The Tragic Life of Modigliani: Myth or Marketing?

Amedeo Modigliani’s image as a doomed bohemian has fascinated generations—but how much of his so-called tragic life is rooted in fact, and how much has been cleverly spun by the art market?

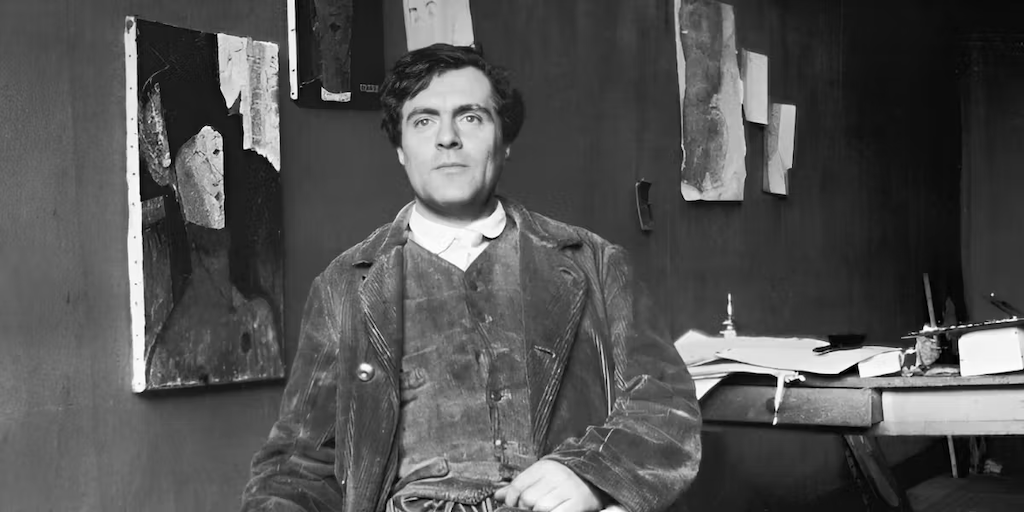

The Italian artist Amedeo Modigliani (1884–1920) is often remembered less for his paintings than for his life—or, more precisely, for the myth of his life. He is cast as the archetypal tortured genius: handsome, penniless, addicted to alcohol and drugs, spurned by critics, and dead at 35 from tuberculosis. His art, particularly the elongated nudes and portraits, is now instantly recognisable and fetches staggering sums at auctions. But behind this popular narrative lies a question that has haunted art historians and critics for decades: how much of Modigliani’s story is true, and how much has been romanticised, exaggerated, or outright fabricated in the service of posthumous fame and market value?

