South Asian Sculptures: From Mohenjo-Daro to the Gupta Empire

From the intricate sculptures of the Indus Valley to the refined artistry of the Gupta Empire, South Asian sculpture reflects a profound journey of spiritual, cultural, and artistic evolution across millennia.

South Asia is home to some of the world’s most ancient civilizations, with a rich and diverse heritage that spans millennia. Among the most enduring legacies of this region are its sculptures, which offer a window into the religious, cultural, and artistic traditions of various historical periods. From the Indus Valley Civilization to the Gupta Empire, the evolution of South Asian sculpture reflects not only changing artistic techniques but also the profound influence of religious and social transformations over time.

In this article, we will go through the history of South Asian sculpture, beginning with the earliest known works from the Indus Valley Civilization, through the Mauryan and Kushan empires, and culminating in the classical period of the Gupta Empire. Along the way, we will examine how these sculptures served not just as aesthetic creations, but as mediums through which ancient peoples expressed their beliefs, values, and aspirations.

The Indus Valley Civilization

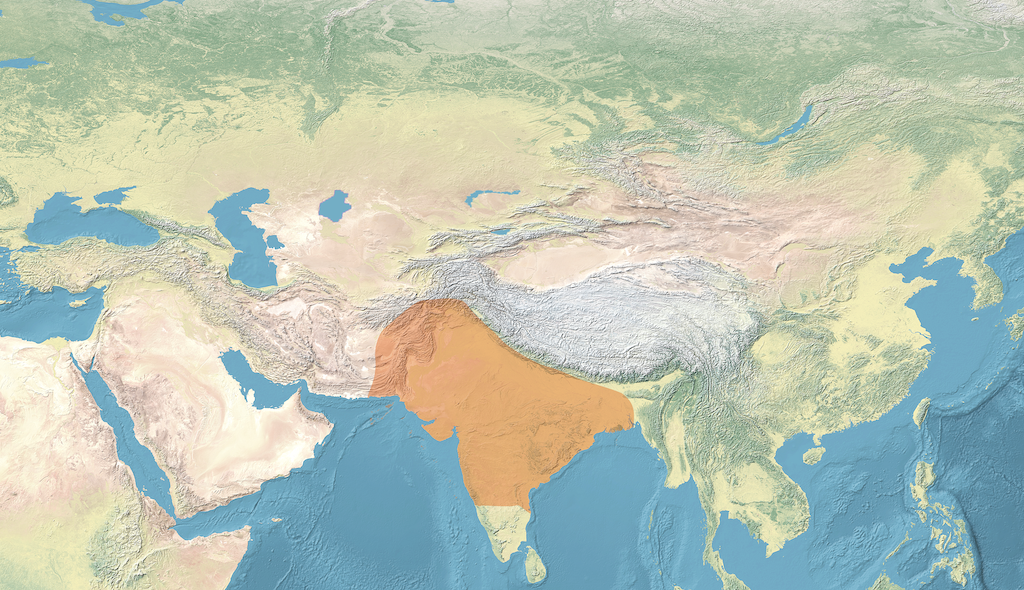

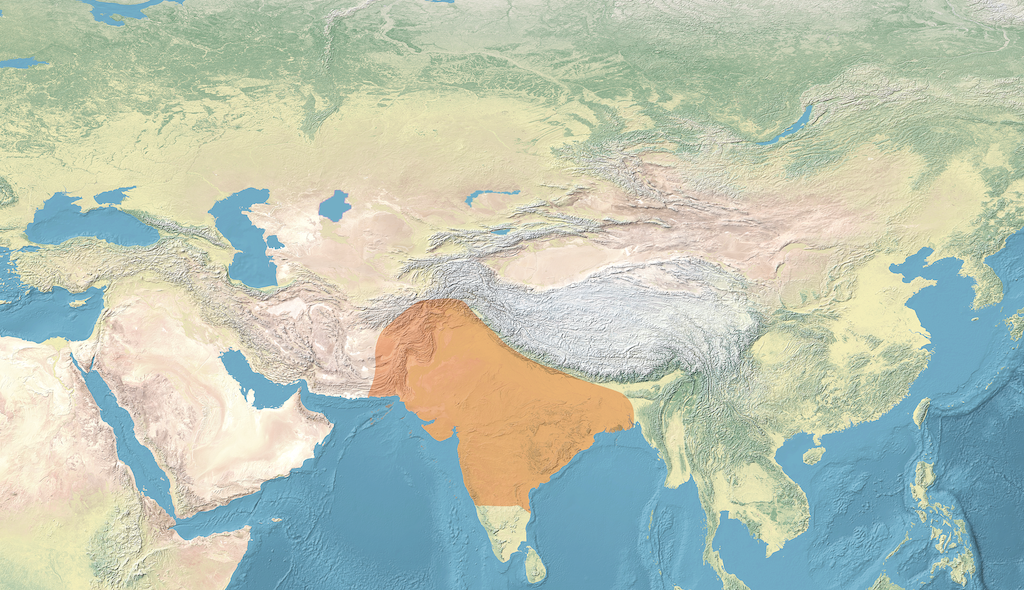

The Indus Valley Civilization (circa 3300–1300 BCE) is one of the world’s earliest urban cultures, flourishing in what is now modern-day Pakistan and northwestern India. While much about this civilization remains shrouded in mystery, its material culture—particularly its art—provides valuable insights into the lives of its people.

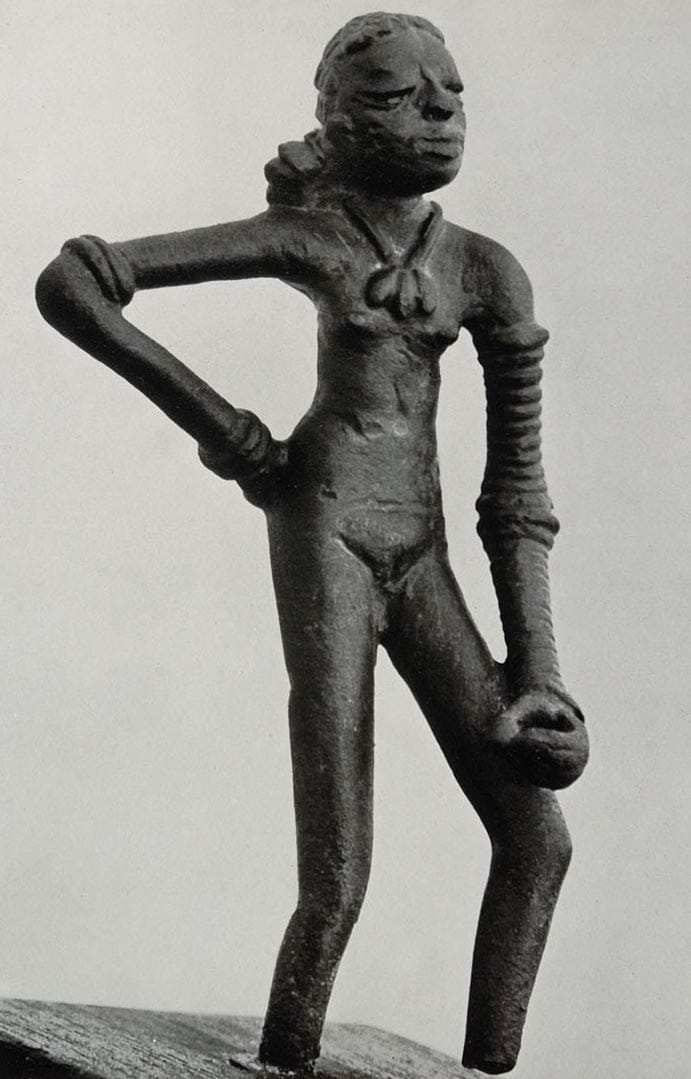

One of the most famous sculptures from this era is the Dancing Girl, a small bronze figure unearthed at Mohenjo-Daro, one of the major cities of the Indus Valley. The Dancing Girl, measuring only about 10.5 centimeters in height, is remarkable for its lively pose and confident expression. Her right hand rests on her hip while her left arm is adorned with bangles, and she stands in a relaxed, almost nonchalant posture. This dynamic representation of a young woman suggests that the artists of the Indus Valley were skilled at capturing human movement and emotion, qualities that would continue to be important in South Asian art for centuries to come.

