Sculpting the Future: L.N. Tallur on Art, Innovation, and Society

Through a unique blend of traditional craftsmanship and cutting-edge technology, artist L.N. Tallur addresses contemporary anxieties—balancing irony and depth to provoke thought on themes like environmental decay, technological evolution, and societal fears.

Internationally celebrated contemporary artist L.N. Tallur challenges conventional narratives with a practice that intertwines tradition, technology, and cultural critique. Born in rural Karnataka, Tallur’s artistic journey has spanned continents, with his education and experiences across India and the UK profoundly shaping his worldview. His works—ranging from monumental public sculptures to intricate gallery pieces—provoke thought on pressing global issues such as environmental depletion, technological obsolescence, and societal anxieties.

Known for his inventive use of materials, Tallur merges ancient techniques like Dhokra casting with modern processes like 3D printing, creating works that are as thought-provoking as they are visually striking. His ability to embed profound themes within playful, ironic compositions makes his art accessible yet deeply resonant. In this interview, Tallur delves into the inspirations behind his works, his creative process, and his reflections on the evolving role of art and technology in a rapidly changing world.

Preliminary explorations of L.N. Tallur’s artworks, showcasing the evolution of his concepts through sketches, digital renderings, and prototypes before their final realization

Nikhil Sardana: Your work often juxtaposes traditional craftsmanship with contemporary materials and themes. How do you approach this blend, and what drives your choice of materials?

L.N. Tallur: Currently, I am exploring the ancient technique of Dhokra casting, where beeswax strings are coiled to create patterns for the final object. Interestingly, this process parallels 3D printing, where objects are built through an additive layering method. This fascinating overlap between tradition and technology often sparks ideas for themes. At other times, the themes themselves guide my choice of medium.

For example, the concept of Purush Mriga—a mythological creature, half-man and half-animal, known to run as fast as human thought—resonates with contemporary ideas of Artificial Intelligence. To bring this idea to life, I used plywood, a material composed of layers from multiple trees, each carrying the essence or ‘information’ of its source. I named this work Data Mining.

Interference Fringe by L.N. Tallur

NS: Growing up in rural Karnataka and studying across India and the UK, how have your diverse experiences shaped your artistic vocabulary and worldview?

LNT: Living in different places exposes you to new sights, sounds, tastes, and textures that can be overwhelming at first. However, when you make the effort to understand these nuances, they act as catalysts for artistic thought.

In fact, I’ve designed a workshop called 6th Sense, where participants create sculptures in a completely dark room. This immersive experience blocks one sense—sight—forcing the brain to rewire itself and heighten the remaining senses, such as sound, taste, smell, and touch. This process not only amplifies creativity but also fosters a deeper connection with your surroundings, offering a unique perspective that enriches both artistic vocabulary and worldview.

Glitch Tandav by L.N. Tallur

NS: Themes like technological deterioration and environmental depletion recur in your work. How do you navigate presenting such heavy themes with elements of play and irony?

LNT: Take my recent work Glitch Tandav, for example. It features a green patina on bronze—what is commonly referred to as "bronze disease." This condition results from a chemical reaction between bronze and chlorides, leading to pitting and corrosion. Originally believed to be caused by bacteria, bronze disease is contagious in that it can spread to other cuprous objects if they come into contact.

Shiva Tandava represents both destruction and recreation. In this work, I applied the green patina to arrest the corrosion of the bronze. However, the object appears as though it is succumbing to the disease, symbolizing the paradox of healing and decay.

V+Mana Installation at Kempegowda International Airport, Bengaluru

NS: You’ve created permanent public sculptures at notable locations like Kempegowda International Airport and UPM Circle, Manipal. How does working on public art differ from creating works for galleries or museums?

LNT: When public art includes familiar symbols, it allows viewers to connect more comfortably. For instance, my sculpture V+Mana at Kempegowda International Airport refers to the word Vimana, which means both "aircraft" and the gopuram (tower) of a temple. This duality invites people to think in different directions. The sculpture appears to "float," akin to a Hindenburg balloon, creating a sense of intrigue.

