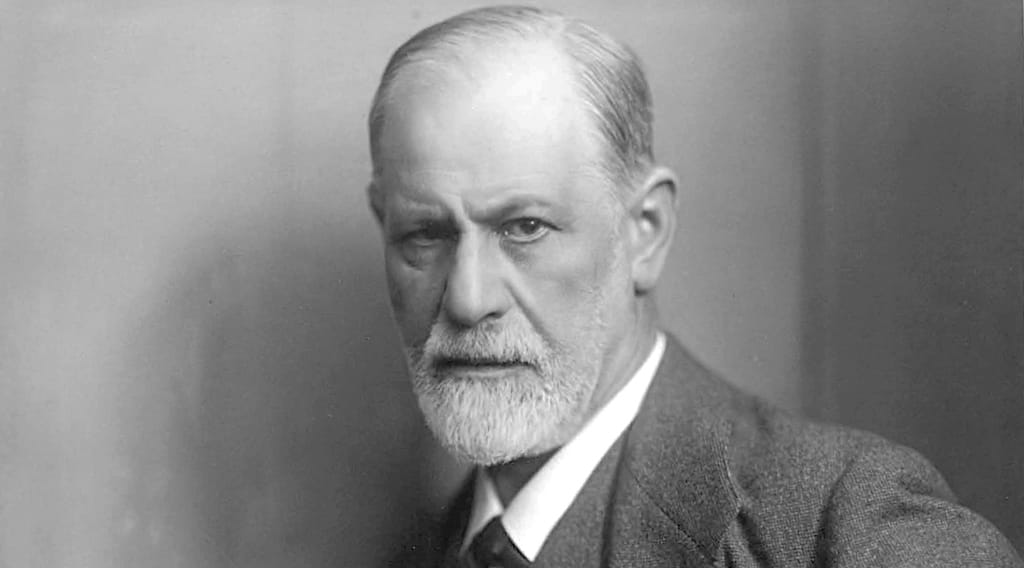

Sigmund Freud: Pioneer of the Unconscious

Explore how Sigmund Freud’s revolutionary theories on the unconscious mind shaped art movements from Surrealism to contemporary practice, revealing the hidden layers behind creativity and the symbolic language of dreams, desire, and conflict.

When painters push pigment across canvas or sculptors coax form from marble, they are not merely arranging shapes and hues. According to Sigmund Freud, the well-spring of every brushstroke lies far beneath conscious intention, in a labyrinth of dreams, desires and half-remembered childhood scenes. Though Freud was trained as a neurologist and never brandished a palette knife, his influence on modern art is profound. From Surrealism’s dreamscapes to Tracey Emin’s confessional installations, the Viennese doctor’s ideas have been a quiet companion in the studio for more than a century.

The Early Years

Born in 1856 in the Moravian town of Freiberg, Freud moved with his Jewish family to Vienna at the age of four. An exceptional pupil, he read Shakespeare in the original before he was ten, and his facility with language shaped his later theorising: Freud never separated science from narrative. While dissecting eels and tracing nerve fibres at the University of Vienna, he was equally enchanted by Goethe and Sophocles. This dual allegiance—to the microscope and to myth—would become the signature of psychoanalysis: clinical observation wedded to storytelling.

After medical school Freud embarked on laboratory research in neuro-anatomy, but financial pressures pushed him towards clinical practice. In 1885 he studied in Paris under Jean-Martin Charcot, whose theatrical demonstrations of hypnotised hysterics convinced Freud that neurological symptoms could originate in the mind, not the body. Returning to Vienna, he and colleague Josef Breuer treated the celebrated “Anna O.” with the “talking cure”. Breuer’s patient discovered that narrating the origins of her ailments—rather than being probed with instruments—relieved them. Freud grasped the radical implication: words themselves could heal.

The Invention of the Unconscious

Freud’s great leap was to insist that consciousness occupies only a sliver of mental life. Beneath it churns the unconscious, a realm teeming with forbidden wishes, traumatic memories and primal conflicts. Because these contents are intolerable to the waking ego, they find indirect expression—as dreams, slips of the tongue, compulsive habits or neurotic symptoms. The analyst’s task is to decode that symbolic language and liberate the trapped affect.

This vision reconfigured the self as layered and conflict-ridden. It also handed artists a new subject: the invisible drives shaping visible form. If painting once strove to copy the external world, now it could chart the inner one.

Dreams as Royal Road to Art

In 1900 Freud published The Interpretation of Dreams, calling dreams “the royal road to the unconscious”. He described them as wish-fulfilments disguised through condensation, displacement and visual punning. For painters and poets, the manifesto was irresistible. Why render what the eye already sees when the mind, in sleep, stages spectacles of impossible juxtapositions?

Max Ernst, Salvador Dalí and René Magritte read Freud avidly. Dalí dubbed himself a “paranoiac-critical” method actor, painting melting clocks and spectral giraffes pulled straight from dream logic. Magritte’s apples filling rooms or pipes that are not pipes echo Freud’s idea that representation is never straightforward, always riddled with desire and denial.

Yet Freud himself kept a wary distance from avant-garde art. Visiting an exhibition in 1938, the 82-year-old analyst remarked that surrealist canvases resembled the work of his patients—an observation tinged with both pride and irony.

