'Shrines' at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke: Abul Hisham’s Phantasmagorical Sanctuaries

In 'Shrines', Abul Hisham reinvents his practice with spectral sanctuaries built from absence and memory. Blending Indian classical traditions with European influences, his fragmented figures and architectures transform ruins into spaces of fragile devotion and resonance.

When Kerala-born artist Abul Hisham (b. 1987, Thrissur) unveiled Shrines, his third solo with Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, it marked not just another chapter in his career but a profound departure. Known for transmuting Safavid, Mughal, Rajput, and Deccani motifs into uncanny, expressionist vocabularies, Hisham has long stood at the crossroads of history and contemporary disquiet. With Shrines, however, the artist moves beyond incantation into revelation. This is Hisham transformed, as much in medium as in mood, working from fragments and absence to create sanctuaries that are at once spectral and resonant.

From Recitation to Renewal

Hisham’s previous exhibition in India, Recitation (2019), was built from pastel-on-paper works that echoed the cadences of repetition and prayer. Those paintings bore witness to systems of knowledge, memory, and spirituality, anchoring themselves in rhythm and reflection. By contrast, Shrines spirals into the ineffable, confronting the viewer with works that feel both heavier and more elusive.

The artist traces this shift back to his residency at the Rijksakademie van Beeldende Kunsten in Amsterdam. “For more than a decade, I had been working almost exclusively with pastels, but moving to Amsterdam felt like the right moment for a new beginning. I didn’t want to return to a medium I already knew so well; both physically and emotionally, I needed to start afresh,” he recalls.

At the Rijksakademie, he began by making very small paintings on wood, works no bigger than a matchbox, rather than the large-scale pastels he was used to. “Every day I would paint, almost as a way of documenting my thoughts or responding to the images that came to me. I never allowed myself to stop. It became a period of constant experimentation—with images, materials, and mediums,” he explains.

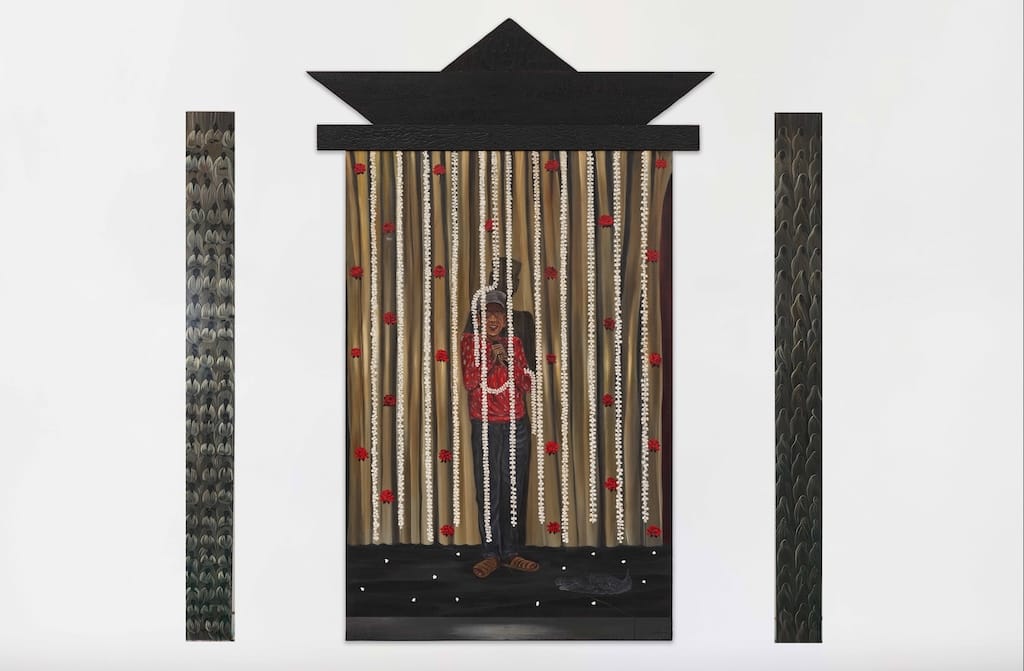

This experimentation changed not just the surface of his works, but the very way he understood painting. “Earlier I was more interested in the idea, narration, and execution, and the act of drawing was an integral part of the process. Now I am more drawn towards the atmosphere, balance, and emotional qualities of a painting. Acrylic, casting powder, even wood—these were not just mediums but thresholds. They introduced weight, tactility, a kind of resistance that pastel did not. What emerged was not a break, but a conscious act of renewal. A movement from dust to weight, from affirmation to atmosphere, from narration to presence.”