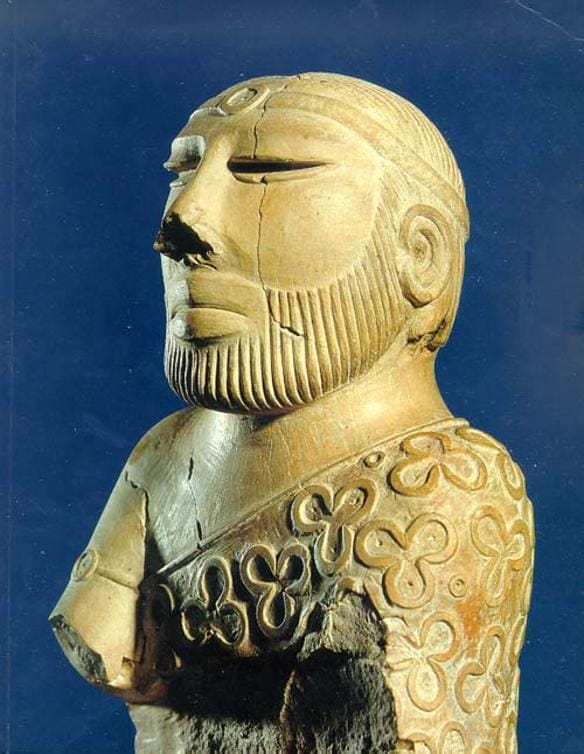

Another significant form of sculpture from the Indus Valley is the Priest-King, a steatite (soapstone) bust of a male figure, also discovered at Mohenjo-Daro. The figure’s dignified appearance, with a carefully groomed beard and elaborate headband, has led scholars to speculate that it may represent a ruler or high priest. While the true identity of the figure is unknown, the Priest-King demonstrates the advanced craftsmanship and attention to detail that characterized Indus Valley sculpture.

The sculptures of the Indus Valley Civilization are typically small and portable, suggesting they may have been used in domestic or ritual contexts rather than as monumental public art. However, they reveal a highly developed artistic tradition that set the stage for later developments in South Asian sculpture.

The Mauryan Empire

Following the decline of the Indus Valley Civilization, South Asia experienced a long period of cultural and political fragmentation. It was not until the rise of the Mauryan Empire (circa 322–185 BCE) that a new era of large-scale, monumental sculpture began to emerge. Under the leadership of figures such as Chandragupta Maurya and his grandson Ashoka, the Mauryan Empire united much of the Indian subcontinent and ushered in a period of prosperity and artistic innovation.

One of the defining characteristics of Mauryan sculpture is its use of polished stone, a significant departure from the terracotta and bronze works of the Indus Valley. This transition to stone allowed for the creation of larger, more durable works, many of which were associated with the spread of Buddhism.

Ashoka, in particular, is credited with promoting the construction of monumental stone pillars known as Ashokan Pillars. These pillars, which were erected across the empire, were inscribed with edicts promoting Buddhist teachings and ethical governance. At the top of many of these pillars sat finely carved capitals, the most famous of which is the Lion Capital of Ashoka from Sarnath. This capital, now the national emblem of India, features four back-to-back lions standing atop a circular base adorned with symbols such as the wheel of Dharma and a lotus flower. The Lion Capital is a masterful example of Mauryan sculpture, showcasing the precision and sophistication of the period’s artisans.

Another significant sculpture from the Mauryan period is the Yaksha, a type of nature spirit often depicted in early Indian art. The Yaksha figures, typically male, are characterized by their robust, muscular bodies and serene expressions. These sculptures, which were often placed near sacred sites or in association with fertility rites, demonstrate the continued importance of indigenous religious traditions alongside the growing influence of Buddhism.

The Mauryan period represents a turning point in South Asian sculpture, as it marked the beginning of large-scale stone carving and the integration of religious themes into public art. The fusion of artistic skill with spiritual messaging would become a hallmark of South Asian sculpture in the centuries to follow.