The Oedipus Complex and Narrative Archetype

No concept earned Freud more fame—or ridicule—than the Oedipus complex. Drawing on Sophocles’ tragedy, he proposed that between three and five years old, a boy feels erotic longing for his mother and rivalry toward his father; a girl, conversely, experiences “penis envy” and turns her desire toward the father. Whether artists accept or dismiss this schema, its narrative power is undeniable.

Modern literature bristles with Freudian family dramas, and visual art likewise mines parent-child tension: consider Egon Schiele’s contorted nudes or Louise Bourgeois’ towering spider Maman, a tribute to her seamstress mother. Even abstract painters, such as Jackson Pollock, spoke of “breaking” from artistic forefathers—an echo of Oedipal rebellion on canvas.

Repression and the Aesthetic of the Fragment

Freud argued that repression forces unacceptable thoughts underground, yet they return in disguised fragments. This notion resonated with artists who began to favour collage, montage and fractured perspective. Cubism, for example, shatters objects into facets as though revealing multiple viewpoints at once—much like a dream’s composite images. Hannah Höch’s photomontages splice newspaper clippings into unsettling hybrids; they feel less like quiet portraits and more like repressed memories bursting through.

The Pleasure Principle, Thanatos and the Avant-Garde

Freud’s later work introduced the “death drive” (Thanatos), positing a counterforce to Eros, the life instinct. The dialectic between creation and destruction captured the imagination of Dadaists and Expressionists haunted by World War I. Otto Dix’s lurid war scenes and George Grosz’s grotesque caricatures mirror a civilisation swinging between pleasure and annihilation.

The Couch and Its Critics

Psychoanalysis spread quickly, aided by Freud’s charismatic case studies. Yet from the outset it attracted scepticism. Behaviourists dismissed the unconscious as unobservable; feminists criticised penis envy as patriarchal projection; philosophers accused Freud of unfalsifiability. Even so, his lexicon—libido, ego, defence mechanism—permeated everyday speech.

For artists, the critique was less important than the licence Freud granted: to dig where reason hesitates, to trust accident, to embrace ambiguity. Surrealist automatic writing, Abstract Expressionist action painting and contemporary performance art all echo Freud’s faith in spontaneous expression.

Post-Freudian Currents in Contemporary Art

While few twenty-first-century artists pledge allegiance to psychoanalysis, its traces remain:

- The archive fever of photographers like Christian Boltanski, cataloguing lost childhoods, reflects Freud’s insistence on memory’s persistence.

- Jenny Holzer’s scrolling LED truisms—“PROTECT ME FROM WHAT I WANT”—translate unconscious desire into public spectacle.

- In video art, Ragnar Kjartansson’s looping performances mimic repetition compulsion, Freud’s idea that trauma replays itself until understood.

Even abstraction owes Freud a debt. He argued that the psyche converts emotion into image; modern artists convert image back into pure feeling, closing the circle.

Freud’s Own Relationship with Art

Contrary to myth, Freud was no philistine. He collected over 2,000 antiquities—Egyptian figurines, Greek vases, Roman busts—arranged in his consulting room like silent co-analysts. Patients on the couch faced rows of gods and heroes, reminders that personal neurosis partakes in mythic drama. Freud wrote essays on Michelangelo’s Moses and Leonardo’s Mona Lisa, treating masterpieces as case studies. Though art historians bristle at his speculative biographies, Freud’s method—reading images as encrypted confessions—set a precedent for iconographic analysis.

Legacy: From Clinic to Studio

Today, neuroscientists question Freudian metapsychology, yet artists continue to plunder his storehouse. Why? Because art, like psychoanalysis, believes surface is never the whole story. Both disciplines hinge on interpretation, on coaxing sense from symbols. The studio, like the couch, is a space where time slows and association roams, where fragments are rearranged until a hidden pattern emerges.

In Britain, this lineage threads from Francis Bacon’s screaming popes—flesh smeared into existential angst—to Sarah Lucas’ bawdy assemblages of tights and melons, jokily exposing the libido. Lucian Freud, the founder’s grandson, approached portraiture with forensic intensity, peeling back skin in thick impasto as though searching for the sitter’s unconscious.

Why Freud Still Matters to Art

Freud’s detractors often note that his clinical evidence was scant and his worldview steeped in Victorian mores. Yet as a cultural catalyst he remains unrivalled. He shifted the artistic gaze inward, from the optic nerve to the nerve of desire. He supplied a vocabulary for what resists articulation—dream imagery, slips, symptoms—and thus expanded art’s remit.

When viewers stand before a Dalí canvas or a Bourgeois sculpture, they do not need to recite Beyond the Pleasure Principle to feel its pulse. Freud’s gift was to show that beneath the calm of daylight lies a nocturnal theatre, and that entering it—whether by free association or fearless making—can transform private torment into shared meaning.

Artists will always raid philosophy and science for metaphors, but Freud offered more: a method of excavating the self. In an era when algorithms chart behaviour in real time, the Freudian unconscious may seem quaint. Yet its insistence on depth, ambiguity and conflict is a salutary reminder that human creativity still dances to rhythms no data set can predict.

Thus, for any painter mixing colours at midnight, or poet wrestling with a line that keeps slipping from view, Freud remains a silent collaborator. He whispers that the obstacle may be the clue, the accident the intention, the fragment the map. And in that subterranean whisper, art finds inexhaustible possibility.