Masters at Odds: The Da Vinci–Michelangelo Rivalry

In Renaissance Italy’s crucible of creativity, Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo clashed in a battle of artistic philosophies—science versus spirituality, observation versus abstraction—each driven by ambition and genius to redefine the boundaries of Western art.

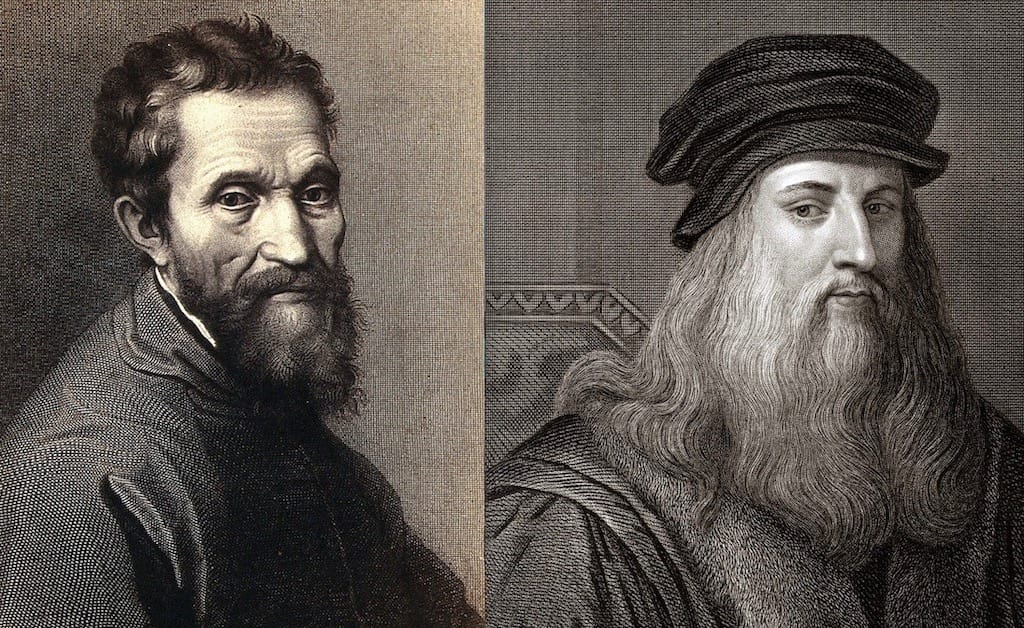

The turn of the sixteenth century in Italy was nothing short of a golden age for art. Florence and Rome pulsed with creative energy, each city vying to outshine the other in artistic splendour. In this vibrant milieu emerged two towering figures whose names have become synonymous with genius: Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) and Michelangelo Buonarroti (1475–1564). Though both artists shared a voracious appetite for innovation and a relentless pursuit of excellence, their personalities, philosophies and working methods stood in stark contrast, giving rise to one of the most storied rivalries in art history. This article explores the origins, nature and enduring legacy of the artistic rivalry between Leonardo and Michelangelo.