The Sacred as Atmosphere

The title of the show gestures to the idea of a sanctuary, yet Hisham resists any easy or literal interpretation of the sacred. “For me, the sacred is never a fixed image or a doctrine—it is more like an atmosphere, something that hovers and lingers,” he says.

The exhibition text speaks of Shrines as a “sanctuary built from absence,” a phrase Hisham immediately recognises as resonant with his own experience. “The works are not about recreating a literal shrine or a ritual site, but about evoking that residue of presence we carry within us, even when the source has been lost. Absence plays a central role, because absence is often where memory becomes most vivid. A wall, a fragment, a half-erased figure—these are not empty, but charged with what cannot be fully seen. I think the sacred emerges precisely in this tension, between concealment and revelation, between what survives and what has been erased.”

Faces Erased, Identities Multiplied

Hisham’s figures often appear partly effaced, partly remade—neither fully themselves nor wholly absent. This play between recognition and distortion is deeply intentional. “Removing the face of somebody is, to me, a deeply political act,” he notes. “It is a response to the times we live in, where images of individuals are erased or defaced, often on the basis of caste or religion, where the act of scratching out or covering a face becomes a way of denying identity and presence.”

For Hisham, this act is not merely destructive but revelatory. “I am interested in that fragile moment when a figure is no longer fully itself—when it slips between being recognised and being lost. We never remember someone in perfect detail; there are always gaps, distortions, erasures. By partly effacing or remaking a figure, I try to hold it in that in-between state: close enough to feel familiar, yet distant enough to remain unsettled. A face without features, or a body partly erased, can hold many lives, not just one.”

This in-betweenness, between recognition and estrangement, presence and absence, runs through Shrines, shaping its uneasy but magnetic atmosphere.

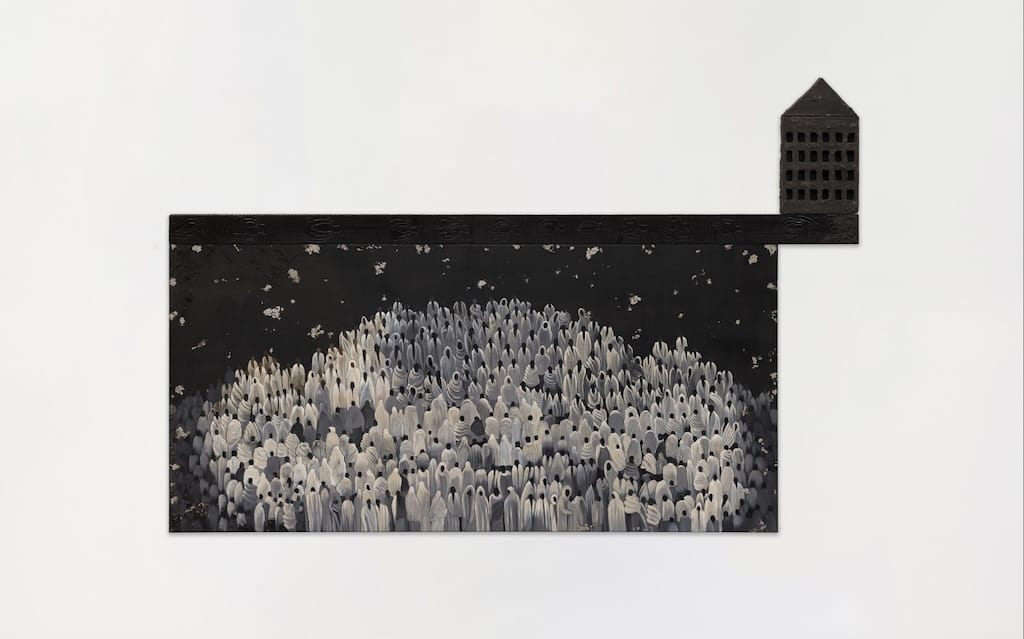

Anchored in Tradition, Open to Encounter

Hisham’s practice has long drawn from Safavid, Mughal, Rajput, and Deccani repertoires, which remain visible even in this transformed body of work. “These classical traditions remain deeply embedded in my practice; they have never disappeared,” he insists. “If you look closely at the way I paint and repeat imageries—especially through small, clustered figures—you can clearly trace the techniques of Mughal painting and even Buddhist frescoes. That rhythm of repetition and detail is something I continue to carry forward.”