The Kushan Empire

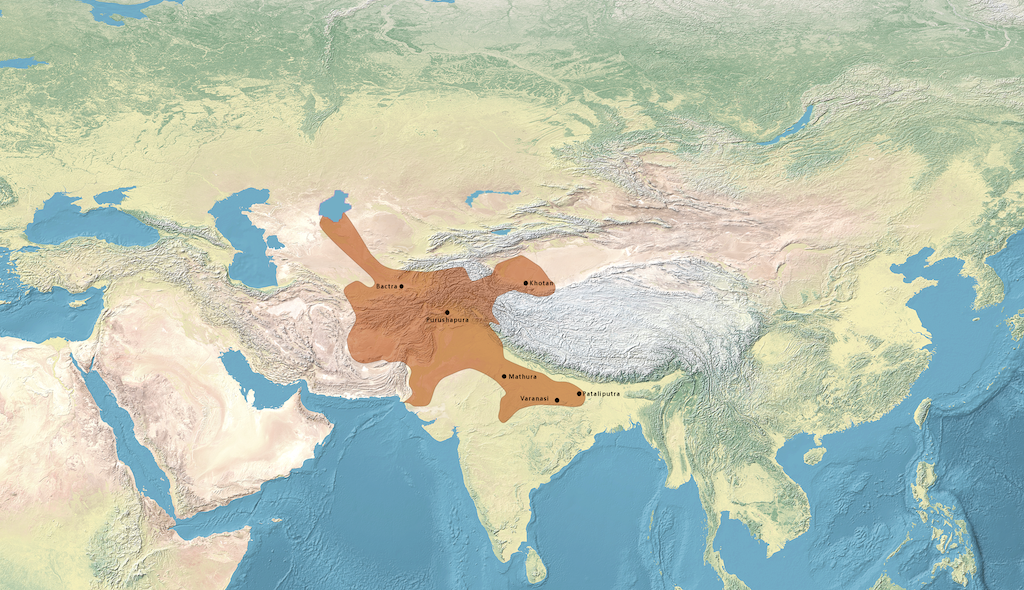

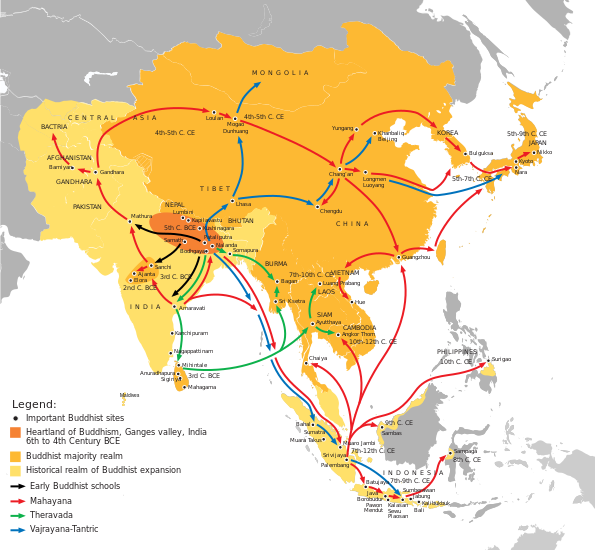

The Kushan Empire (circa 30–375 CE), which emerged in the northern part of the Indian subcontinent, played a crucial role in the development of Buddhist art and sculpture. The Kushans, originally of Central Asian origin, were instrumental in facilitating cultural exchange between South Asia, Central Asia, and the Mediterranean, and their reign saw the emergence of distinct styles of Buddhist iconography.

One of the most significant developments of this period was the creation of the first anthropomorphic representations of the Buddha. Prior to the Kushan period, the Buddha had been represented symbolically, through images such as the Bodhi tree, the wheel of Dharma, or footprints. However, under the Kushans, particularly in the region of Gandhara (modern-day Pakistan and Afghanistan), artists began to depict the Buddha in human form, drawing on influences from Greco-Roman art.

The Gandhara Buddhas, as they are now known, are characterized by their Hellenistic features, including wavy hair, draped robes, and naturalistic proportions. These sculptures often depict the Buddha in meditative or teaching poses, with calm, introspective expressions. The fusion of Greek and Indian artistic traditions in Gandhara resulted in a unique style that had a lasting impact on Buddhist art across Asia.

At the same time, another style of Buddhist sculpture was developing in the region of Mathura, located in northern India. The Mathura Buddhas are distinct from their Gandharan counterparts, featuring more indigenous Indian characteristics, such as rounder faces, fuller bodies, and a greater emphasis on symbolism. For example, the Buddha’s urna (a dot on the forehead representing spiritual insight) and ushnisha (a topknot symbolizing enlightenment) are more prominently displayed in Mathura sculptures.

