Reimagining Colonial Gardens: An Interview with Amba Sayal-Bennett on 'Dispersive Acts'

Amba Sayal-Bennett's 'Dispersive Acts' explores Mumbai's Rani Baug's colonial history, challenging control and order through her sculptures. In this interview, she discusses resistance, botanical migration, and imperial history's impact on contemporary art.

In her first solo exhibition in India, "Dispersive Acts," British-Indian artist Amba Sayal-Bennett delves deep into the intricate histories of colonial botany and imperial gardens. Presented at TARQ, Mumbai, this new series of sculptures and drawings draws inspiration from Rani Baug, a botanical garden established in the 1860s during British colonial rule. Sayal-Bennett's work is a compelling exploration of how colonial powers exerted control over nature and how these forces are subtly resisted and subverted through natural processes.

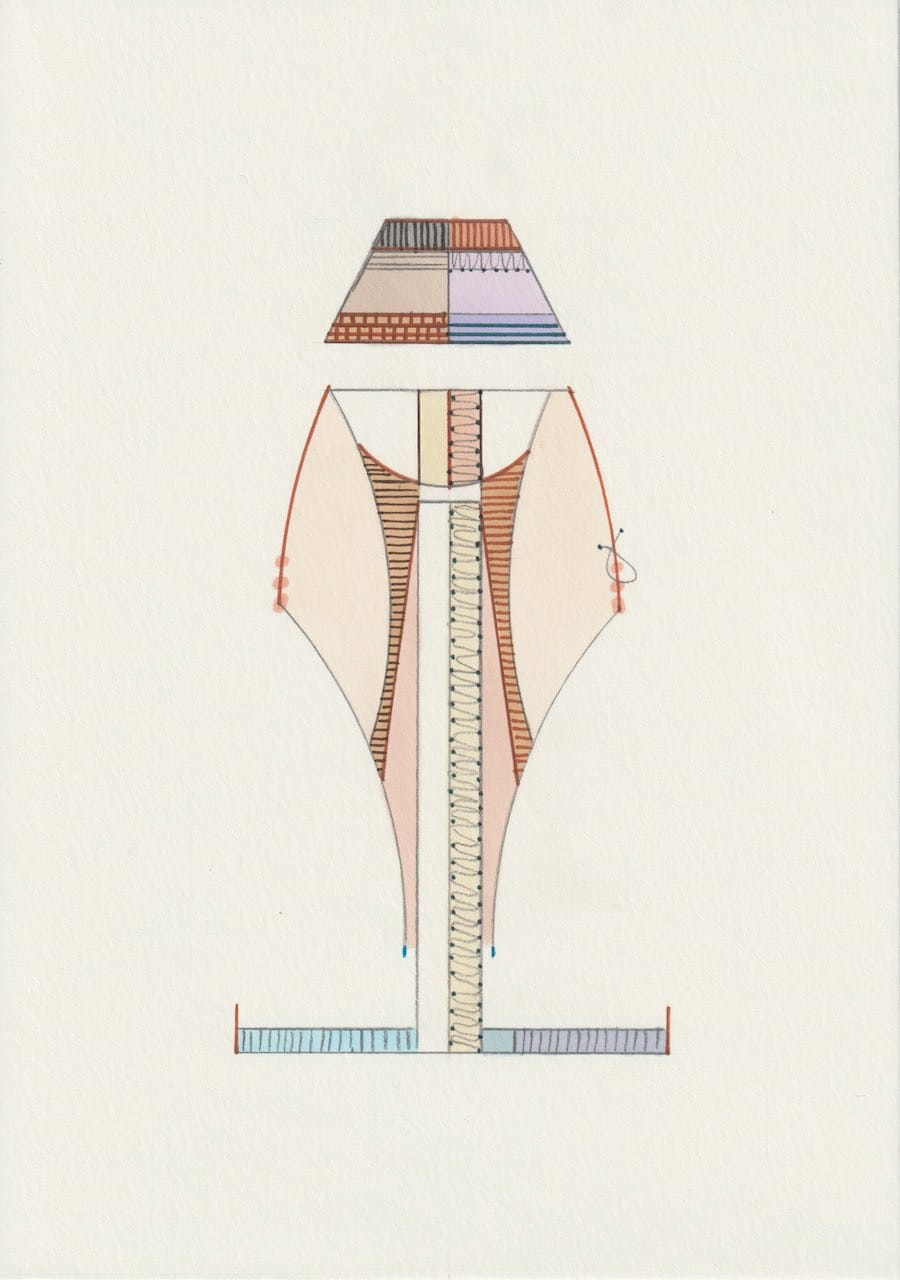

With a background steeped in both artistic practice and academic research, Sayal-Bennett’s work transcends mere aesthetic engagement. She examines the complex interplay between imperial history, botanical migration, and the architecture of control. Through her use of industrial materials like resin and steel, alongside digital design methods, her sculptures evolve in ways that echo the disordered growth of plants, challenging the rigidity of colonial structures.

