The Forgotten Souvenir: Reviving Mica Paintings at MAP

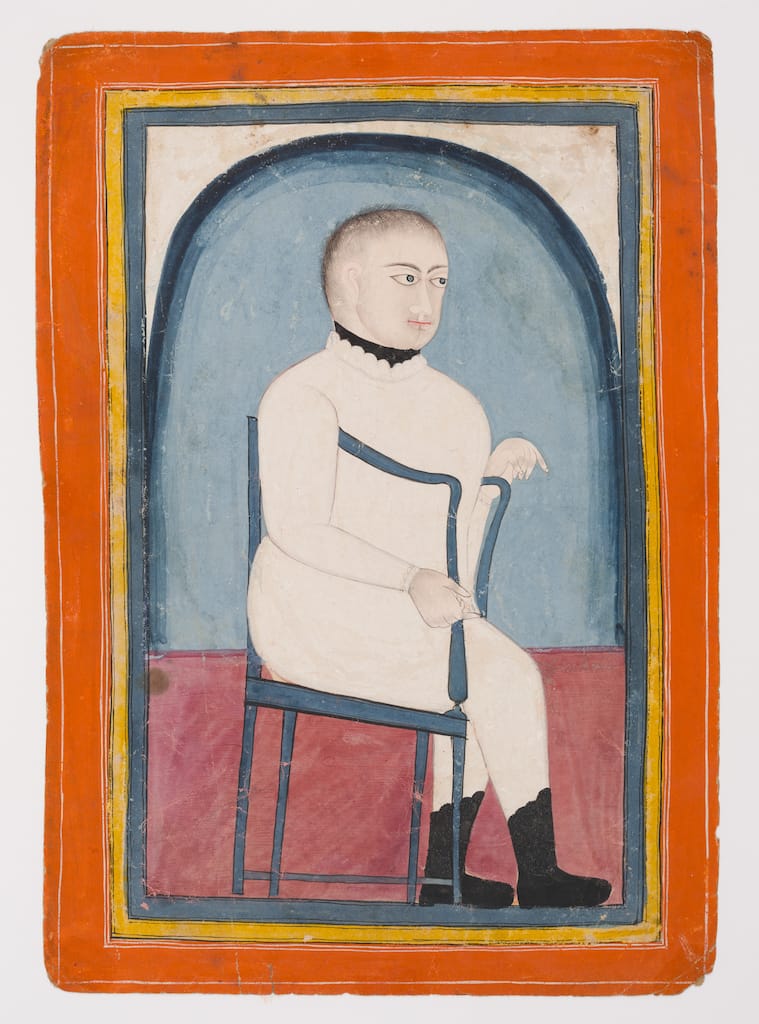

Discover the revival of 19th-century mica paintings at MAP, a forgotten Indian art form blending translucence and tradition. Explore how these delicate souvenirs are being preserved and celebrated, bridging history and contemporary appreciation.

Running until February 23, 2025, the Museum of Art & Photography (MAP), Bengaluru, will host The Forgotten Souvenir, an unprecedented exhibition curated by Khushi Bansal. This exhibition sheds light on mica paintings—a delicate and often-overlooked art form—exploring their artistic, historical, and socio-political significance.

“Mica painting is a relatively forgotten practice, with little to no exhibitions dedicated to it,” Bansal shares. “We felt it was crucial to bring this unique painting tradition to the forefront and make it more widely known as many people are unaware of the use of mica in painting.”

Mica as a Medium

Mica became popular among Indian artists during the colonial era for its affordability, portability, and ability to mimic the sheen of European glass paintings. “It was significantly cheaper than other materials and mimicked the look of European glass paintings, which were highly valued at the time,” Bansal explains.

The material’s unique properties influenced the aesthetic qualities of mica paintings. “The non-porous surface of mica meant that it did not absorb pigment, resulting in paintings that were exceptionally bright and vivid,” Bansal notes. Despite their brilliance, these paintings were often less intricate, created quickly to meet the demands of commercial production.

