The Scream: What Was Munch Really Screaming About?

Edvard Munch’s 'The Scream' captures more than personal agony—it channels the existential dread of modern life. But was Munch really screaming? Or was he simply listening to the world cry out?

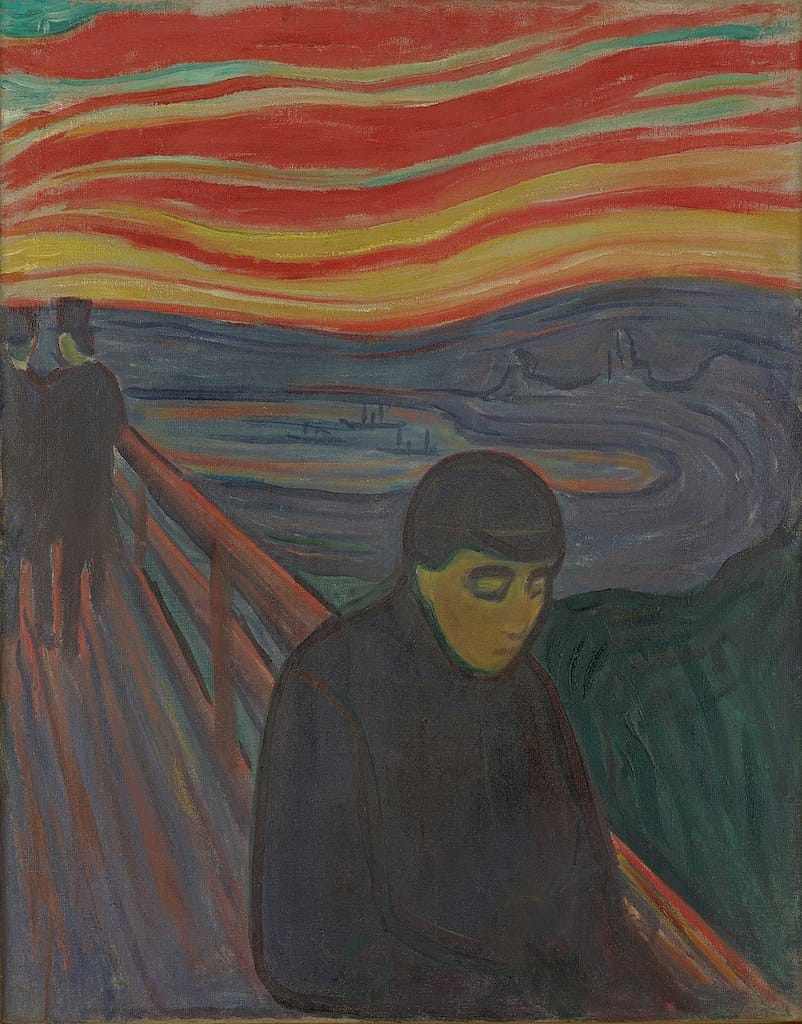

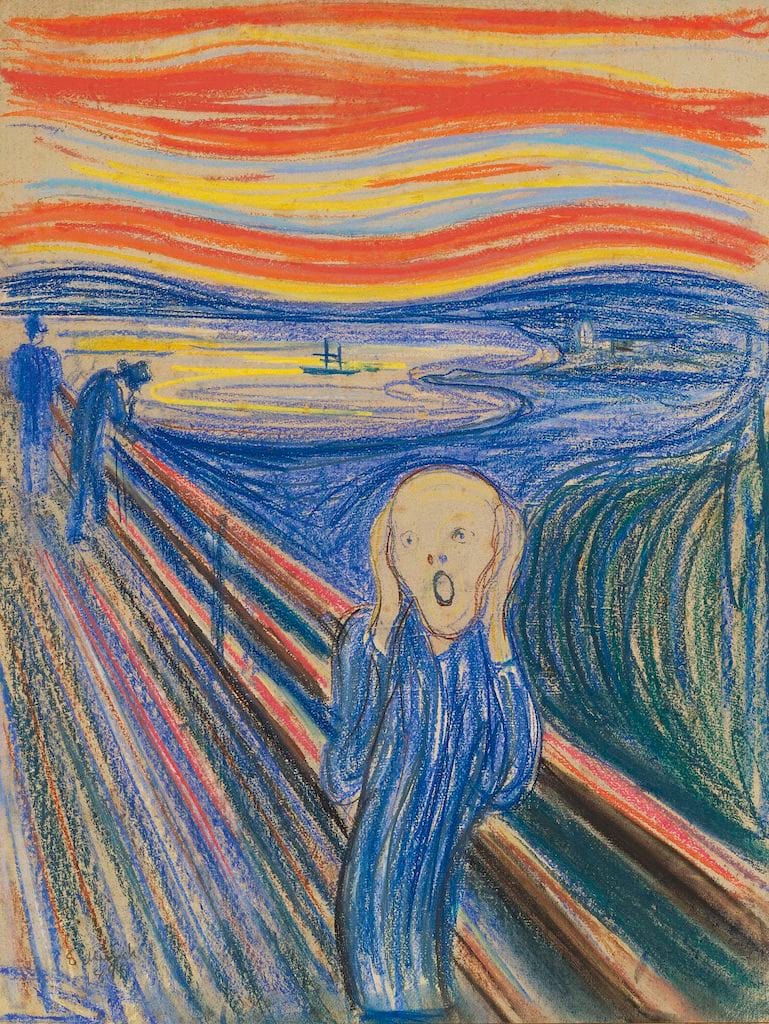

Few images in modern art are as universally recognisable—or as viscerally unsettling—as Edvard Munch’s The Scream. With its swirls of colour, contorted figure, and eerie backdrop, the painting has become a shorthand for existential dread, anxiety, and inner turmoil. But what was Munch really screaming about? Was it a personal anguish? A reaction to modern life? Or perhaps something else entirely?