Florence: The Cradle of Competition

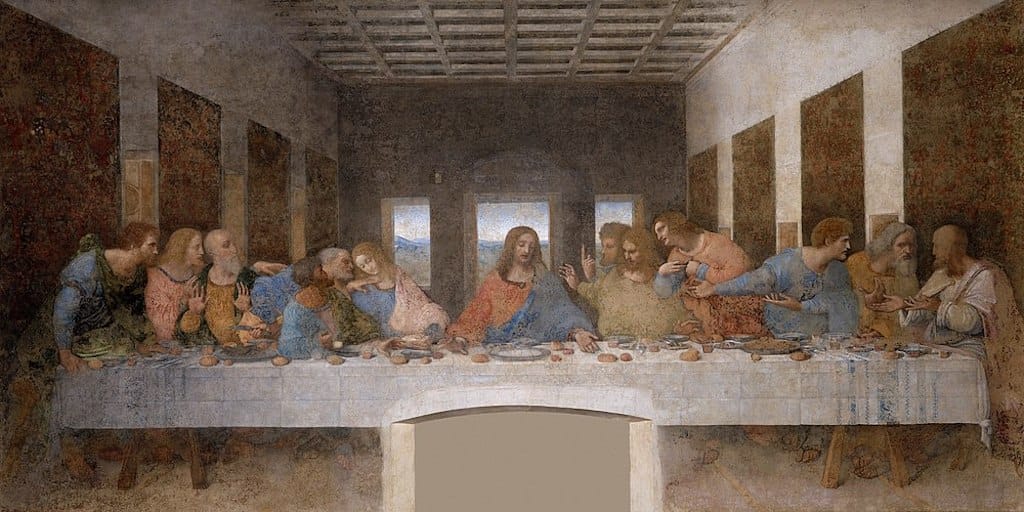

By the late 1480s, Leonardo da Vinci had already established himself as a formidable talent in Florence. His mastery of sfumato—an approach to shading that produces soft transitions between tones—lent his figures an unparalleled sense of realism and subtlety. Works such as The Baptism of Christ (c. 1472–75), executed alongside his master Andrea del Verrocchio, showcased a dawning virtuosity that would blossom in later masterpieces like The Last Supper.

Meanwhile, Michelangelo arrived in Florence as a precocious teenager under the patronage of Lorenzo de’ Medici. Though his early works were rooted in sculpture rather than painting, Michelangelo’s marble carvings, such as the Sleeping Ariadne (c. 1490), hinted at a power and dynamism that would come to define his style. By the time he created the marble David (1501–04), the young sculptor had captured the city’s imagination, signalling that an artistic titan had arrived.

The Source of Rivalry: Divergent Approaches

Leonardo and Michelangelo were united in their quest to depict the human figure with unprecedented fidelity, yet their methods and temperaments differed radically. Leonardo, ever the polymath, approached art through the lens of scientific inquiry. His meticulous anatomical studies—sketches borne of dissections of human cadavers—sought to decipher the underlying structures that animated flesh and bone. His notebooks, filled with observations on light, optics and botany, reveal a mind constantly probing the natural world.

Michelangelo, by contrast, regarded the stone as a living entity awaiting liberation by the sculptor’s chisel. His concept of “capturing the soul” within marble infused his works with an almost metaphysical intensity. While Leonardo sought an illustrative realism grounded in empirical observation, Michelangelo harnessed the emotive power of the form, exaggerating musculature and gesture to evoke drama.

These competing philosophies reached a symbolic crescendo in 1504, when both artists were commissioned to produce monumental public works in Florence. Leonardo was asked to paint a battle scene, known as The Battle of Anghiari, on the east wall of the Sala del Gran Consiglio in the Palazzo Vecchio. Michelangelo, almost simultaneously, received a commission to paint the Battle of Cascina on the opposite wall.

The Battle of Anghiari versus the Battle of Cascina

Leonardo’s Battle of Anghiari, though never completed, became legendary through preparatory drawings and the copies made by his pupil Peter Paul Rubens. The embattled horses, straining figures and swirling conflict demonstrated an unparalleled mastery of movement. Yet, Leonardo’s experimental use of an oil-and-tempera mixture to expedite drying led to the work’s premature deterioration.