The Bohemian Mythos

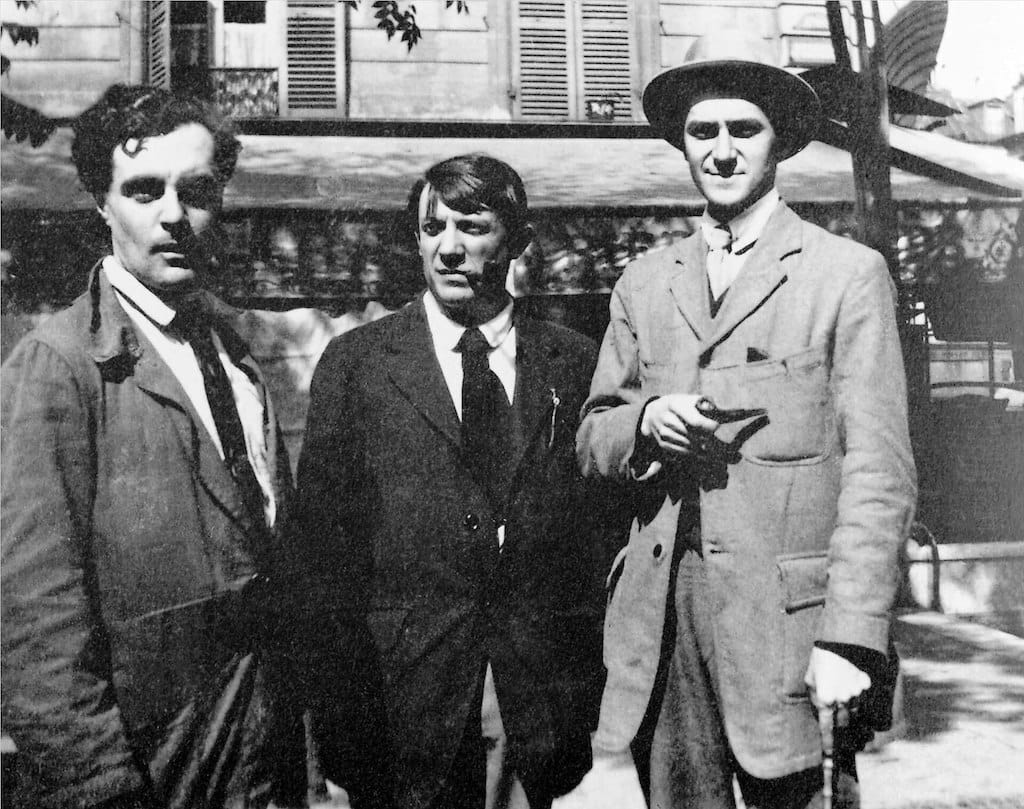

Modigliani's life in early 20th-century Paris, particularly in the artistic hotbed of Montparnasse, fits neatly into the romantic archetype of the suffering artist. He was surrounded by contemporaries like Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuși, and Chaim Soutine, who formed part of the so-called École de Paris. These artists, mostly émigrés, lived frugal, intense lives, constantly struggling for recognition.

Modigliani stood out among them. He was tall, dashing, and always impeccably dressed—even when living in near-destitution. Tales of his public drunkenness, fiery temperament, and doomed love affair with Jeanne Hébuterne have become part of his artistic identity. His reputation as a libertine—dashing through cafés in a drunken haze, declaiming Dante while naked, seducing models, destroying his own work in fits of rage—has been repeated so often it has hardened into legend.

Yet few of these anecdotes can be corroborated. They come largely from friends' memoirs, letters, and secondhand reports, often written years after his death. And while Modigliani certainly suffered physically (he had tuberculosis and possibly syphilis) and struggled financially, the extent to which he was entirely unappreciated in his lifetime is questionable.

Fact vs Fabrication

Recent scholarship has revealed that Modigliani was not quite as neglected as legend suggests. He had several patrons, including Paul Alexandre, Léopold Zborowski, and Jonas Netter, who provided him with studio space, materials, and money. His work was included in group exhibitions, and he had a solo show during his lifetime—though infamously shut down by police due to the supposed indecency of his nudes.

Moreover, some of the more dramatic stories—such as the claim that Modigliani died in a squalid garret, alone and forgotten—do not withstand scrutiny. In reality, he died in hospital, surrounded by friends. The real tragedy perhaps lies more in the death of his pregnant partner Jeanne Hébuterne, who, in despair, took her own life two days after Modigliani’s death. This act lent a fatalistic, operatic tone to the myth.

One might ask: who benefits from the tragedy?

The Market for Melancholy

After Modigliani’s death in 1920, a surge of interest in his work followed almost immediately. Within a few years, dealers began to reposition him as a martyr of modern art—a misunderstood genius, unrecognised in his time. This narrative, while not unique to Modigliani, proved especially potent.

In the decades that followed, the myth was cemented by biographers and art dealers, particularly those with a stake in the value of his works. His portraits and nudes—once considered vulgar or derivative—began to rise in price. By the post-war period, he was firmly established as one of the modernist greats. The market’s love affair with Modigliani reached its peak in 2015, when Nu couché (1917–18) sold at Christie’s for $170.4 million, making it one of the most expensive paintings ever sold at auction.

This meteoric rise has prompted some critics to question whether the image of Modigliani as a tragic hero has been deliberately cultivated to enhance the value of his oeuvre. After all, the tragic artist trope appeals to collectors’ romanticism, allowing them to see themselves not merely as buyers of paintings, but as rescuers of lost genius.