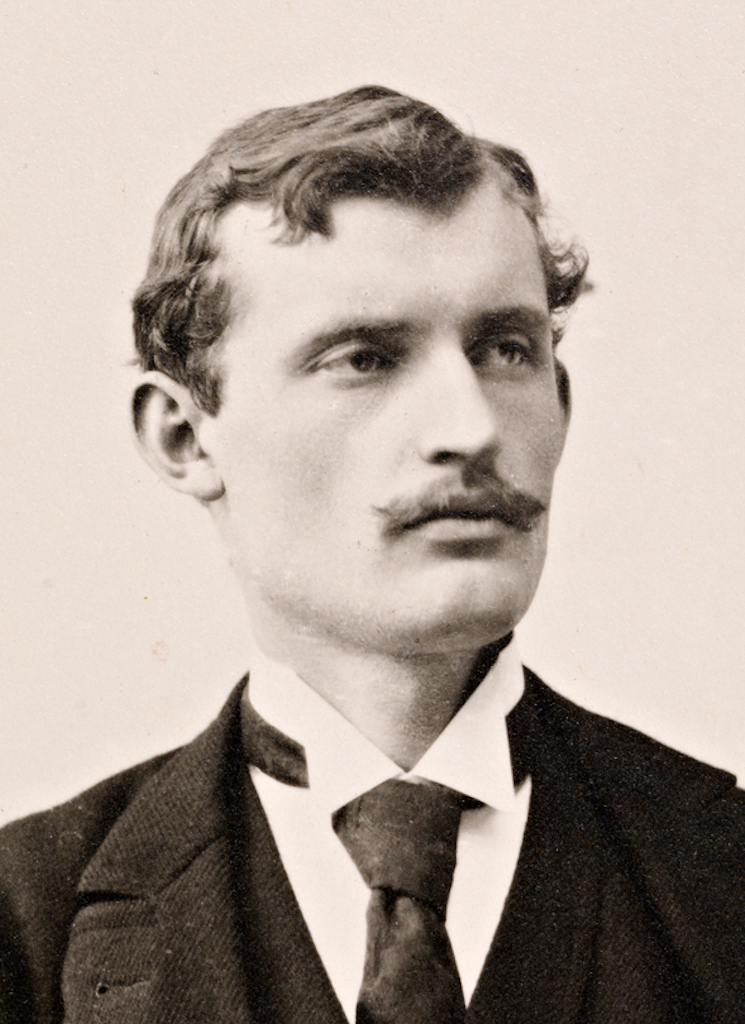

To understand The Scream, we must first consider the man behind the painting—his life, his psyche, and his times. Born in 1863 in Løten, Norway, Edvard Munch grew up amidst illness, death, and emotional instability. His mother died of tuberculosis when he was just five, and his beloved sister Sophie succumbed to the same disease nine years later. His father, a deeply religious man, was said to have veered into fanatical expressions of faith following these tragedies, instilling in Munch a profound sense of guilt and fear of damnation. It’s fair to say that death and anxiety were constants in Munch’s early life—and they would remain central themes throughout his career.