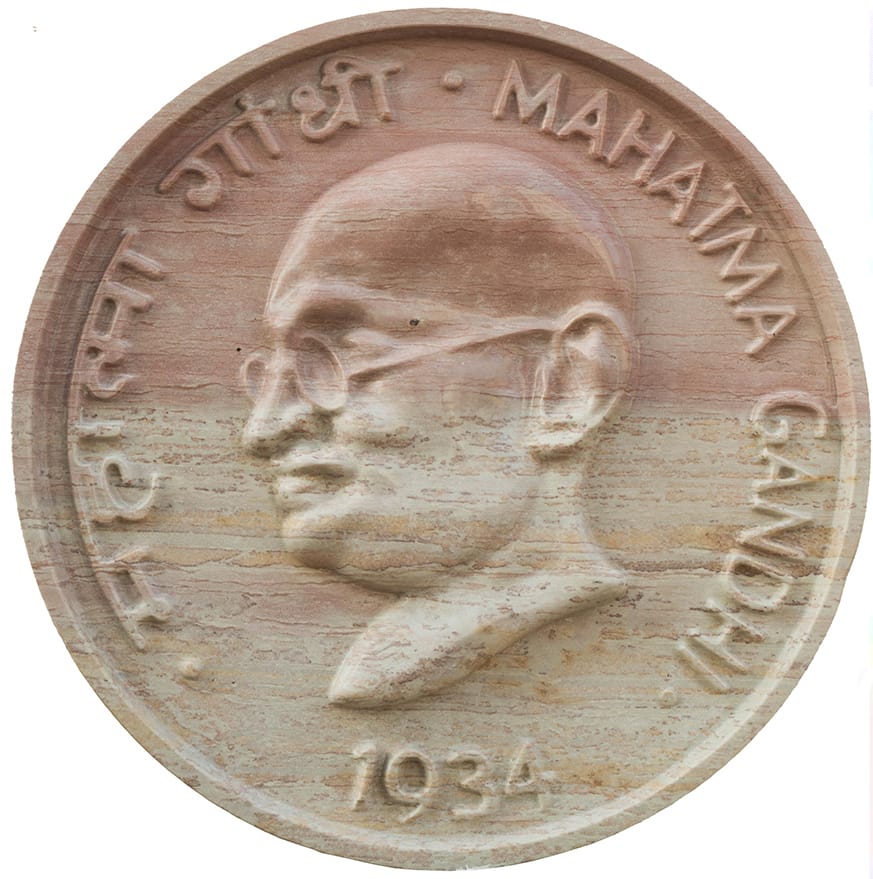

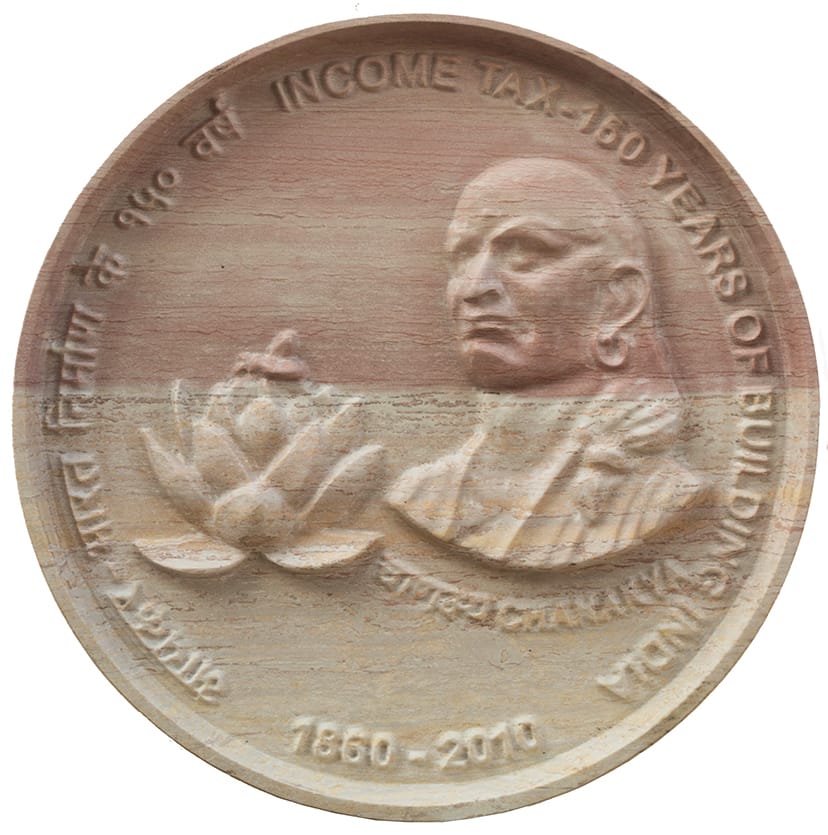

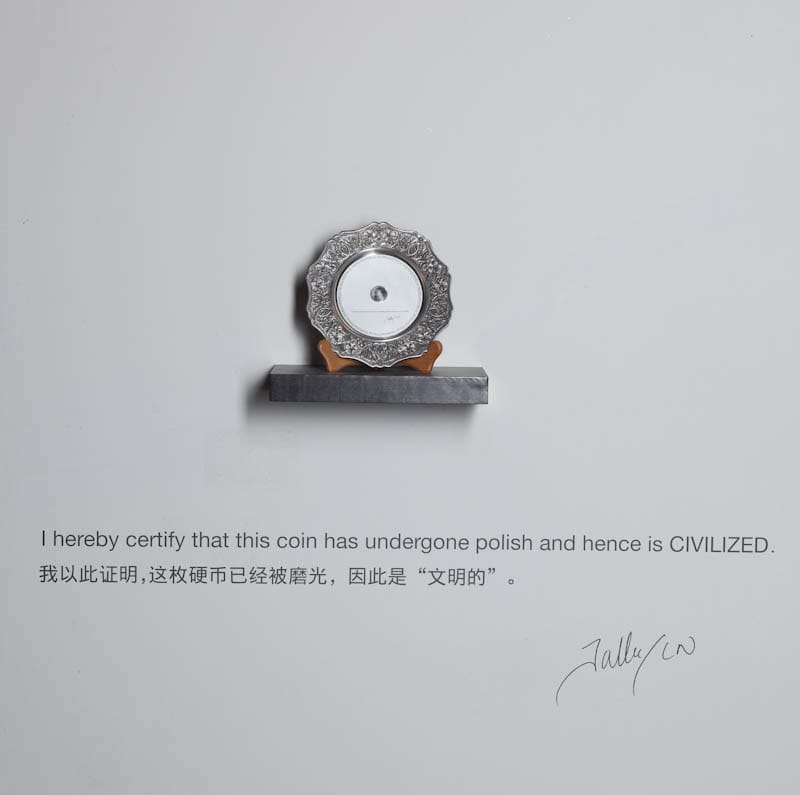

Similarly, at the UPM Circle in Manipal, my sculpture incorporates ancient coins from the region along with modern ones, exploring the history of coin-making methods. The coins appear to balance vertically, creating a magical illusion. The work also references Manipal’s history as the birthplace of Syndicate Bank, Vijaya Bank, and the concept of Pigmy accounts.

Coinage by L.N. Tallur at UPM Circle, Manipal, India. This 27-foot-high sculpture, crafted from seven assorted stones, honours Thonse Upendra Anantha Pai (1895–1956), the visionary who transformed barren Mannapalla into the thriving city of Manipal. Symbolizing trust, vision, and dreams, the artwork celebrates Manipal’s socio-cultural heritage and Pai’s enduring legacy.

NS: Your works often incorporate found objects and damaged materials. What draws you to these elements, and how do they influence the meaning of your pieces?

LNT: I frequently use "yesterday-made antiques," inspired by the thriving industry in India that produces lookalike Chola bronzes. The industrial process of replicating these traditional sculptures—right down to the speed of production and the material recipes—imparts a unique character to the objects.

These absurd industrial products become a fascinating starting point for my art. By recontextualizing these materials, I add layers of meaning to my pieces, highlighting the tension between authenticity and mass production.

Chromatophobia by L.N. Tallur

NS: Interference Fringe, your survey exhibition at Grounds for Sculpture, explored the anxieties of contemporary society. How do you choose which societal issues to address in your work?

LNT: After the 2008 financial recession, which impacted many of my artist friends, money became a dominant topic in conversations. This inspired me to explore money as a theme in my work.

