The Shuttered World: Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II’s Camera

Jaipur’s Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II embraced photography in the 1860s, creating a royal photukhana to explore self‑portraits, palaces and the secluded zenana—melding artistic inquiry with modernising ambition.

In the mid‑nineteenth century, amid the ochre‑clad palaces and rose‑sped lanes of Jaipur, a most unlikely enthusiast took up the camera: Maharaja Sawai Ram Singh II. Long remembered as a progressive ruler who modernised his realm, Ram Singh proved equally modern in his embrace of photography, mastering its technical challenges and bending its expressive possibilities to his own inquisitive will. In a world where the photographer was typically an outsider or a traveller, here was a sovereign turning lens on his own court—and, most intriguingly, on the hidden lives of the women of the zenana.

A Prince’s Passion for the New Art

Born in 1835, Sawai Ram Singh II ascended the throne at the age of nine and quickly distinguished himself as a reformer. He built schools, hospitals, theatres and the Albert Hall Museum; he introduced electricity, modern sanitation and rail links; and he encouraged the study of science and Sanskrit alike. But it was around 1864, upon encountering British photographic practitioners, that his imagination was truly captured.

Ram Singh threw himself into the demanding wet‑collodion process—mixing silver nitrate and collodion, coating glass plates, timing exposures to the split second, and printing positives in his own darkroom. Before long, he had established a fully equipped “photukhana” (picture department) within the City Palace, complete with brass Voigtländer lenses, a trove of chemicals, and his ever‑present journal, in which he recorded each experiment and expedition in meticulous detail. By assuming responsibility for every aspect of production—from sparking the gas lamp in the darkroom at dawn to varnishing his final prints—he signalled his ambition to be not merely a patron of photography but a true practitioner.

Between Thrones and Tripods: The Subjects of a King’s Camera

What did this Maharaja choose to photograph? His subjects encompassed the full sweep of royal life, public spectacle and private reverie.

Self‑Portraits as Self‑Inquiry

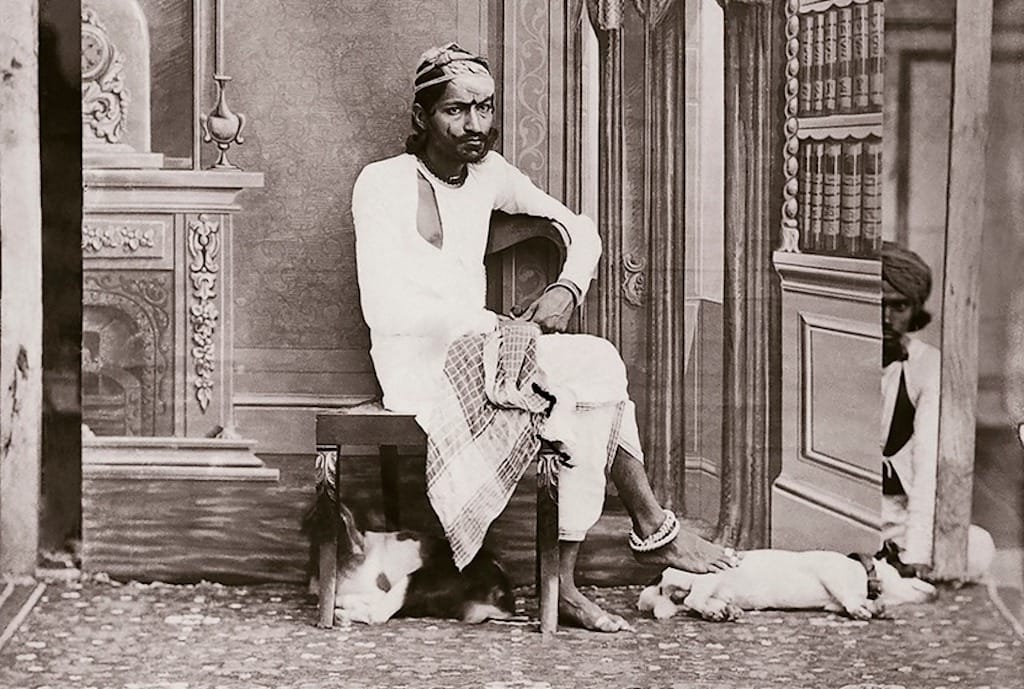

In one series of self‑portraits, Ram Singh adopts different guises: donning martial attire and rifle, evoking the traditional Rajput warrior; draped in saffron robes and rudraksha beads, evoking a Shaivite ascetic; perched at ease with his hound, as companion rather than monarch. These portraits are not mere vanity; they reveal a ruler probing the very notion of identity, using costume and posture to demonstrate that a sovereign could, in his own private sphere, explore alternative selves.

Architectural Studies and Travelography

Long before the era of systematic documentation, the Maharaja journeyed beyond Jaipur with his cumbersome equipment, recording Mughal monuments in Agra, the ghats of Varanasi and the palaces of Lucknow. His images of the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort and the ancient pillar at Mehrauli capture these landmarks in crisp, arresting detail—yet with the subtle shading and compositional sensitivity of an artist rather than the detached eye of a surveyor. These photographs later formed one of the earliest visual archives of India’s architectural heritage.