The painting we know today as The Scream—actually part of a series that includes two painted versions and several prints—was completed in 1893. But the moment it depicts is rooted in a personal experience Munch described in his diary a few years earlier:

“I was walking along the road with two friends – the sun was setting – suddenly the sky turned blood red – I paused, feeling exhausted, and leaned on the fence – there was blood and tongues of fire above the blue-black fjord and the city – my friends walked on, and I stood there trembling with anxiety – and I sensed an infinite scream passing through nature.”

It’s this passage that holds the key to the painting’s essence. Munch wasn’t depicting a person screaming. Rather, the figure is reacting to a scream emanating from the world itself. The distinction is critical—and revealing. It suggests that The Scream is not merely a portrait of personal terror, but a broader evocation of existential despair: the anxiety of being alive in a world that feels ungraspable, chaotic, even malevolent.

Art historians have long debated the symbolism within the painting. The central figure—genderless, skull-faced, mouth agape—is rendered in a way that defies traditional portraiture. Some have speculated that it’s a self-portrait, but it seems more like a stand-in for the everyman, or indeed for humanity at large. The swirling sky, painted in lurid shades of red, orange and ochre, has been linked to atmospheric effects caused by the 1883 eruption of Krakatoa, which reportedly gave rise to unusually vivid sunsets across Europe for months afterwards. Could Munch have witnessed one such sky and transmuted it into an emotional vision? Or was it entirely symbolic—a visual metaphor for inner psychological disturbance?

Others have read the painting through the lens of burgeoning modernity. The late 19th century was a time of rapid technological change, urbanisation, and social upheaval. The city depicted in the background is Oslo (then Christiania), where Munch lived and worked. Though distant in the painting, its presence is keenly felt. The modern city, with its noise, pace and impersonality, may well have fuelled Munch’s disorientation. The two shadowy figures walking ahead on the bridge—unaware of his crisis—might symbolise society’s indifference to individual suffering. Isolation, then, is another theme: that sense of being utterly alone amidst a world in motion.

Psychological interpretations abound. Munch’s work predates Freud’s major writings by only a few years, and his themes of anxiety, neurosis, and repression are startlingly prescient. Indeed, Munch’s entire Frieze of Life series, to which The Scream belongs, charts the emotional trajectory of the human experience—love, jealousy, despair, and death. If the Mona Lisa is a quiet enigma, The Scream is an unfiltered scream of the soul.

But let us not mistake Munch’s emotional honesty for lack of artistic sophistication. The composition of The Scream is calculated and deliberate. The bridge’s strong diagonals draw the viewer’s eye toward the central figure, whose curves echo the shape of the swirling sky, uniting foreground and background in a single, anxious rhythm. The colours are not naturalistic but expressive, reinforcing mood over realism. The technique itself—using tempera and crayon on cardboard—adds to its raw, urgent quality.

And yet, despite its deep personal roots, The Scream has transcended biography to become a universal icon. It has inspired countless parodies and homages, appeared in films, cartoons, and even emojis. In an age of climate anxiety, political instability, and digital overload, the painting resonates more than ever. Munch himself could never have predicted that his expression of personal anguish would become the visual vocabulary of a century—and beyond.

So what, ultimately, was Munch “screaming” about? The beauty of The Scream is that it allows for multiple readings. It is a painting of anxiety, yes—but also of recognition. It reflects not just Munch’s inner life, but our own. The scream is in the air, in nature, in the city, in ourselves. It is a silent howl that anyone who has felt overwhelmed, alienated or afraid will recognise.

Perhaps that’s why the painting endures. It does not offer answers or comfort. Instead, it validates the experience of dread—it acknowledges that sometimes, the world does feel too much, and that it’s okay to pause on the bridge, to tremble, and to listen to that infinite scream echoing through the universe.

In the end, The Scream is less a question of what Munch was screaming about, and more an invitation to ask ourselves: what are we screaming about?