The 'Left-Brained Artist': The Science Behind Creativity

Creativity is not confined to one hemisphere of the brain. This article explores how artists draw on interconnected neural networks, combining analytical reasoning with imaginative insight to produce meaningful and innovative work.

For decades, popular culture has promoted the idea that people fall into two neat categories. Some are left brained, analytical and methodical, while others are right brained, imaginative and free thinking. This binary framing has appealed to artists and audiences alike, offering a seemingly simple explanation for why certain individuals gravitate towards creative pursuits. Yet neuroscience has shown that the truth is far more interesting and far more complex. Creativity is not confined to one hemisphere, nor is artistic practice the exclusive domain of the right side of the brain. Instead, creative achievement draws on highly interconnected networks across the entire brain. The so called left brained artist is not a contradiction but a vivid reminder that art is as much a cognitive process as it is an emotional one.

The Myth of the Split Brain

The origins of the left brain and right brain myth can be traced to research conducted in the 1960s on patients whose hemispheres had been surgically separated as a treatment for epilepsy. Scientists noticed that the two sides of the brain seemed to specialise in different functions. The left hemisphere tended to handle language and analytical reasoning while the right hemisphere was more involved in spatial abilities and face recognition. These findings were revolutionary at the time, yet they were also quickly simplified and exaggerated in the public imagination.

Over time, the idea took root that creative people rely mainly on their right hemisphere while logical individuals depend primarily on the left. This narrative spread into self help books, school workshops, online personality tests and even art therapy practices. However, modern neuroscience has shown that this division is inaccurate. Although hemispheric specialisation exists, both hemispheres are involved in almost every complex task, including those we associate with creativity. Artistic thinking requires a blend of rational problem solving, emotional processing, sensory perception and conceptual flexibility. These functions operate across the brain rather than in isolated compartments.

Creativity as a Whole Brain Process

One of the most enduring insights from recent brain imaging research is that creativity is a whole brain activity. When artists sketch, compose, choreograph or sculpt, regions in both hemispheres activate simultaneously. For example, the visual cortex processes incoming stimuli, the frontal lobes coordinate planning and decision making, the limbic system contributes emotional colouring and the parietal lobes help with spatial reasoning. Creativity relies on a dynamic conversation between these areas.

Two key networks have emerged as especially important for creative work. The first is the default mode network, which activates during moments of introspection, mind wandering and spontaneous idea formation. The second is the executive control network, which supports focus, planning and the evaluation of ideas. Artists constantly shift between these modes. They drift into imaginative exploration, then engage the evaluative systems necessary to refine and execute their vision. The back and forth between these networks gives creativity its characteristic rhythm of expansion and consolidation.

This understanding challenges the stereotype of the disorganised, impulsive artist who relies solely on inspiration. In practice, many creative practitioners depend on structure and discipline, qualities often associated with left brain thinking. They combine imaginative leaps with methodical repetition, experimentation with rigorous craft, and spontaneity with patience. The artist who is perceived as left brained is often deploying an extraordinary level of cognitive control as they navigate the complexities of their medium.

The Role of Logic in Artistic Practice

Far from being opposed to creativity, logical reasoning plays a crucial role in many artistic disciplines. A photographer calculating exposure, an architect balancing weight distribution, a musician composing within harmonic structures, or a graphic designer considering typographic hierarchy all rely on analytical thinking. These skills draw heavily on regions associated with sequential reasoning and verbal processing, traditionally attributed to the left hemisphere.