Zenana Portraiture: Shuttering the Shuttered

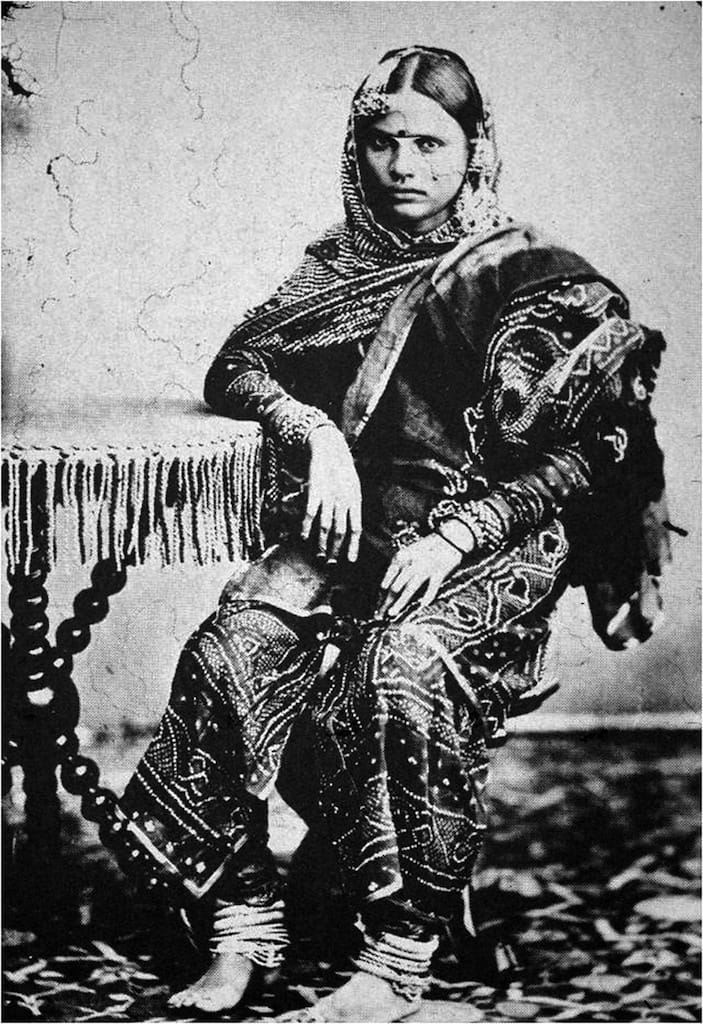

Perhaps the most revolutionary chapter in Ram Singh’s photographic oeuvre was his portrayal of the zenana—the sheltered quarters where royal women lived in seclusion. In an age when Victorian morality and Indian custom converged to keep these women largely hidden from view, his portraits offered an unprecedented glimpse into their lives. Against painted backdrops and furnished with European chairs and drapery, the Maharaja posed his sitters—queens, concubines, dancers and attendants alike—with dignity and grace. His respectful, often collaborative approach contrasts sharply with the objectifying gaze of colonial ethnographers, suggesting instead a nuanced engagement with gender, power and representation.

Technical Mastery and Cultural Ambition

Ram Singh’s photographic pursuits dovetailed neatly with his broader vision for a modern Jaipur. He taught the art to students at his Maharaja’s School of Arts, invited leading practitioners to demonstrate processes in public lectures, and maintained lively correspondence with members of the Bengal Photographic Society. Under his guidance, the photukhana not only produced exquisite images but served as a locus of technical innovation: experiments in stereoscopy, refinements in lens coatings and even early ventures in hand‑colouring prints.

This creative energy was on display at the great Jaipur Exhibition of 1883, which Ram Singh organised as a showcase for local arts and crafts. Photographs occupied a place of honour alongside lacquers, carpets, metalwork and textiles, signalling the medium’s elevation from curiosity to cultural instrument. It was, in the Maharaja’s own words, a means of “uniting tradition and modern method, East and West, in a single vision.”

Eclipse and Rediscovery

After Ram Singh’s death in 1880, the photukhana gradually fell silent. His glass‑plate negatives, brass cameras and meticulously bound albums were packed away in the Madho Niwas, a private precinct of the City Palace, and forgotten by successive generations. It was only in the late twentieth century that scholars and archivists, guided by faint references in the palace registers, reopened those locked rooms. What they found was a treasure trove of some 2,500 glass plates—many bearing the Maharaja’s own annotations—and the optical instruments he so cherished.

Since that rediscovery, exhibitions in Delhi, Melbourne and Europe have introduced Ram Singh’s images to a global audience. Contemporary scholars now recognise that his work offers more than a dossier of royal spectacle; it provides an intimate chronicle of a society in transition, viewed through the lens of one of its most forward‑thinking figures.