In this interview, Sayal-Bennett discusses the themes and inspirations behind "Dispersive Acts," her unique approach to blending historical research with contemporary art, and the significance of showcasing this work in Mumbai—a city with its own rich fabric of colonial and post-colonial narratives.

Serenade Team: "Dispersive Acts" is your first solo exhibition in India. How does it feel to bring your work to Mumbai, and what does this location add to the narrative of the exhibition?

Amba Sayal-Bennett: It is very exciting to show my work in Mumbai, as this location is central to the focus of the exhibition. While developing "Dispersive Acts," I researched the history of a botanical garden in Mumbai called Rani Baug, formerly known as Victoria Gardens. The exhibition explores this garden as both a colonial archive and a site of resistance.

ST: Your work often explores themes of colonialism and the migration of botanical matter. Could you elaborate on how the history of Rani Baug influenced the pieces in this exhibition?

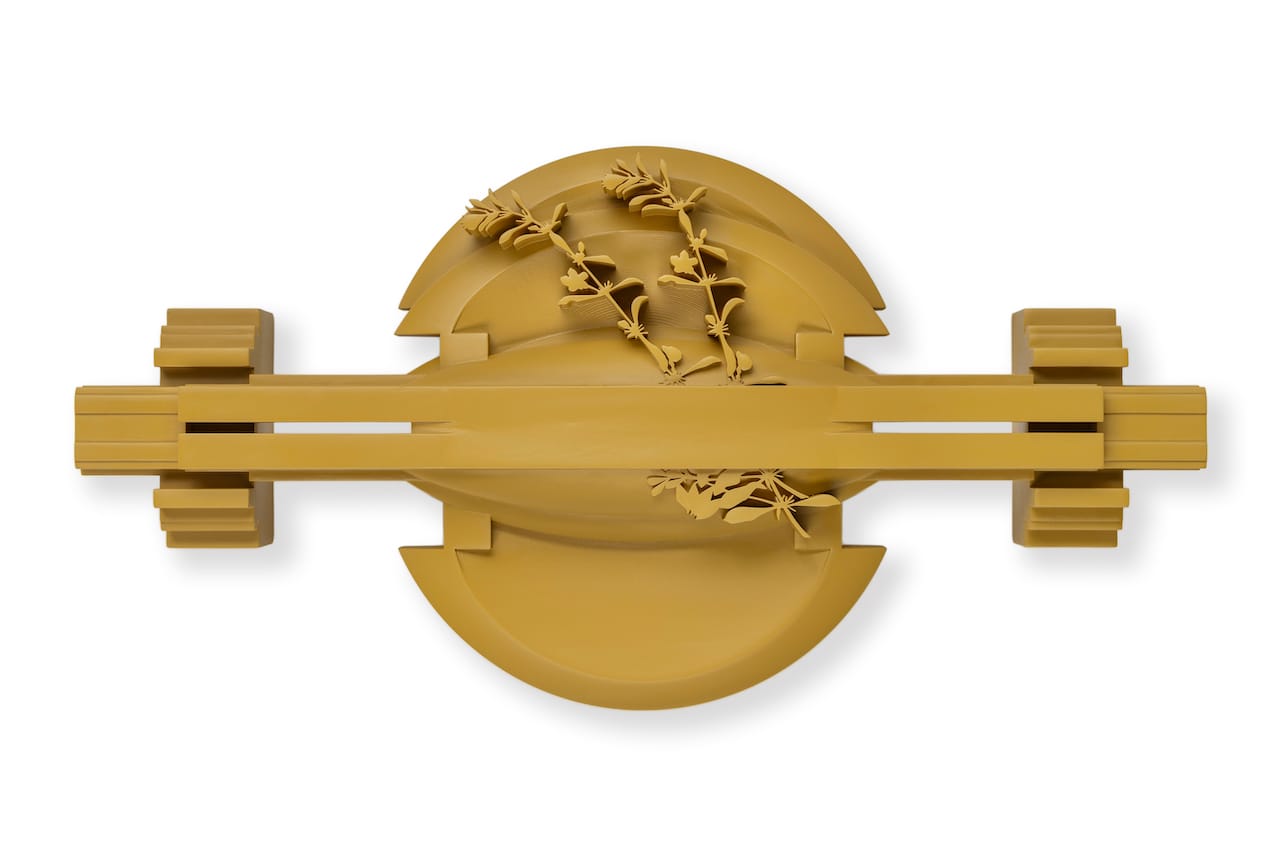

ASB: Rani Baug was established in the 1860s, and I became intrigued by its role as an imperial garden and a laboratory of empire. During this period, the Victoria Gardens served as a museum for British enlightenment, with plants imported from parts of Asia, Africa, and the Americas to be catalogued there. The imposition of the Victorian English garden structure onto the site reflected a Eurocentric worldview, with a layout designed along a clearly defined axis and radiating pathways. I began considering how these rigid pathways symbolized a separation that allowed nature to be observed—a relationship central to colonial practices. I also thought about how plants might have resisted this classic English garden structure through seed dispersal or by branching out over borders. These methods of resistance are reflected in the works, where botanical forms are dispersed across different sculptures and floral elements meld into and overgrow their structures.

ST: You incorporate industrial materials like resin and steel in your sculptures. How do these materials help convey the themes of control and subjugation in colonial gardens?

ASB: I wanted the botanical elements in the works, made through precise machine production, to allude to the unnaturalness of gardens as controlled and subjugated nature. However, in these works, the unnatural, in the form of materials and digital design methods, is not used to order and control but rather becomes an element that enables the works’ development. I was thinking about how plants grow in a disordered way when activated, through the reiteration of botanical units such as leaves, roots, or branches. My making process is similarly modular—I never have a plan for a work before I start digitally drawing; instead, the works evolve or ‘grow’ through the repetition, manipulation, and subtraction of drawn forms.

ST: The concept of disobedience and refusal is central to your work, particularly in subverting historical taxonomies. Could you explain how you approach this concept through your art?

