Photo Manipulation Before Photoshop: The Art of Darkroom Myths

Long before Photoshop, photographers in the darkroom used clever techniques to alter images—crafting illusions, myths, and political messages that challenged photography’s claim to objectivity and truth from its very beginnings.

In today’s digital age, it is easy to assume that the manipulation of images began with the arrival of Photoshop in the late 1980s. The software has become so synonymous with altering photographs that “to Photoshop” has entered everyday language. Yet the truth is that image manipulation is almost as old as photography itself. Long before pixels and digital layers, photographers in the darkroom were masters of trickery, illusion, and invention.

From the Victorian fascination with spirit photography to political propaganda in the 20th century, the camera has always been a tool not just for documenting reality but for reshaping it. The myths and manipulations of the darkroom reveal that photography has never been the objective witness we often imagine. Instead, it has been a playground of artistry, deception, and experimentation.

The Birth of Photographic Trickery

The invention of photography in the 19th century immediately raised questions about truth and illusion. Early processes such as daguerreotypes and calotypes seemed miraculous: they offered the possibility of capturing reality with mechanical precision. But almost as soon as photographs were made, they were also manipulated.

In the 1850s and 1860s, photographers began experimenting with multiple exposures, combination printing, and hand-painting on negatives to achieve effects that went far beyond simple representation. The darkroom was not merely a place to develop images; it was a workshop of imagination.

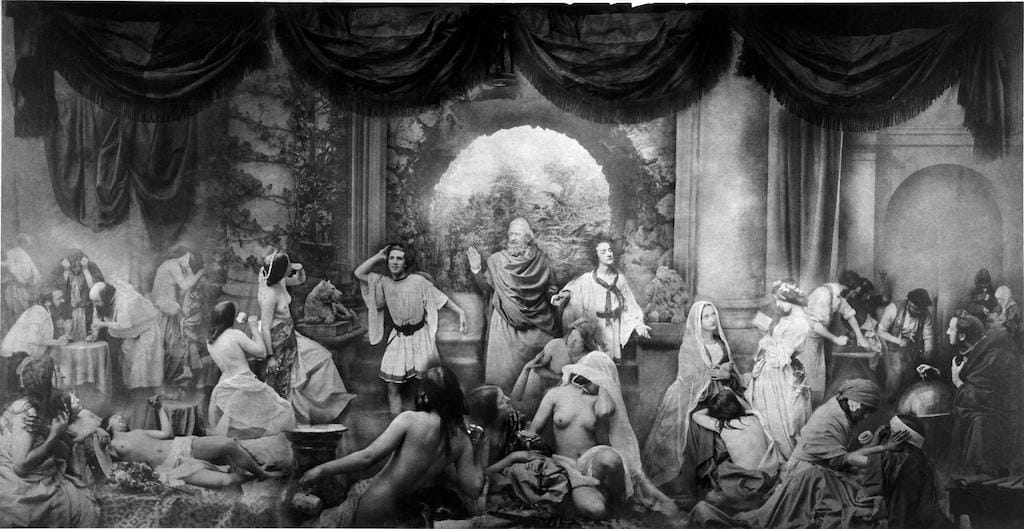

One of the earliest pioneers was Oscar Rejlander, who in 1857 created The Two Ways of Life, a monumental composite photograph made by joining together over thirty separate negatives. The work, which depicts an allegorical scene of vice and virtue, astonished Victorian audiences. For many, it blurred the line between photography and painting, revealing that the camera could construct fiction as easily as it could document fact.

The Victorian Love of Illusion

The Victorians were particularly drawn to photographic trickery. With their fascination for science, mysticism, and the supernatural, they embraced manipulated images as both entertainment and evidence.

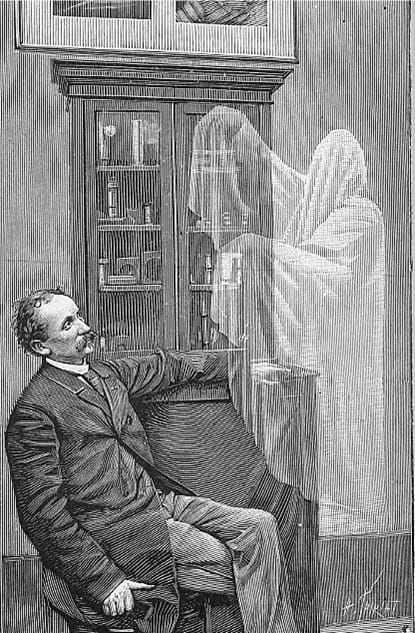

Spirit photography became a craze in the late 19th century, with figures like William H. Mumler claiming to capture ghosts in his portraits. Sitters would pose for a conventional photograph, only to discover spectral shapes and faces hovering behind them once the image was developed. Although many such photographs were later exposed as frauds created through double exposure, they fed into a broader cultural appetite for the mystical.