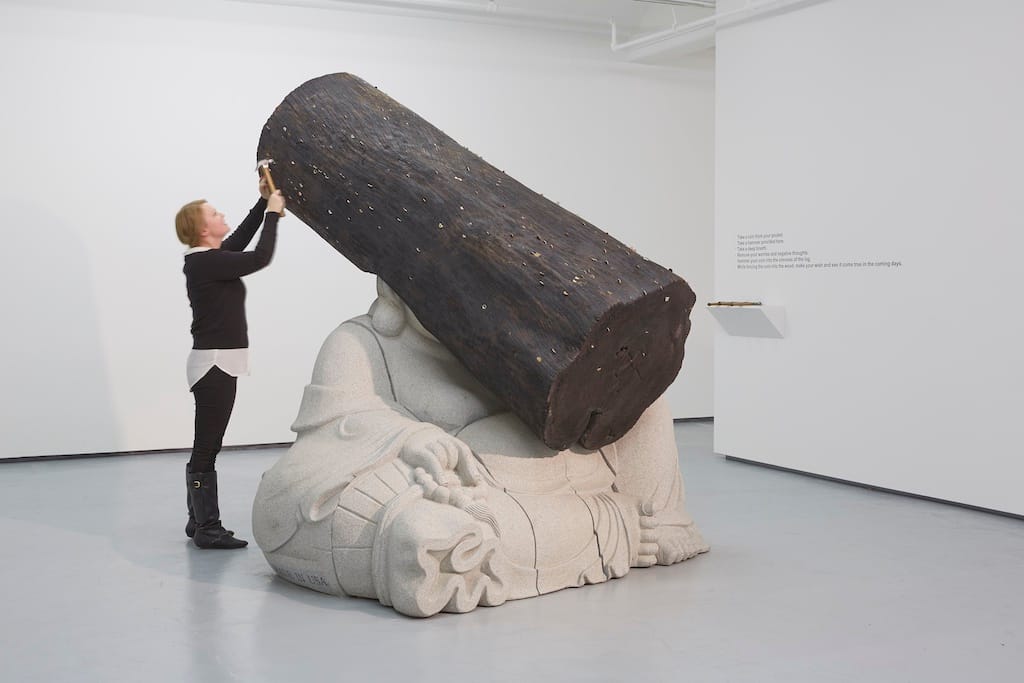

I created a therapy called Chromatophobia, which references the irrational fear of money. In this interactive piece, participants hammer coins onto a wooden log, turning the act into a calming, meditative ritual.

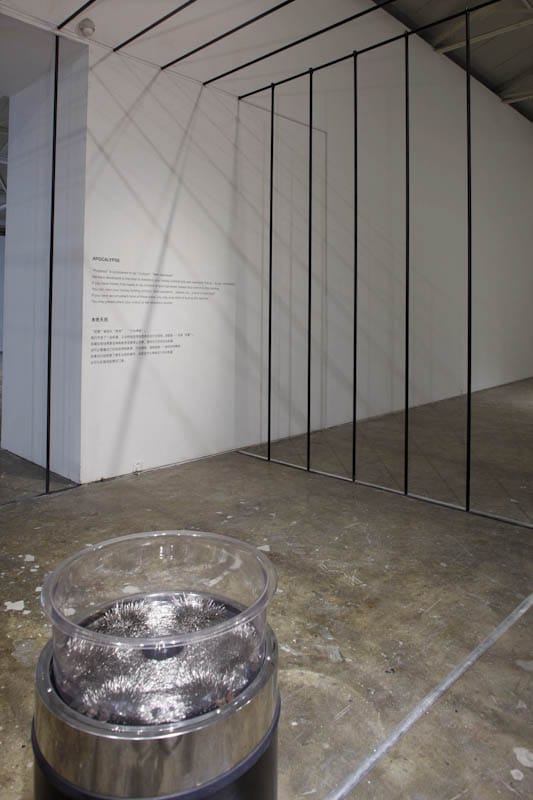

Another piece, Apocalypse, is a coin-polishing machine that gradually erases the coin’s denomination as it polishes. Over time, the coin loses its monetary value, symbolizing the ephemeral nature of wealth.

Apocalypse by L.N. Tallur

NS: Your recent exhibitions, such as Neti-Neti: Glitch in the Code and Data Mining, suggest a focus on digital and technological themes. How do you see the role of technology evolving in art, especially in India?

LNT: Technology is a tool—it amplifies clarity when the artistic vision is well-defined. A knife in a surgeon’s hands can save lives, but the same knife can harm if the intention is malicious.

Unfortunately, many contemporary artists focus on creating the illusion of art rather than genuine expression. This results in "glitches" in objects that once held artistic integrity. Audiences must train their minds and eyes to discern true art.

As technology becomes more accessible, we risk irrelevance if we don’t engage with it meaningfully. However, when used thoughtfully, technology can add profound depth to art.

Data Mining by L.N. Tallur

NS: You’ve exhibited globally across diverse cultural contexts. How does the reception of your work differ in India versus international audiences, and how do these perspectives shape your creative process?

LNT: Interacting with diverse audiences has taught me to focus on my personal experiences and observations while eliminating unnecessary information influenced by mainstream art.

When I stay true to my perspective, my intentions naturally reflect in the work, making it unique. The power of a piece lies in the artist’s involvement, and authenticity transcends cultural boundaries, resonating with audiences everywhere.

Installation view of Neti-Neti: Glitch in the Code