The Evolution of Greek Sculpture: From Archaic to Hellenistic Periods

Greek sculpture evolved from the rigid forms of the Archaic period to the naturalism of the Classical era, culminating in the emotional and dynamic works of the Hellenistic period, reflecting changing societal values and artistic innovation.

Greek sculpture is a testament to the artistic and cultural advancements of ancient Greece, reflecting the society's evolving values, techniques, and influences. The journey of Greek sculpture from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods spans several centuries, each marked by distinct styles and innovations that have left an indelible impact on the history of art. This essay delves into the evolution of Greek sculpture across these three significant periods: Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic.

The Archaic Period (c. 700–480 BCE)

The Archaic period is characterized by its initial steps towards realistic representation, moving away from the more abstract and rigid forms of earlier times. The most iconic sculptures from this period are the kouroi (singular: kouros) and korai (singular: kore), which are free-standing statues of young men and women, respectively.

Characteristics of Archaic Sculpture

- Rigid Posture and Symmetry: The kouroi and korai exhibit a frontal, symmetrical posture, with a stiff, upright stance. This reflects the influence of Egyptian sculpture, which the Greeks were exposed to through trade and interaction.

- Stylized Features: The faces of Archaic sculptures often display the "Archaic smile," a fixed, somewhat enigmatic smile intended to animate the otherwise stiff facial features. Hair is stylized into patterned rows or beaded braids.

- Idealized Form: While there is an emphasis on idealized human forms, the anatomy is not entirely realistic. Muscles and body parts are often exaggerated or simplified.

Notable Examples

- Kouros of Anavyssos (c. 530 BCE): This statue exemplifies the typical kouros, with its rigid stance, stylized hair, and the characteristic Archaic smile. It shows a gradual shift towards more naturalistic proportions and anatomy.

- Peplos Kore (c. 530 BCE): A statue of a young woman wearing a peplos (a type of garment), the Peplos Kore demonstrates the period's approach to depicting female figures, focusing on drapery and modesty.

The Classical Period (c. 480–323 BCE)

The Classical period marks a significant transformation in Greek sculpture, characterized by increased naturalism, dynamic movement, and a focus on idealized but realistic human forms. This era saw the peak of Greek artistic achievement, influenced by political stability and intellectual advancements.

Characteristics of Classical Sculpture

- Contrapposto: Sculptors introduced the contrapposto stance, where the weight is shifted onto one leg, creating a sense of movement and relaxed naturalism. This technique marked a departure from the rigid postures of the Archaic period.

- Realistic Anatomy: There was a heightened understanding of human anatomy, leading to more accurate and lifelike depictions of muscles, bone structure, and movement.

- Idealized Beauty: While realism improved, the Classical period maintained an idealized aesthetic. Figures were depicted in their perfect form, embodying the Greek ideals of beauty and harmony.

Notable Examples

- Kritios Boy (c. 480 BCE): One of the earliest examples of contrapposto, the Kritios Boy represents a significant shift towards naturalism, with a more relaxed pose and realistic depiction of muscle and bone structure.

- Discobolus (Discus Thrower) by Myron (c. 450 BCE): This sculpture captures the dynamic motion of an athlete in action, showcasing the Classical period's emphasis on movement and anatomical accuracy.

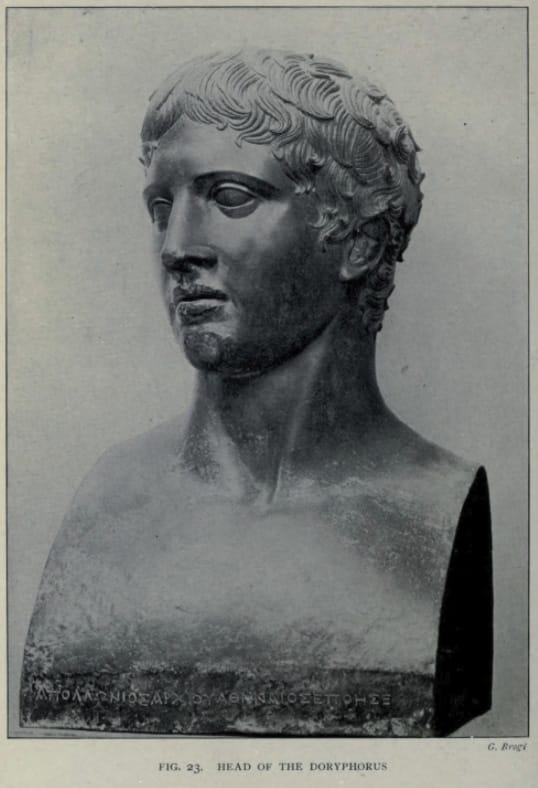

- Doryphoros (Spear Bearer) by Polykleitos (c. 440 BCE): Known for its portrayal of the perfect male form, this statue exemplifies the Classical ideals of proportion, balance, and harmony. Polykleitos' work was a practical demonstration of his treatise, the "Canon," which outlined the principles of ideal human proportions.