Evolving Patronage

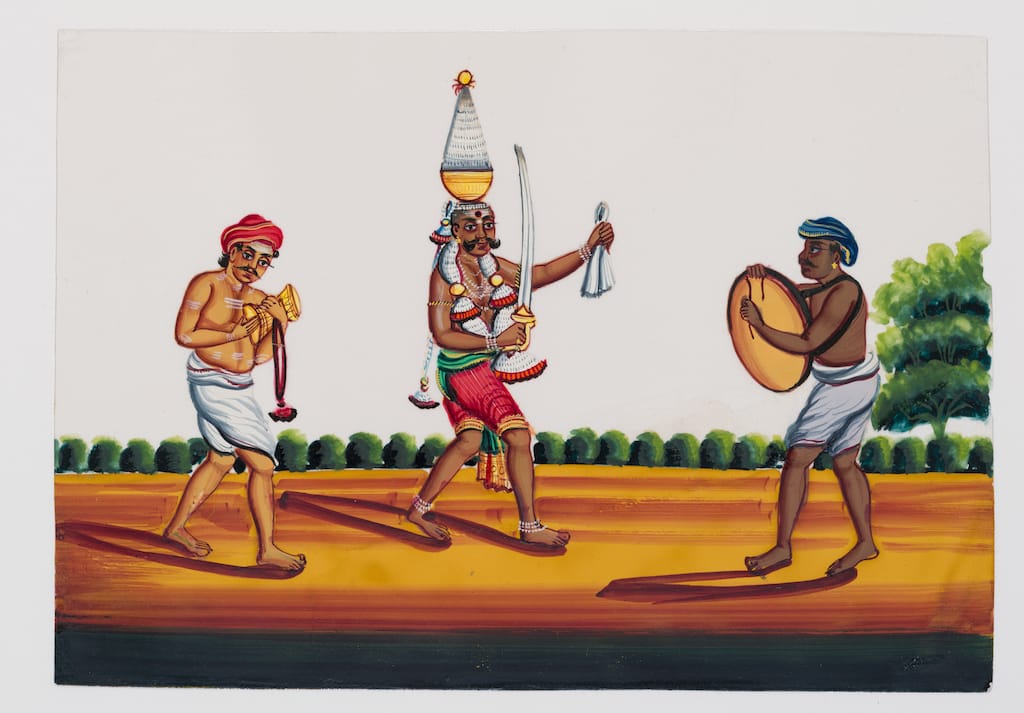

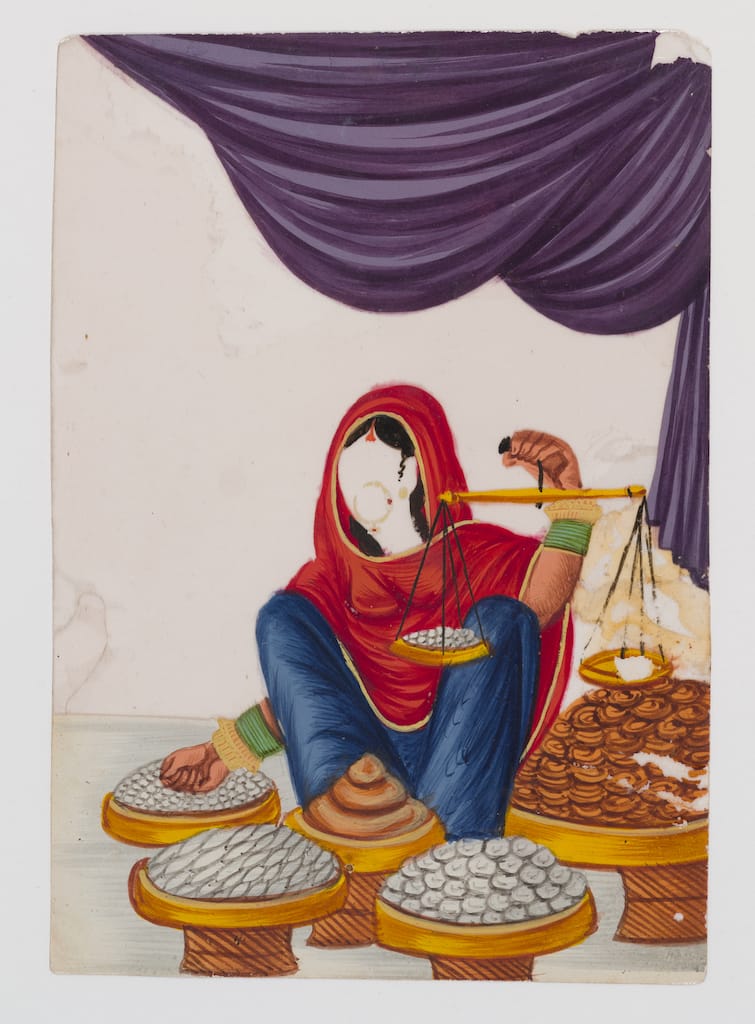

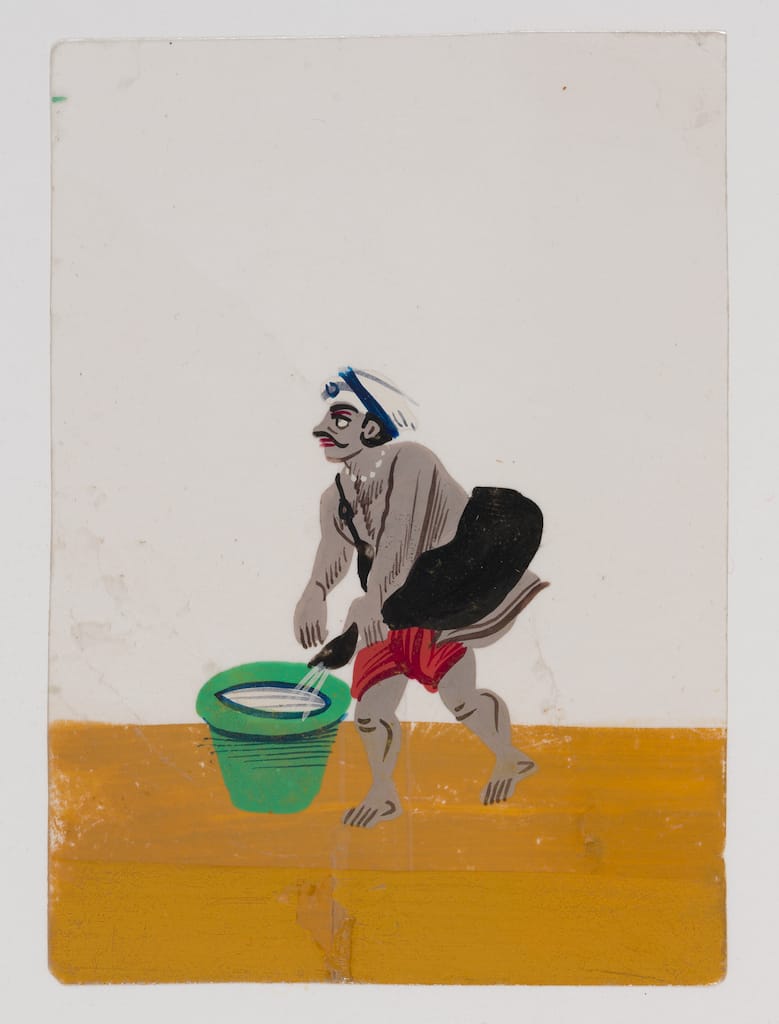

The rise of mica paintings coincided with significant cultural shifts in India. With the decline of royal patronage, artists turned to new markets, producing works for British officials, traders, and travellers. “The imagery drastically shifted, depicting trades, occupations, and caste,” Bansal observes. “The patrons now sought to consume and document India.”

This interplay of European and Indian influences is evident in the artworks, which reflect not only colonial tastes but also regional adaptations. As Bansal elaborates, “Different areas adopted their own styles and techniques, making it easier to trace the origins of individual paintings.”

Regional Variations

Mica paintings from centres like Murshidabad, Patna, and Trichinopoly showcase distinct regional characteristics. “The Murshidabad and early Patna mica paintings are very similar and feature fuller backgrounds and faces,” Bansal explains. “The faceless micas, where the backgrounds were sold separately, are most definitely from Patna.”

