The Sketchbook as a Pedagogical Tool

The sketchbook is more than a collection of drawings. It is a powerful pedagogical tool that cultivates observation, reflection, experimentation and critical thinking, shaping students into thoughtful, resilient and visually literate artists.

In studios, classrooms and museums across the world, the sketchbook remains one of the most quietly powerful instruments in an artist’s formation. Modest in appearance and often private in nature, it occupies a space somewhere between diary, laboratory and rehearsal room. For educators, the sketchbook is far more than a repository of drawings. It is a pedagogical tool that nurtures observation, critical thinking, reflection and risk-taking. Properly integrated into teaching, it can transform the way students learn to see, think and create.

A Historical Lineage of Process

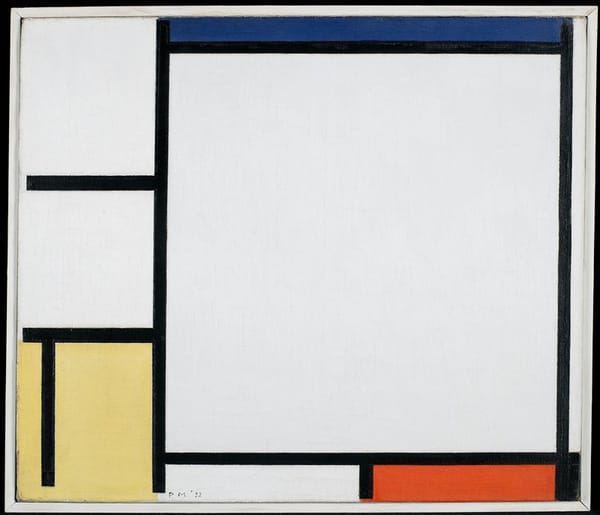

The sketchbook has long been central to artistic practice. The notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci, filled with anatomical studies, engineering designs and speculative diagrams, reveal a mind thinking on paper. Similarly, the small, portable studies of J. M. W. Turner, created during his travels, capture fleeting atmospheres and compositional experiments that would later inform major canvases. In the twentieth century, artists such as Pablo Picasso used sketchbooks to test forms and fragment figures before resolving them into finished works.

These examples remind us that art does not emerge fully formed. It develops through iteration, revision and doubt. When students encounter the sketchbooks of such artists, they begin to understand that uncertainty and experimentation are not signs of failure but integral aspects of creative practice. The pedagogical value lies not only in the artefacts themselves but in the attitudes they model.

Observation and the Discipline of Looking

One of the primary educational functions of the sketchbook is to cultivate sustained observation. In an age dominated by digital images and rapid consumption, students often glance rather than look. The act of drawing from life demands slowness. It requires attention to proportion, light, texture and spatial relationships.

When teachers assign regular observational studies in a sketchbook, they are not merely training manual skill. They are fostering habits of attentiveness. A student who repeatedly sketches the same object across several pages begins to notice subtle shifts in perspective and shadow. This repetition deepens visual literacy. Over time, the sketchbook becomes a record of seeing more clearly.

Moreover, observational sketching can extend beyond traditional still life or figure drawing. Students might document architectural details in their neighbourhood, the gestures of commuters on a train, or the changing quality of light in a particular space. Such exercises connect art education to lived experience, reinforcing the idea that the world itself is a primary classroom.

Process Over Product

Contemporary education often privileges outcomes. Grades, exhibitions and portfolios can inadvertently shift focus towards polished results. The sketchbook resists this tendency by foregrounding process. It is a space where unfinished thoughts are not only permitted but encouraged.

In pedagogical terms, this emphasis on process aligns with formative assessment. Teachers can review sketchbooks periodically, offering feedback that supports development rather than judgement. Comments might address compositional decisions, conceptual clarity or the exploration of materials. The aim is to guide thinking, not to reward surface polish.

Importantly, when students understand that the sketchbook is a low stakes environment, they are more likely to experiment. They may attempt unfamiliar techniques, combine disparate influences or pursue idiosyncratic ideas. This willingness to take risks is essential for genuine artistic growth. By contrast, a system focused solely on finished pieces can produce cautious, derivative work.

Reflection and Metacognition

The sketchbook is not confined to drawing. It can incorporate written reflections, questions, mind maps and research notes. Encouraging students to annotate their visual studies transforms the book into a site of metacognition, where they examine their own thinking.

