Understanding Lighting: Natural vs. Artificial Light in Photography

Lighting shapes every photograph. This article explores the aesthetic and technical differences between natural and artificial light, examining mood, control, authenticity and creative intention across genres from portraiture to landscape and commercial photography.

Photography is, at its core, the art of shaping light. The word itself derives from the Greek for “drawing with light”, and every image, whether made on a smartphone or a medium format camera, is the result of decisions about illumination. For photographers working across genres, from portraiture and landscape to still life and documentary, the choice between natural and artificial light is not merely technical. It is aesthetic, emotional and often philosophical.

Understanding how these two sources of light behave, and how they influence mood, texture and narrative, is central to developing a distinctive photographic voice.

What Do We Mean by Natural Light?

Natural light refers primarily to sunlight, whether direct or diffused, and to ambient light that exists without the intervention of man-made sources. This includes the changing light of dawn and dusk, overcast skies, window light, reflected light bouncing off walls or pavements, and even moonlight.

Natural light is dynamic. It shifts in intensity, colour temperature and direction throughout the day. The “golden hour” shortly after sunrise or before sunset offers warm, soft illumination with long shadows. Midday light, by contrast, is cooler and harsher, often creating strong contrasts and deep shadows. Overcast conditions produce an even, flattering light that reduces contrast and softens skin tones.

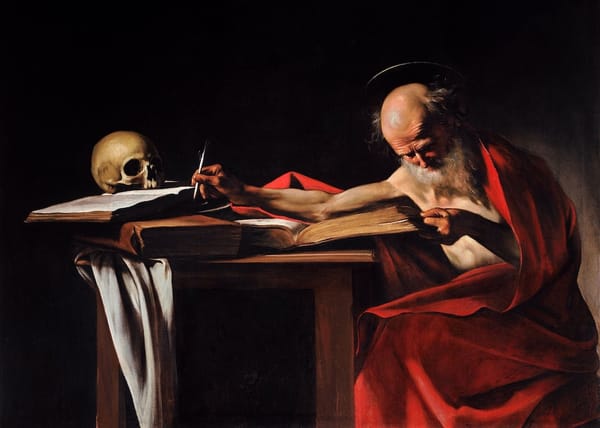

For many photographers, natural light offers authenticity. It situates the subject within a real environment and carries the atmosphere of a particular moment. In landscape photography, for example, the drama of storm clouds or the glow of evening sun is inseparable from the story of the place. In portraiture, window light can create intimacy and subtle modelling on the face without the overt presence of studio equipment.

However, natural light is unpredictable. It cannot be switched on or off. Clouds move, the sun sets, and interior spaces may not provide sufficient illumination. Working with natural light requires patience, observation and flexibility. It demands that the photographer adapt to what is available rather than impose a fixed lighting design.

The Qualities of Artificial Light

Artificial light encompasses all man-made sources, including studio strobes, continuous LED panels, tungsten lamps, flashguns and practical lights within a scene. Unlike natural light, artificial light is controllable. Its intensity, direction, colour temperature and diffusion can be adjusted to suit the photographer’s intention.

In a studio setting, artificial lighting allows for precision. A key light can be positioned to sculpt facial features, a fill light can soften shadows, and a backlight can separate the subject from the background. Modifiers such as softboxes, reflectors, grids and barn doors enable further refinement. The photographer is not at the mercy of the weather or the time of day.

Artificial light is also essential in genres where consistency matters. Commercial photography, fashion editorials and product shoots often require repeatable results. When photographing a watch or a bottle of perfume, for instance, highlights and reflections must be carefully controlled to reveal texture and form. Artificial lighting provides the repeatability and control that clients expect.

Yet artificial light can appear contrived if poorly handled. Hard flash without diffusion may produce unflattering shadows and specular highlights. Colour mismatches between different light sources can result in unnatural skin tones. The challenge lies in using artificial light in a way that feels intentional rather than mechanical.

Mood and Atmosphere

One of the most significant differences between natural and artificial light lies in their emotional impact.

Natural light often carries a sense of realism and spontaneity. A candid street photograph taken in late afternoon light may evoke warmth and nostalgia. A misty morning scene can feel contemplative or melancholic. Because viewers are accustomed to seeing the world in natural light, such images can feel immediate and truthful.