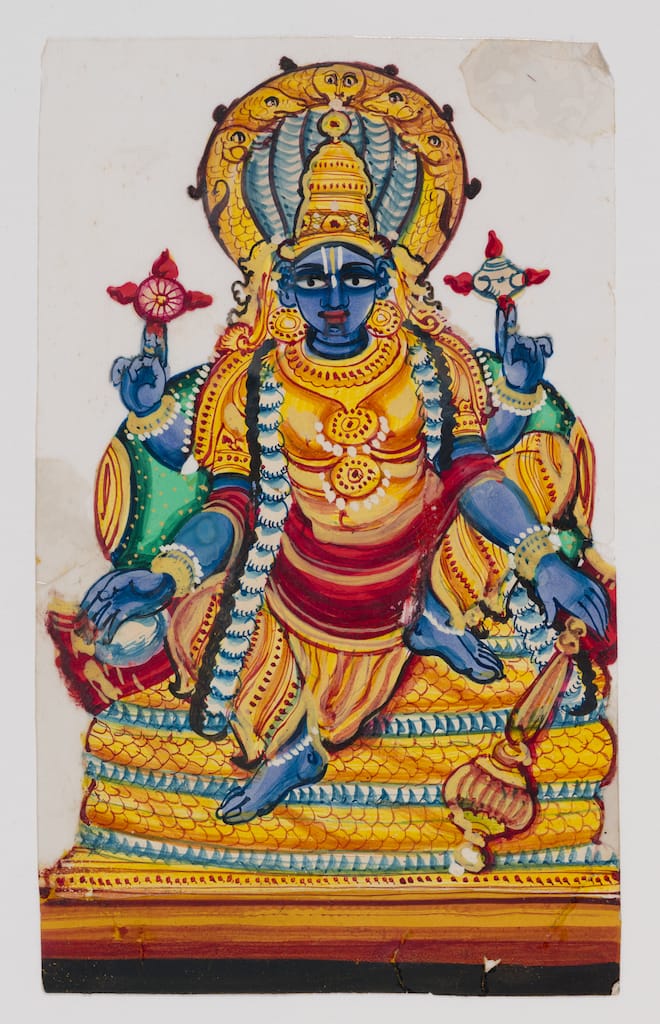

In contrast, Trichy examples stand out for their vibrant use of colour and thematic focus. “The early Trichy ones often feature gods and goddesses, indicative of a time when royal patronage still existed in the region,” says Bansal. “Later Trichy examples depicted daily life, occupations, festivals, and processions.”

Colonial India Through the Lens of Mica Paintings

These paintings offer a window into colonial India’s societal structures, capturing trades, professions, and the dynamics of class and caste. “The British reduced the identity of the entire Indian population down to what their occupation was,” Bansal remarks. “Mica paintings serve as a medium for studying Indian society, capturing and freezing the identities of individuals and communities.”

Beyond their artistic value, these works reveal the socio-political climate of their time, illustrating the broader consolidation of imperial dominance through visual culture.

The Challenges of Curating and Conserving Mica Paintings

Presenting these fragile works posed significant challenges for the curatorial team. “Mica is incredibly delicate, and we had to approach the display keeping that in mind,” Bansal explains. The conservation team worked meticulously to ensure the artworks met museum standards while retaining their natural wear and tear. “Only then do you understand the passage of time and the period we are looking at,” she adds.

The selection of works was also guided by their stability. “We tried to retain the natural wear and tear,” says Bansal. “Our selection is based on the works which were stable enough to be shown for three months because these paintings probably could not withstand a longer display period.”

A Multifaceted Experience

Beyond the artworks, The Forgotten Souvenir offers visitors an immersive and interactive experience. The accompanying short film, Moments before Mutiny by Amit Dutta, provides a poignant perspective on the colonial history tied to mica paintings. “The film’s eerie and unsettling tone encourages visitors to confront the uncomfortable histories tied to the tradition of painting on mica,” Bansal explains.

Additionally, the interactive game Made in Mica invites visitors to engage closely with the artworks. “The game prompts close looking and active engagement,” Bansal notes.

A tactile display and a booklet featuring a commissioned essay by artist Rahee Punyashloka further enrich the exhibition, offering deeper insights into the subject matter.

Mazumdar-Shaw Philanthropy

The exhibition was made possible by the generous support of the Mazumdar-Shaw Philanthropy. “Their support gave us the flexibility to create an immersive and multifaceted experience,” Bansal shares. “We were able to experiment with innovative display techniques while ensuring the utmost care for these incredibly fragile objects.”

This backing enabled the inclusion of unique elements such as sound through the film, touch through tactile displays, and interaction through the game, creating a holistic experience for visitors.

A Forgotten Tradition

The Forgotten Souvenir is not just an exhibition; it is a powerful testament to the resilience and adaptability of India’s artistic heritage. Through meticulous curation and innovative presentation, the exhibition not only revives a neglected art form but also prompts reflection on the complex intersections of art, culture, and colonial history. By spotlighting mica paintings, MAP ensures that this fragile yet vibrant tradition is not only remembered but celebrated and preserved.