The Art of Christmas: Depicting the Nativity Through the Ages

From radiant Renaissance masterpieces to evocative Baroque drama, the Nativity has inspired centuries of artistic brilliance. Discover how artists have reimagined this timeless Christmas story, blending spirituality, culture, and innovation across history.

The story of Christ’s birth has long captivated humanity, inspiring countless artists across centuries to depict its profound symbolism and spiritual resonance. Whether through the intricate strokes of Renaissance masters or the bold abstractions of modern interpretations, the Nativity scene offers a lens through which to trace the evolution of artistic styles, cultural values, and theological thought. This article explores how depictions of the Nativity have transformed over the ages, celebrating their enduring relevance during the Christmas season.

Early Christian Art

The earliest depictions of the Nativity appeared in catacombs and basilicas of early Christians in the 3rd and 4th centuries. These were less elaborate, focused on iconography rather than narrative depth. The Virgin Mary was often depicted seated, holding the infant Christ, while Joseph and the Magi were symbolically present.

In mosaics, such as those at Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome (5th century), Christ’s birth is woven into larger biblical narratives. The simplicity of these works reflected the humility and spiritual purity central to early Christian theology. The star of Bethlehem and the stable were symbolic rather than naturalistic, underscoring a universal, timeless message.

The Medieval Period

By the Middle Ages, the Nativity evolved into a more narrative subject, fuelled by the rise of illuminated manuscripts and the Gothic aesthetic. The Book of Hours, a devotional manuscript popular among the European elite, frequently featured intricately painted Nativity scenes. These illuminated pages, resplendent with gold leaf, often framed Mary and the Christ child in elaborate settings, surrounded by angels and shepherds.

The Nativity also became central in church sculptures and stained glass. Gothic cathedrals like Chartres and Notre Dame showcased the birth of Christ in radiant glass panels, combining vibrant colours with intricate storytelling. These depictions emphasised the divinity of Christ while reflecting the ornate, hierarchical nature of medieval European society.

The Renaissance

The Renaissance ushered in an era of artistic sophistication and humanism, where the Nativity reached unparalleled heights in its representation. Artists such as Sandro Botticelli, Leonardo da Vinci, and Fra Angelico redefined religious art, blending classical ideals with Christian themes.

One iconic example is Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity (1500), which combines traditional Nativity imagery with apocalyptic undertones, reflecting the political and spiritual uncertainty of the time. Similarly, Fra Angelico’s frescoes at the Convent of San Marco in Florence exude a serene spirituality, balancing human tenderness with divine grace.

Renaissance artists also infused their Nativity scenes with naturalistic detail. The stable was often painted with meticulous realism, while figures were portrayed with emotion and individuality. This period saw a growing emphasis on the humanity of Christ, reflected in the tender interactions between Mary, Joseph, and the infant Jesus.

Baroque Drama

The Baroque period marked a dramatic shift in Nativity art, with artists employing chiaroscuro and dynamic composition to evoke emotional intensity. Caravaggio’s Adoration of the Shepherds (1609) exemplifies this, with stark contrasts of light and shadow drawing the viewer’s attention to the Christ child at the centre.

Peter Paul Rubens, known for his exuberant style, infused his Nativity scenes with movement and grandeur. In works like Adoration of the Magi (1624), Rubens utilised rich colours, swirling compositions, and expressive figures to convey the magnitude of Christ’s arrival.

These dramatic depictions mirrored the Counter-Reformation’s emphasis on evoking spiritual devotion through sensory engagement, with art serving as a powerful tool for religious expression and persuasion.

Regional Variations

The Nativity’s portrayal also varied across regions, influenced by local cultures and traditions. In Northern Europe, artists like Jan van Eyck and Hugo van der Goes introduced detailed realism and symbolic elements into their works, such as the lamb symbolising Christ’s sacrifice.

In contrast, Spanish and Latin American Nativity scenes often included indigenous elements. These artworks, shaped by colonial encounters, blended Christian iconography with local artistic traditions, resulting in vibrant, hybrid interpretations.

Similarly, Byzantine icons maintained a unique stylisation, with golden backgrounds and solemn figures emphasising the eternal and unchanging nature of Christ’s birth.

Modern and Contemporary Interpretations

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the Nativity continued to inspire, albeit through new artistic lenses. Impressionist and Post-Impressionist artists reimagined the traditional scene with innovative techniques. Paul Gauguin’s Nativity (Be Be) (1896) set the birth of Christ in a Tahitian landscape, reflecting his fascination with indigenous cultures and spirituality.

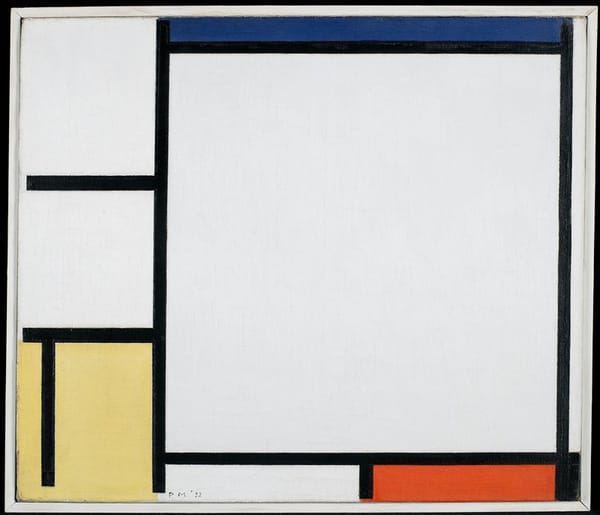

Contemporary artists have pushed boundaries further, employing abstraction and conceptualism to reinterpret the Nativity. British artist Tracey Emin’s The Nativity (2002) uses neon light to depict the scene, blending modern materials with traditional themes.

Modern Nativity art often addresses broader societal issues, from migration and poverty to environmental concerns, framing the story of Christ’s birth as a universal message of hope and resilience.

Themes and Symbolism in Nativity Art

Throughout history, Nativity art has been rich in symbolism. The star of Bethlehem, a guiding light for the Magi, symbolises divine guidance and hope. The stable and manger underscore Christ’s humility, while animals like oxen and donkeys often signify patience and steadfastness.

The interplay of light and shadow—particularly prominent in Baroque works—echoes theological themes of salvation and redemption, with Christ as the light of the world dispelling darkness.

These recurring motifs ensure that the Nativity remains timeless, resonating across cultures and eras.

Conclusion

What makes the Nativity such a compelling subject for artists, even today? Its universal themes—love, humility, and hope—transcend religious boundaries. The scene’s simplicity allows for endless reinterpretation, accommodating both traditional devotion and contemporary innovation. For modern audiences, Nativity art serves as a bridge between past and present, reminding us of the enduring power of storytelling in celebrating the spirit of Christmas.