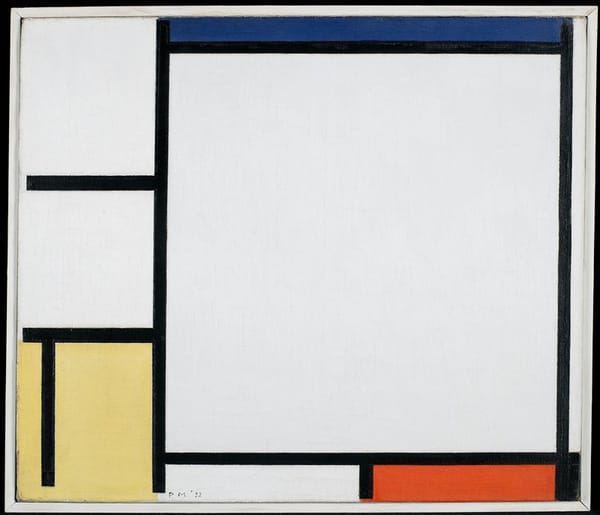

Artificial light, on the other hand, can be dramatic and theatrical. High contrast studio lighting may create a bold, sculptural portrait. Coloured gels can transform a simple scene into something cinematic or surreal. In fine art photography, artificial light can be used to construct entirely imagined worlds, where reality is secondary to concept.

Neither approach is inherently superior. The choice depends on the story the photographer wishes to tell. A documentary project about daily life may benefit from the unobtrusive presence of natural light, while a conceptual portrait might demand the deliberatei accuracy of studio control.

Technical Considerations

From a technical perspective, natural and artificial light present distinct challenges and opportunities.

Natural light changes continuously. Photographers must monitor shutter speed, aperture and ISO as conditions shift. Shooting indoors with window light may require higher ISO settings, which can introduce noise. Outdoors, harsh sunlight may necessitate the use of reflectors or diffusers to manage contrast.

Artificial light introduces additional variables. Flash photography requires an understanding of sync speed, flash power and light ratios. Continuous lighting may generate heat or require higher power consumption. Balancing artificial light with ambient light can be complex, particularly when colour temperatures differ. For example, mixing daylight with tungsten bulbs may produce areas of blue and orange within the same frame.

However, artificial light offers solutions to technical limitations. In low light environments, a well placed flash can freeze motion and ensure sharpness. In high contrast scenes, adding fill light can preserve detail in shadows without overexposing highlights.

In both cases, mastery depends on understanding how light interacts with surfaces. Hard light emphasises texture and detail, revealing wrinkles, fabric weave or architectural lines. Soft light smooths surfaces and reduces imperfections. The distance between the light source and the subject also affects the quality of illumination, with closer light generally appearing softer relative to the subject.

Blurring the Boundaries

In contemporary photography, the distinction between natural and artificial light is often less clear than it first appears. Many photographers blend the two. A portrait might be lit primarily by window light, with a subtle reflector or LED panel used to lift shadows. An interior architectural photograph may rely on ambient daylight supplemented by discreet flash to balance exposure.

This hybrid approach allows for greater flexibility. It combines the authenticity of natural light with the control of artificial illumination. The aim is often to enhance rather than replace what is already present.

Modern cameras and post processing software have also changed the conversation. Higher ISO performance makes it possible to work in lower light conditions without artificial sources. Conversely, advanced lighting systems with adjustable colour temperatures make artificial light more adaptable to natural environments.

Choosing the Right Approach

When deciding between natural and artificial light, photographers might consider several questions.

What is the narrative intent of the image? Is the goal to capture a fleeting moment or to construct a carefully designed composition? What are the practical constraints of the location? Is there sufficient ambient light, or does the subject require additional illumination? How much control is necessary?

For emerging photographers, working with natural light can be an excellent way to develop observational skills. Learning to see how light falls on faces, walls and landscapes at different times of day builds a foundational understanding of form and shadow.

At the same time, experimenting with artificial light encourages technical discipline. Setting up even a simple two light arrangement teaches lessons about direction, contrast and balance that apply across all forms of photography. The most accomplished photographers are fluent in both languages. They recognise that light is not merely a technical requirement but the primary expressive tool of the medium.