Together, the Gandhara and Mathura schools of sculpture laid the foundation for Buddhist art in South Asia and beyond. The Kushan period saw the standardization of the Buddha’s image, which would become a central motif in the artistic traditions of countries as diverse as China, Japan, Thailand, and Sri Lanka.

The Gupta Empire

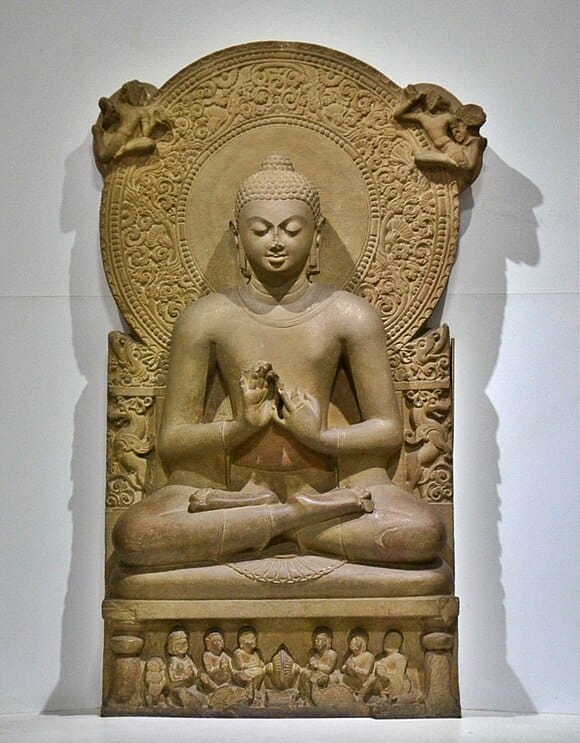

The Gupta Empire (circa 320–550 CE) is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of India, and for good reason. Under the Gupta dynasty, South Asia experienced a flourishing of art, literature, science, and philosophy. In the realm of sculpture, the Gupta period is characterized by a refinement and classicism that would influence Indian art for centuries.

Gupta sculptures are known for their idealized forms, graceful proportions, and serene expressions. This period saw the continued development of Buddhist art, as well as the rise of Hindu sculpture, reflecting the increasing prominence of Hinduism in South Asia.

One of the most famous examples of Gupta sculpture is the seated Buddha from Sarnath, dating to the 5th century CE. This sculpture, made of sandstone, depicts the Buddha in the dharmachakra mudra, or “wheel-turning” gesture, symbolizing his first sermon at Sarnath. The figure is characterized by its smooth, flowing lines, balanced proportions, and a sense of calm detachment. The Gupta artists achieved a delicate balance between naturalism and idealism, creating figures that were both lifelike and spiritually transcendent.

In addition to Buddhist art, the Gupta period also saw the creation of remarkable Hindu sculptures, particularly of deities such as Vishnu, Shiva, and Durga. The Vishnu Anantasayana (Vishnu reclining on the serpent Ananta) is a notable example, depicting the god Vishnu in a relaxed pose, floating on the cosmic ocean. This sculpture, carved in high relief, demonstrates the Gupta artists’ ability to convey complex narratives and divine symbolism through graceful, dynamic figures.

The Gupta period represents the zenith of classical Indian sculpture, a time when artists perfected the techniques and forms that had been evolving for centuries. The emphasis on harmony, balance, and spiritual content in Gupta art would influence not only later Indian art but also the art of Southeast Asia.

The Legacy of South Asian Sculpture

From the small, portable figures of the Indus Valley Civilization to the monumental stone carvings of the Gupta Empire, South Asian sculpture has evolved over thousands of years, reflecting the changing religious, cultural, and political landscape of the region. Each period brought with it new innovations and artistic styles, while maintaining a deep connection to the spiritual and symbolic traditions that define South Asian art.

The legacy of these ancient sculptures continues to resonate today. Many of the forms, techniques, and iconography developed in ancient South Asia have influenced art across Asia, from the Buddhas of China and Japan to the Hindu temples of Cambodia and Indonesia. Moreover, the principles of balance, harmony, and spiritual expression that characterize South Asian sculpture remain central to the region’s artistic identity.