Other photographers experimented with playful illusions. Double portraits in which the sitter appeared to be shaking hands with themselves, or “decapitated” heads balanced on platters, were created through carefully masked exposures. These images were not necessarily meant to deceive, but rather to amuse — demonstrating both the possibilities of the medium and the creativity of its practitioners.

The Darkroom as a Stage

Techniques of manipulation varied widely, but all required skill, patience, and a deep knowledge of chemistry and optics. Some of the most common methods included:

- Combination printing: Piecing together multiple negatives to form a single, seamless image.

- Double exposure: Exposing the photographic plate twice to create overlapping images.

- Dodging and burning: Selectively lightening or darkening parts of an image during the printing process.

- Retouching: Painting directly on negatives with ink or pencil to alter facial features, smooth imperfections, or erase unwanted objects.

- Photomontage: Cutting and pasting prints together, then rephotographing them to create a unified composition.

The darkroom became a theatre of possibility, where the manipulation of light and shadow could produce results as dramatic as any stage illusion. In this sense, photographers were not simply recorders of reality but conjurers of myths.

Manipulation in the Service of Power

While many manipulations were playful or artistic, others carried heavy political weight. In the 20th century, photographic retouching became a tool of propaganda.

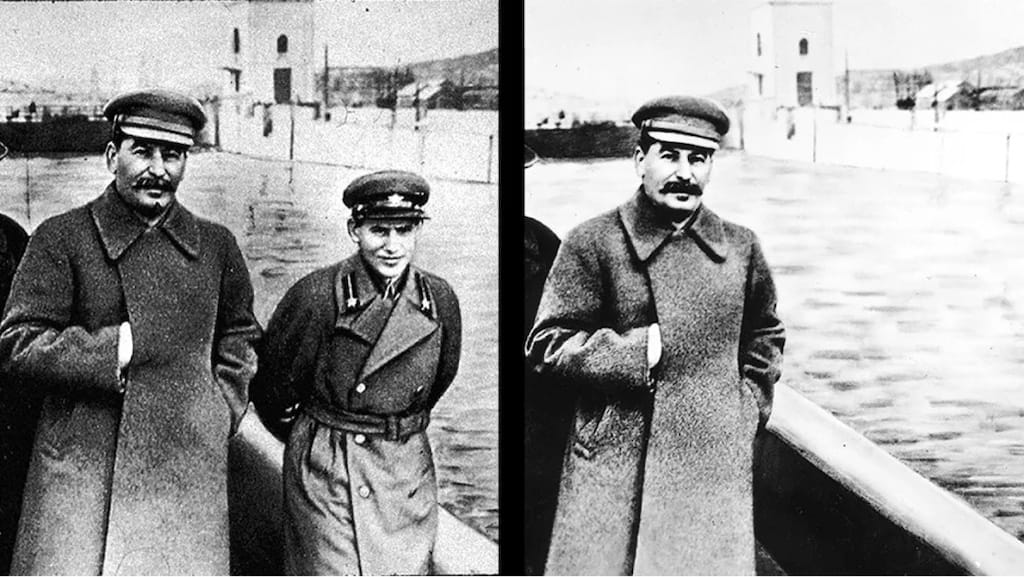

Perhaps the most infamous examples come from Stalinist Russia. Photographs of party officials were routinely altered to remove individuals who had fallen out of favour — quite literally erasing them from history. Entire figures were painted out of negatives, leaving only those loyal to the regime. These images were then circulated as “truth,” shaping public memory through deliberate manipulation.

Elsewhere, newspapers and magazines employed retouching to construct idealised narratives. Press photographs were adjusted to flatter public figures, erase flaws, or create scenes that never quite occurred. This was not always malicious; sometimes it was merely aesthetic. Yet it reinforced the myth of photography as objective reality, even as it was being reshaped in the darkroom.

Artistic Uses of Manipulation

Alongside propaganda, photographers used manipulation as a legitimate artistic strategy. The Surrealists, in particular, embraced photomontage and darkroom techniques to explore the unconscious. Artists such as Man Ray and Hannah Höch combined fragments of images to create dreamlike or unsettling compositions, questioning the boundaries of reality.