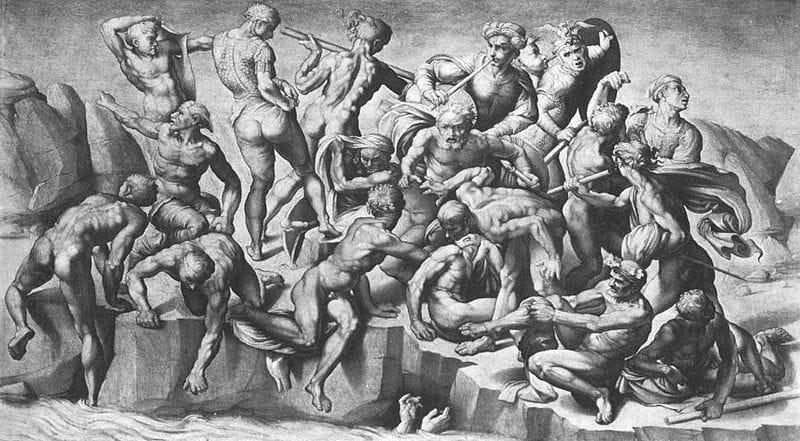

Michelangelo’s Battle of Cascina remained no less mythic. Though never painted either—he left Florence for Rome before completing the commission—Michelangelo’s cartoon depicts Florentine militiamen surprised at their bath in the Arno. The cartoon survives in copies, its muscular forms and dramatic poses prefiguring the Sistine ceiling’s Titans. His figures, arrested mid-motion, exude tension and restrained power.

Though both murals perished, the very act of direct comparison cemented the narrative of rivalry. Florence watched, rapt, as each master strove to outdo the other not merely in technical skill but in expressive force.

Clash in Rome: From Florence to the Vatican

The schism between Leonardo and Michelangelo widened further with their travels to Rome. Leonardo arrived circa 1513 under the patronage of Giuliano de' Medici and was appointed court painter to Pope Leo X. His last great project, the unfulfilled Saint Anne cartoon, again demonstrates his penchant for complex, multi-figure compositions and ethereal atmospherics.

Michelangelo meanwhile was summoned to Rome in 1505 to sculpt the tomb of Pope Julius II. When political and financial setbacks stalled the project, Michelangelo transitioned to painting, embarking on the Sistine Chapel ceiling in 1508. Over four grueling years, he completed an opus of biblical grandeur: from the Creation of Adam to the Last Judgment, each fresco affirmed his belief that art could unite the celestial with the corporeal.

Leonardo’s response to Michelangelo’s frescoes remains a matter of conjecture; however, his later works, such as the enigmatic Mona Lisa and the unfinisheld Adoration of the Magi, suggest a withdrawal from public competition towards more introspective pursuits. Michelangelo, conversely, thrived on public acclaim and controversy alike.

Personality and Polemic

Contemporary accounts depict Leonardo as urbane, curious and affable, though prone to procrastination. Giorgio Vasari’s Lives describes Leonardo as a jovial guest at scholarly gatherings, his wit and theatrical demonstrations of anatomical dissections delighting audiences.

Michelangelo, by contrast, emerges as fierce and solitary, consumed by his work. He eschewed society and often quarrelled with patrons over payments and artistic control. Anecdotes recount Michelangelo’s scornful jibe at Leonardo: “He paints men like gods, but they look like puppets.” Leonardo, in turn, is said to have dismissed Michelangelo’s figures as “unfinished chalk sketches.” While these barbings may be apocryphal, they capture the competitive spirit that animated their relationship.

Legacy of Rivalry

The artistic rivalry between Leonardo and Michelangelo bequeathed a lasting legacy to Western art. Their divergent methodologies expanded the boundaries of artistic expression, one through observation and the other through sublime abstraction of form. The story of their rivalry underscores the Renaissance tension between science and spirituality, reason and inspiration.

In subsequent centuries, artists and scholars would look to both masters as twin pillars. Leonardo’s notebooks inspired anatomists and inventors; Michelangelo’s frescoes influenced sculptors and painters seeking expressive drama. Exhibitions, monographs and films have revisited their rivalry, ensuring that the narrative remains as compelling today as it was in the courts and workshops of Renaissance Italy.

Conclusion

The competition between Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo transcended mere rivalry; it represented a dialectic of creative philosophies. In their contrasting visions—one grounded in scientific empiricism, the other in metaphysical aspiration—they captured the dual essence of the Renaissance itself. Though they never shared a single studio or collaborated on a project, the interplay of their ambitions enriched the art world and shaped the trajectory of Western aesthetics for centuries to come.