ASB: In the sculptures, I have reworked botanical illustrations from historical texts like Carl Linnaeus’ Systema Naturae, blending and overlaying them to subvert traditional taxonomy. By merging these markers of difference, I aimed to challenge the idea of classification. I have been influenced by Sara Ahmed's writings on use, particularly her discussion on how the demand to use something properly can be seen as a demand to revere what has been given. I view my misuse of the drawings as an act of disobedience—a refusal to enact a prior history of use.

ST: Art deco elements appear in some of your pieces, symbolizing a move towards independence and a break from colonial influences. What inspired you to integrate this style, and how do you see it interacting with the other themes in your work?

ASB: Deco elements are present in many of the pieces. One of the sculptural works reimagines the frieze of the triumphal arch in Rani Baug in a deco style. This is a colonial monument that remains in the garden today. I was struck by the contrast between the colonial and deco architecture in Mumbai, which has the second-largest collection of art deco buildings in the world. I was interested in how this style could be seen as a statement of independence—a style chosen by Indian architects that was distinctly different from colonial influences.

ST: Your practice often involves translating and reappropriating forms and motifs. How do you approach the process of translation in your work, especially concerning your exploration of diasporic experiences?

ASB: I use translation as a method in my work. I am interested in how something changes through this process—what carries over, what is cut out, and what is necessarily adapted for this transfer. My recent work traces histories of movement, and in this current body of work, it specifically explores the transfer of botanical matter. It is a way of exploring genealogies of dispersion.

ST: Having studied and exhibited in various places worldwide, how have different cultural and historical contexts influenced your artistic journey and the development of your unique style?

ASB: In 2022, I undertook a residency at the British School at Rome, where I researched the city's architecture. Later that year, I was commissioned by Somerset House in London to create work responding to the layered history and architecture of the site. Since then, I have been working in a very site-specific manner, with the location of the exhibitions playing a central role in the development of my work.

ST: As an artist and academic, you straddle the worlds of practice and theory. How does your academic background inform your artistic practice, and how do you navigate the intersection of these two realms?

ASB: I am always interested in the frictions between practice and theory. I believe that the resistances and incompatibilities between the two can be highly generative. Research and writing are core parts of my artistic practice—processes that are also forms of making.

Catch Amba Sayal-Bennett’s "Dispersive Acts" at TARQ, Mumbai, until September 21st, 2024.