buddha, Dharma, Saṅgha), the Six Realms of Samsāra, and the mandala of the Five Buddhas (Vairocana, Akṣobhya, Ratnasambhava, Amitābha, Amoghasiddhi). Each deity is depicted with specific hand gestures (mudrā), attributes (vāhana, lotus, bell, vajra) and colour associations, serving as a visual aid for meditation on their enlightened qualities.

Narrative cycles

Lives of the Buddha, the Eight Great Bodhisattvas, Indian Mahāsiddhas and Tibetan lamas (e.g. Milarepa, Tsongkhapa) are depicted in narrative panels, often surrounding a central deity. These didactic paintings combine scenes of birth, enlightenment, miracles, renunciation and instruction, reinforcing moral lessons and lineage continuity.

Mandalas and ritual diagrams

Mandalas, whether two‐dimensional paintings or three‐dimensional replications in sand, represent the palace of a deity. They serve as the spatial blueprint for tantric initiations. A mandala’s concentric circles, lotus petals and square palaces correspond to inner visionary realms. The painstaking creation—and ritual destruction—of sand mandalas demonstrates impermanence (anitya) and compassion.

Stylistic Schools and Regional Variations

Lhasa / Central Tibet

Art from Lhasa monastic centres tends towards formal rigour and refined, pared‐down palettes—soft blues, whites and muted reds. Figures are stately, faces serene, with smooth modelling and emphasised symmetry.

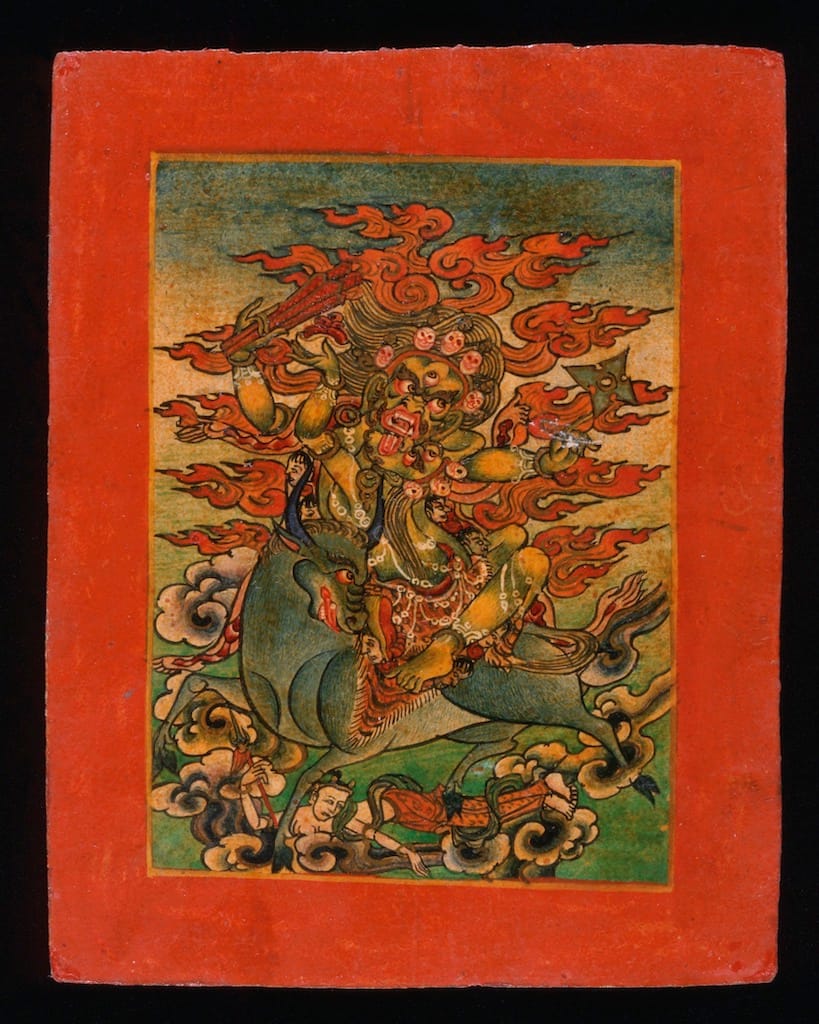

Kham and Amdo (Eastern Tibet)

In the rugged eastern provinces, local materials and nomadic patronage yield bolder pigments, dynamic compositions and a freer approach to line. Deities may be larger‐than‐life and imbued with fierce vitality, reflecting the region’s warrior ethos.

Himalayan borderlands (Nepalese and Bhutanese influences)

Newari artisans based in Nepal have long served Tibetan courts, infusing thangkas with elaborate foliage scrolls, jewel‐like colouration and finely detailed ornament. Bhutanese art shares many conventions but favours a more naïve aesthetic, with simpler backgrounds and emphasis on narrative clarity.

Collecting, Conservation and Ethical Considerations

Authentication and dating

Determining age and workshop origin involves studying pigment composition (e.g. the presence of Prussian blue indicates post‐1704 manufacture), stylistic idiosyncrasies, colophons and inscriptions. Experts examine support materials, mounting techniques and iconographic details to authenticate works.

Conservation challenges

Organic materials—cotton, silk, animal glue—are vulnerable to light, humidity and pests. Conservation specialists employ reversible consolidation methods, deacidification, insecticide treatments and controlled display conditions to preserve artworks’ integrity.

Ethical collecting

Collectors should verify provenance and ensure that objects were not illicitly removed from monasteries or private collections. International treaties (e.g. the 1970 UNESCO Convention) and local laws must be respected. Engaging with Tibetan communities, galleries and monasteries that benefit from sales can support cultural continuity.

Contemporary Tibetan Art

Innovation within tradition

Young Tibetan artists—such as Tenzing Rigdol and Gonkar Gyatso—reconcile traditional thangka techniques with contemporary themes: political commentary, diaspora identity and environmental concerns. Works may utilise acrylics, canvas or mixed media while retaining mandala layouts and deity iconography.

International exhibitions and cross‐cultural dialogues

Museums in New York, London and Kathmandu regularly host exhibitions of historical and contemporary Tibetan art, fostering scholarly research and public awareness. Collaborative residencies bring Tibetan artists into dialogue with Western peers, resulting in hybrid forms and new audiences.

Digital preservation and reproduction

High-resolution photography, 3D scanning, and virtual reality reconstructions are expanding access to monastic mural programs and rare Tibetan sculptures. Digital initiatives such as Himalayan Art Resources, the Buddhist Digital Resource Center (BDRC), and the Tibetan and Himalayan Library (THL) collectively catalogue tens of thousands of works. These platforms not only support scholarly research but also play a vital role in safeguarding endangered sites and preserving Tibetan cultural heritage in digital form.

Conclusion

Tibetan art remains a living tradition, at once deeply rooted in millennia‐old spiritual practices and vibrantly engaged with the modern world. Its forms—thangka painting, bronze sculpture, textile works and ritual implements—function as pedagogical tools, meditation supports and aesthetic expressions of an enduring quest for enlightenment. By appreciating the historical evolution, technical mastery, iconographic precision and contemporary adaptations of Tibetan art, one gains not only an understanding of its visual splendour but also a window into the profound philosophical and cultural currents that continue to shape the Himalayan peoples.