For example, after completing a series of compositional sketches, a student might write about what feels successful and what remains unresolved. They may note influences from artists they admire, or articulate the conceptual thread connecting disparate pages. This reflective practice strengthens critical awareness.

From a pedagogical perspective, such reflection bridges studio practice and art history or theory. When students refer to artists like Paul Klee or Frida Kahlo within their sketchbooks, they begin to situate their work within broader traditions. The sketchbook becomes a dialogue between personal exploration and cultural context.

Teachers can scaffold this process through prompts. Questions such as, What are you trying to communicate here? or How does this study relate to your larger theme? encourage students to articulate intention. Over time, they learn to pose such questions independently.

Interdisciplinary Connections

The pedagogical potential of the sketchbook extends beyond the visual arts. In design education, it supports iterative prototyping. In architecture, it facilitates spatial thinking. In music or theatre, a similar notebook can house conceptual sketches, staging diagrams or notated ideas.

For younger students in particular, the sketchbook can serve as a bridge between subjects. A science lesson on plant structures might lead to detailed botanical drawings. A history unit on industrialisation could inspire studies of machinery or urban landscapes. By integrating visual documentation into other disciplines, educators reinforce the interconnectedness of knowledge.

This interdisciplinary approach also reflects contemporary artistic practice, where boundaries between mediums are increasingly fluid. Encouraging students to collage printed text, incorporate photography or experiment with mixed media within their sketchbooks acknowledges this reality. The book becomes a hybrid space, responsive to multiple influences.

Building Confidence and Ownership

A sketchbook is often intensely personal. Unlike a public exhibition, it is not primarily designed for display. This privacy can foster confidence. Students who may feel intimidated by presenting finished work sometimes find greater freedom in a book that belongs to them.

From a pedagogical standpoint, granting ownership is crucial. When students select their own sketchbooks, customise covers or organise pages according to personal logic, they invest emotionally in the process. The book becomes an extension of identity.

However, educators must balance ownership with structure. Clear expectations about regular use, thematic coherence or documentation of research ensure that the sketchbook remains purposeful. Within that framework, autonomy can flourish.

Assessment and Documentation

The sketchbook also functions as a record of development over time. Flipping through earlier pages, students can witness their own progress. This longitudinal perspective is particularly valuable in secondary and higher education, where portfolio preparation is essential.

For teachers, the sketchbook offers insight into how a student approaches problems. Does the student generate multiple compositional options before settling on one? Do they research visual references? Do they revisit earlier ideas and refine them? Such evidence supports more nuanced assessment than a single finished piece can provide.

In formal qualifications, where process documentation is often required, the sketchbook becomes indispensable. It demonstrates conceptual evolution, technical experimentation and engagement with context. Yet even outside examination systems, its documentary function enriches learning.

Digital Versus Analogue

In recent years, digital tablets and applications have expanded the notion of the sketchbook. Many students now draw directly on screens, layering images and manipulating colour with ease. While digital tools offer undeniable advantages, the pedagogical principles remain consistent.

An analogue sketchbook fosters tactile engagement. The resistance of paper, the unpredictability of ink and the permanence of marks contribute to a specific kind of learning. Mistakes cannot be undone with a simple command. They must be incorporated or reworked.

Digital sketchbooks, on the other hand, encourage experimentation with scale, duplication and transformation. They may be particularly suited to animation, graphic design or multimedia projects. Rather than framing the debate as a binary choice, educators can invite students to consider how each medium shapes thinking.

The essential question is not whether the sketchbook is paper based or digital, but whether it supports sustained inquiry. A device used only for quick, disposable sketches may not fulfil its pedagogical potential. Conversely, a carefully curated digital journal can embody the same depth as its analogue counterpart.

Cultivating Lifelong Practice

Perhaps the most enduring contribution of the sketchbook as a pedagogical tool is the habit it instils. Students who maintain sketchbooks throughout their education often continue the practice into adulthood. It becomes a lifelong companion, a site of reflection and renewal.

In a professional context, artists frequently return to earlier notebooks, mining them for ideas that were not previously realised. What seemed inconclusive at one stage may later reveal unexpected promise. The sketchbook thus resists the linear narrative of progress. It suggests instead a cyclical process, where ideas resurface and evolve.

For educators, encouraging this long view requires patience. Not every page will be successful. Not every concept will lead to a finished work. Yet the cumulative effect of sustained practice is profound.