Artistic Identity and Authenticity

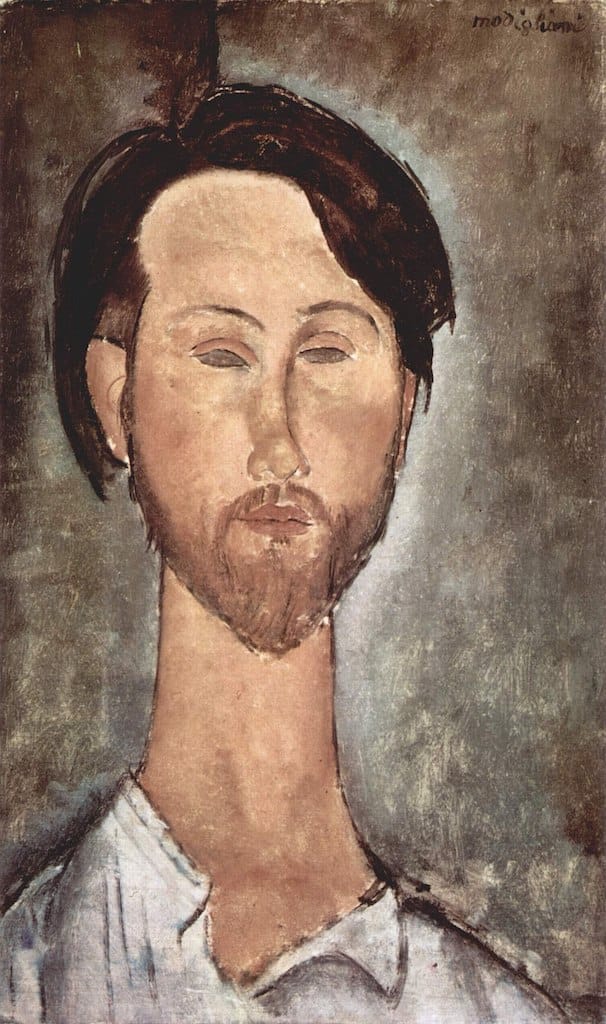

Ironically, Modigliani himself was intensely aware of the role of image in art. While he never achieved fame in his lifetime, he understood the necessity of persona. He cultivated a distinctive aesthetic, both in his painting and in his public self. His signature elongated faces and almond eyes drew on African masks, Egyptian sculpture, and early Italian painting. These works were not created in a vacuum of poverty and desperation—they were the product of careful, intentional artistry.

Indeed, Modigliani’s notebooks, letters, and preparatory drawings show a thoughtful and rigorous approach. His work displays remarkable consistency of style and an acute sensitivity to form. The frequent comparison to El Greco or Botticelli, far from accidental, hints at his desire to place himself within an idealistic lineage. His choice of mediums—especially his early sculpture—demonstrates a formal engagement with material and technique that belies the "bohemian layabout" stereotype.

To reduce his biography to a tale of drugs, drink and doom does a disservice to the depth and intelligence of his art.

The Role of Dealers and Forgers

Adding further complexity to the Modigliani mythology is the long shadow of forgeries. Due to the high demand and relative simplicity of his style, Modigliani's paintings have been widely faked. Entire exhibitions have been pulled after multiple works were revealed to be forgeries, most notably the 2017 show in Genoa, where 21 out of 30 Modigliani paintings were declared counterfeit.

In this environment, stories of the artist’s turbulent life often distract from rigorous scholarship. A romantic narrative can obscure inconsistencies in provenance or attribution. The myth becomes a shield, encouraging emotional rather than critical responses.

Moreover, several of Modigliani’s early dealers had strong incentives to both sell his work and enhance its backstory. While this is not unique in the art world, in Modigliani’s case, the line between biography and marketing becomes especially blurred.

The Allure of the Tragic Genius

Why, then, does the myth endure?

Part of the answer lies in our cultural fascination with the "tortured artist" archetype. From Van Gogh to Sylvia Plath, we are drawn to creators who suffer for their art. It reassures us that genius cannot be manufactured, that it must be born of fire. In Modigliani’s case, this narrative is doubly seductive: the beauty of his work juxtaposed with the ugliness of his life creates a compelling contrast.

But this attraction carries risks. It perpetuates the notion that suffering is a prerequisite for artistic greatness, and may even lead to the fetishisation of pain. It also overlooks the very real labour, training, and intellect involved in creating art.

Conclusion

Modigliani’s life certainly contained elements of tragedy—ill health, financial struggle, and early death. But the idea of a completely unrecognised, destitute genius has been exaggerated, if not outright constructed. While his myth has helped propel his work to global renown, it has also obscured the nuance and complexity of both the man and the artist.

To truly appreciate Modigliani, we must move beyond the smoke and mirrors of romanticism and engage with his paintings and drawings on their own terms. His legacy should rest not only on a tragic tale, but on his enduring artistic vision—one of elegance, simplicity, and deep psychological insight.