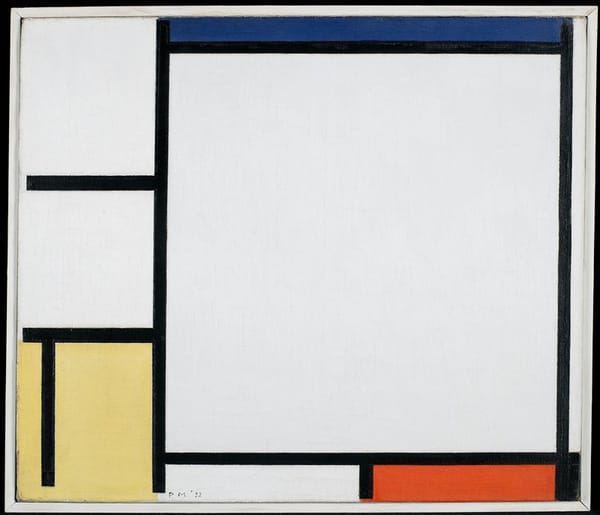

Take the example of a painter designing a composition. They must consider proportions, symmetry, contrast and colour theory. These decisions require a deliberate cognitive process. Similarly, a choreographer must map movement sequences in space, count rhythms, and anticipate transitions. Each step involves both intuition and analysis. Even in abstract or experimental art, choices about material, technique and form involve structured decision making.

Artists often speak of intuition, yet intuition itself is the product of internalised knowledge and repeated practice. Neuroscientists describe this as procedural memory, which develops through countless hours of rehearsal and experimentation. What may appear as a spontaneous creative act is often grounded in a deep well of learned patterns. These patterns are processed in brain regions such as the basal ganglia and cerebellum, which help automate complex sequences, allowing the artist to focus on expression rather than mechanics.

Divergent and Convergent Thinking

Psychologists often distinguish between two types of thinking that underpin creativity. Divergent thinking involves generating multiple ideas, associations or possibilities. Convergent thinking involves narrowing those options to identify the most effective solution. Artists use both forms of cognition throughout the creative process.

Divergent thinking is associated with openness, playfulness and the ability to make unexpected connections. This mode aligns with the stereotype of the right brained artist. However, convergent thinking is equally essential and relies on structured reasoning and evaluation. Without convergent thinking, creative projects would remain incomplete or incoherent.

The most successful artists manage to balance these modes. They allow themselves moments of free exploration yet return to a framework that helps shape their ideas into finished work. This interplay mirrors the collaboration between the brain's networks rather than the dominance of one hemisphere. It also explains why many creative individuals thrive when they establish routines, deadlines or constraints. Constraints can stimulate creativity by forcing the brain to engage its analytical functions while still encouraging inventive solutions.

Why the Left Brained Artist Matters

The figure of the left brained artist challenges outdated assumptions about what creativity looks like. It demonstrates that artistic excellence is not solely the result of innate talent or mystical inspiration. Instead, it emerges from a sophisticated interplay between imagination and discipline, intuition and analysis, freedom and structure. By valuing the contributions of the so called left brain, we acknowledge the cognitive sophistication that underpins creative work.

This perspective also reinforces the idea that creativity is accessible to everyone. The notion that only naturally right brained individuals can be artists has discouraged many people from pursuing creative activities. Understanding that creativity involves skills that can be learned and strengthened allows more individuals to participate in artistic practices. It also encourages educators to design programmes that develop both imaginative and analytical capacities, rather than reinforcing narrow stereotypes.

A More Nuanced Understanding of Creativity

Artistic innovation has always relied on a balance of contrasting impulses. Renaissance artists combined scientific observation with aesthetic beauty. Contemporary digital artists blend coding with conceptual thinking. Architects merge engineering principles with expressive design. Photographers use technological precision to capture fleeting emotional moments. Across disciplines, the most compelling creative work emerges from this integration.

Recent advances in neuroscience support this view by illustrating how fluid and interconnected the brain truly is. Creativity does not reside in one hemisphere. Instead, it emerges from patterns of connectivity, cognitive flexibility and the ability to switch between mental states. Artistic thinking is both rational and emotional, structured and exploratory, grounded in memory yet open to new possibilities.

Ultimately, the idea of the left brained artist reflects a broader truth about creativity. It is not a singular trait but a constellation of processes that draw on every part of the brain. Artistic work thrives when individuals cultivate both systematic thinking and imaginative freedom. The science of creativity reveals that far from being opposites, these qualities enhance and reinforce one another.

Conclusion

The myth of the split brain has long shaped how people perceive creativity. While it offered a simple narrative, modern science paints a far richer picture. Artistic expression relies on multiple networks that span the entire brain, blending analytical reasoning with emotional insight and intuitive exploration with disciplined practice. The left brained artist is therefore not an anomaly but a powerful example of how creativity actually functions.