The Hellenistic Period (c. 323–31 BCE)

The Hellenistic period followed the conquests of Alexander the Great, leading to the spread of Greek culture across a vast territory. This era is marked by diversity in artistic expression, emotional intensity, and a blend of realism with dramatic effect.

Characteristics of Hellenistic Sculpture

- Emotional Expression: Hellenistic sculptures often depict intense emotions, capturing moments of pain, joy, anguish, and ecstasy. This shift reflects a broader range of human experience and psychological depth.

- Complex Poses and Composition: Sculptors experimented with more complex and dynamic poses, creating intricate compositions that conveyed movement and narrative.

- Realism and Individuality: There was an increased focus on realistic details and individual characteristics, moving away from the idealized forms of the Classical period. This included depictions of old age, children, and ethnic diversity.

Notable Examples

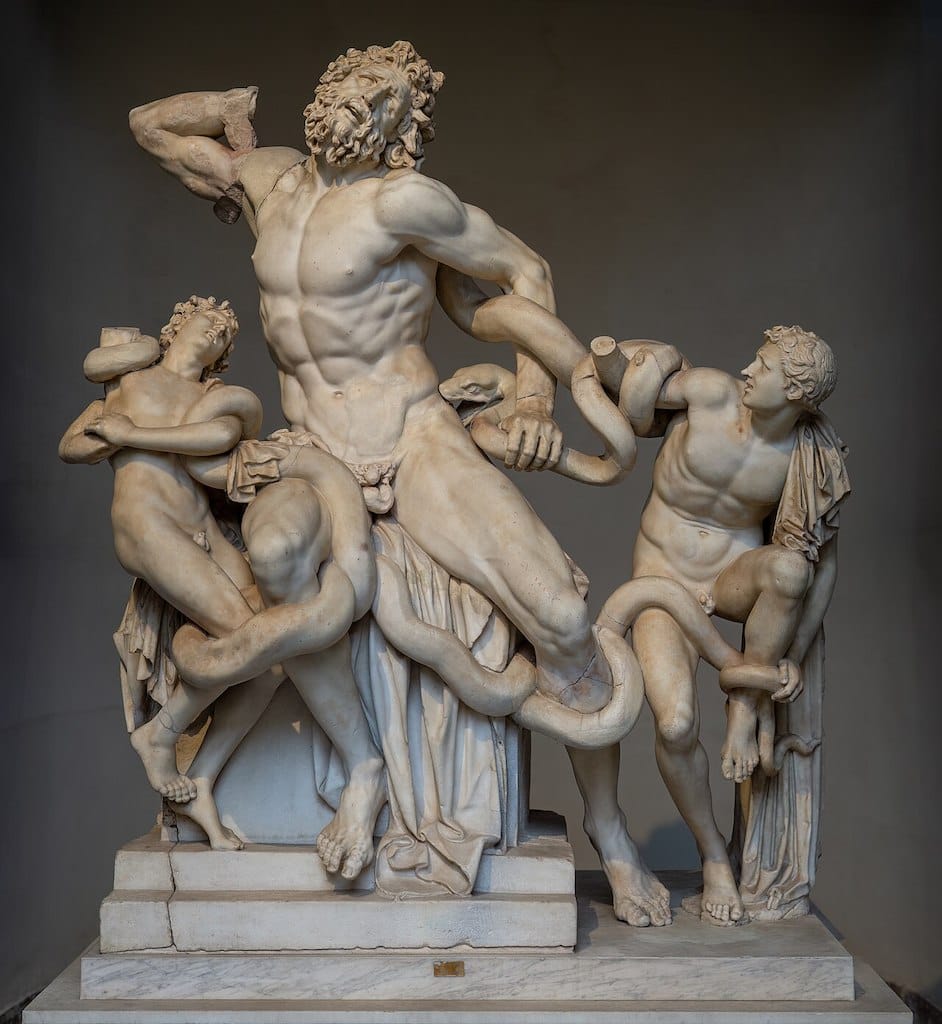

- Laocoön and His Sons (1st century BCE): This dramatic sculpture group depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons being attacked by sea serpents. The intense emotion and intricate composition exemplify the Hellenistic focus on drama and movement.

- Winged Victory of Samothrace (Nike of Samothrace) (c. 190 BCE): Celebrating the Greek goddess Nike, this statue is renowned for its sense of movement and the realistic depiction of drapery caught in the wind, creating a powerful image of divine triumph.

- Aphrodite of Melos (Venus de Milo) (c. 150–125 BCE): This statue blends Classical idealism with Hellenistic sensuality, depicting the goddess Aphrodite in a naturalistic yet idealized manner.

Conclusion

The evolution of Greek sculpture from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods illustrates a journey of artistic innovation and cultural expression. Beginning with the rigid and stylized forms of the Archaic period, Greek sculptors gradually embraced naturalism and movement during the Classical period, culminating in the emotional and dynamic works of the Hellenistic era. Each period reflects the changing values and influences of Greek society, leaving a legacy that has profoundly impacted the development of Western art.