Rather than loosening his ties to these traditions, he has sought to expand them through new encounters. “It is not about loosening their hold. On the contrary, it is about holding them firmly, while also allowing them to expand into new encounters. With Shrines, this has evolved into what I see as an Indo–Western approach. It has the sensibility of Indian classical painting traditions, yet brings them into dialogue with the European traditions I came to know more closely during my time in Europe.”

This dialogue is not merely stylistic. It signals an ongoing negotiation between memory and displacement, origin and encounter, anchoring and expansion.

Architecture, Body, Fragment

The presence of architectural fragments, walls, arches, pillars, runs throughout Shrines. These are never mere backdrops but active participants in the atmosphere of the works. “For me, the body and architecture are very closely connected. Both hold memory, both carry the marks of time, and both can be fragile,” Hisham explains. “In Shrines, the fragments of walls or arches are never just background—they press against the figures, contain them, sometimes even trap them.”

He insists on calling them fragments precisely because neither body nor architecture appears whole. “Like memory, they come to us in pieces. A figure near a wall, a crowd squeezed into a narrow frame, a small ritual gesture—these are fragments, but they still carry presence. Architecture gives weight and shelter, while the body brings breath and vulnerability. Together they create the atmosphere of the shrine—something broken, but also remade.”

This imagined architecture, composed of both ruins and gestures, recalls the fragility of memory itself: incomplete, yet luminous in its incompleteness.

Between Thrissur and Amsterdam

Although Hisham now lives and works in Amsterdam, his native Thrissur remains indelible. “Thrissur remains inscribed in me—its rituals, memories, and landscapes—but the shift of place has brought a new clarity. Being away from home allows me to see what I carry with me more sharply: my origins, beliefs, traditions, even the images that once felt too familiar to notice,” he reflects.

Distance has not distanced him from his roots; it has refined them. “Distance doesn’t erase them, it distills them,” he observes. The move to Amsterdam has also widened his frame of reference: “Here I also encounter a wide spectrum of practices—European classical painting, but also diverse indigenous art. This interaction has widened my vocabulary, making me more attentive to atmosphere, balance, and the emotional registers of colour, while also reminding me of the rhythms of repetition and devotion in Indian and Islamic traditions.”

This distance, paradoxically, has become a space of deep inward travel. “Distance has opened a room within me, a space for inward travel, where I find myself revisiting what once felt certain—my origins, my beliefs, and the patterns of memory I carry. This questioning is not a departure but a deepening. So the move has not shifted my concerns with power, memory, or belief; it has given me new ways of approaching them—less through narration, and more through atmosphere, presence, and the fragile tension between what is revealed and what remains withheld.”

A Liturgy of Fragments

Shrines is less an exhibition than an atmosphere of devotion. Totemic pillars, architectural shards, phantasmagorical figures, and ritual gestures come together to form what writer Shankar Tripathi has called “a shrine without centre.” For Hisham, this absence is not a void but a fragile aura in which the sacred persists. “Absence plays a central role, because absence is often where memory becomes most vivid,” he reminds us.

Hisham’s work evokes childhood visits to sacred sites, blending the glow and incense of memory with a language of rupture and reinvention. His shrines, built from fragments, offer not permanence but persistence, where ruin becomes devotion. Shrines reveals an artist who carries tradition into new encounters, turning absence into presence and transforming remnants into sanctuaries. Walking through Shrines is to experience a liturgy of fragments, where memory and the sacred persist in what remains.

'Shrines' by Abul Hisham is on view until 23 October at Galerie Mirchandani + Steinruecke, 1st Floor, C.R. Tower, D-58, Defence Colony, New Delhi 110024.