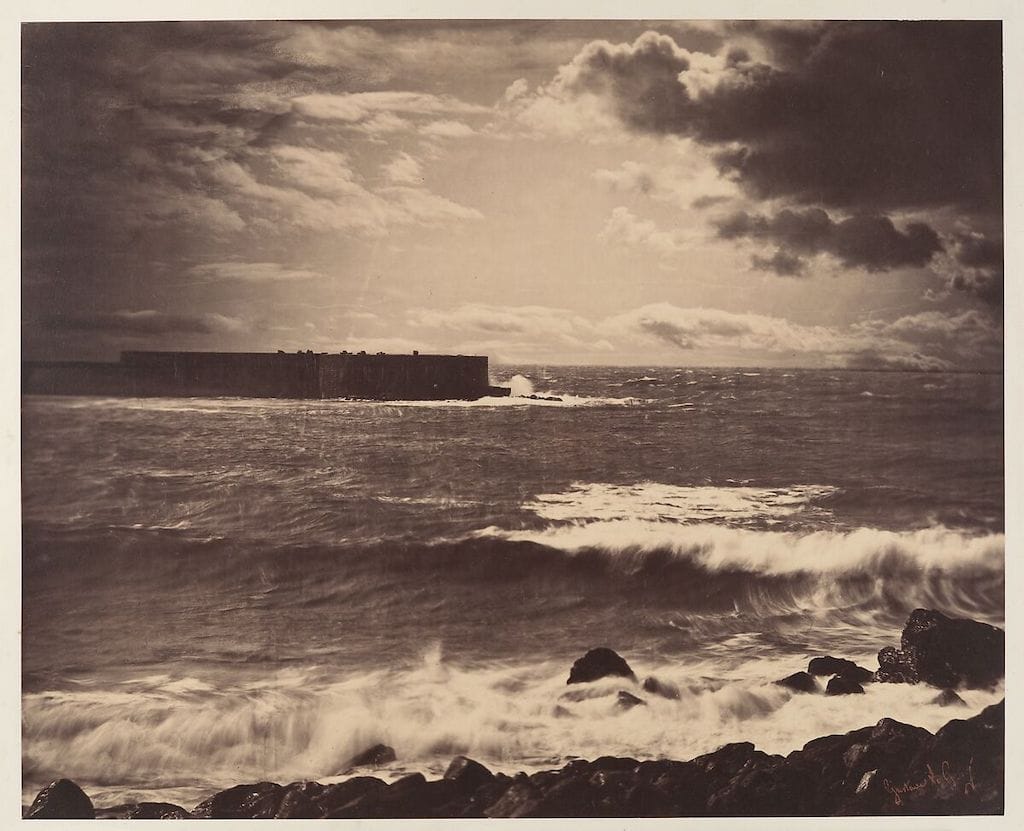

French photographer Gustave Le Gray astonished 19th-century audiences with his seascapes, which combined separate negatives for sea and sky to overcome the technical limitations of early photographic emulsions. By printing two exposures onto a single sheet—often made at different times or places—he achieved balanced compositions with dramatic skies and reflective waters. More than a technical triumph, Le Gray’s work introduced a poetic sensibility to photography that was unprecedented at the time.

Photographic manipulation also allowed for the creation of impossible landscapes and scenes. Gustave Le Gray, for example, produced seascapes in the 1850s by combining one negative of the sky with another of the sea, since early photographic processes could not capture both exposures correctly in a single shot. His images were celebrated not as deceit but as artistry — a means of overcoming technical limitations with creative ingenuity.

These works remind us that manipulation was not inherently deceptive; it was also a form of expression, much like a painter choosing which details to emphasise or omit.

The Myth of Photographic Truth

Underlying the history of darkroom manipulation is a broader myth: that photography is a mirror of reality. From its inception, photography carried an aura of truth because it seemed to be produced by a machine, free from human interpretation. Yet the hand of the photographer was always present — in the framing, the exposure, and the darkroom decisions that followed.

The long history of manipulation reveals that photography has never been a neutral medium. Whether through retouching a portrait, staging a scene, or erasing an unwanted figure, photographers shaped images to tell particular stories. In this sense, Photoshop did not invent manipulation; it simply made visible, and accessible, what had long been possible in the darkroom.

Echoes in the Digital Age

Today, debates about “fake news,” deepfakes, and digital editing echo these earlier anxieties. Just as Victorians wrestled with spirit photographs, we grapple with AI-generated images that blur fact and fiction. The tools have changed, but the underlying questions remain the same: Can photography be trusted? Where does artistry end and deception begin?

Ironically, awareness of Photoshop has made viewers more sceptical of images, while in the 19th and early 20th centuries manipulated photographs were often taken at face value. This shift suggests that photography’s authority as a truthful medium has always been fragile, easily undermined once its tricks are revealed.

Lessons from the Darkroom

Exploring the myths of darkroom manipulation teaches us several important lessons:

- Photography is never neutral. Every photograph reflects choices, whether in framing, exposure, or manipulation.

- Manipulation is not new. Digital tools have accelerated the process, but the impulse to alter images is as old as photography itself.

- Context matters. Manipulation used for art or humour differs greatly from that used for propaganda or deception.

- Scepticism is healthy. Just as Victorians were fooled by spirit photographs, we must approach modern images with critical awareness.

Conclusion

The history of photographic manipulation before Photoshop reminds us that the camera has always been both witness and trickster. The darkroom was a place of myths, where chemical magic could conjure ghosts, erase enemies, or create impossible skies. Rather than diminishing photography, these manipulations reveal its richness as a medium. They remind us that images are not simply reflections of the world but interpretations of it — shaped by human imagination, power, and desire.