Manu Parekh’s 'Flower Sutra': A Journey of Faith, Energy, and Artistic Expression

In 'Flower Sutra', Manu Parekh continues his lifelong exploration of dualities—order and chaos, creation and decay—through vivid, pulsating compositions. In this interview, he reflects on faith, movement, and the timeless presence of flowers in his art.

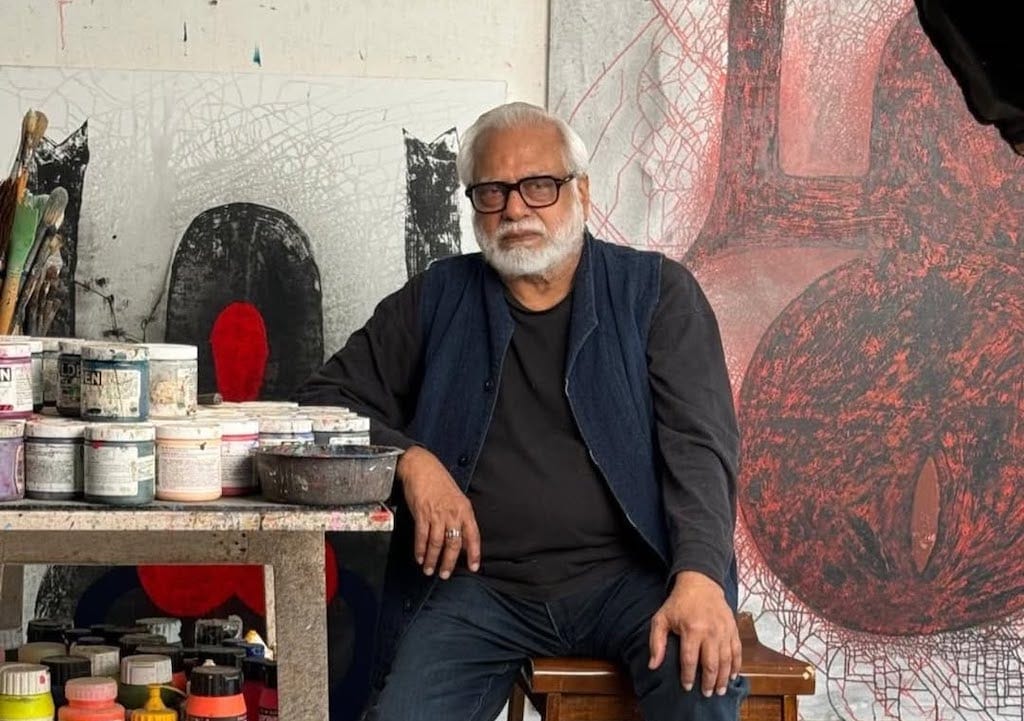

For over five decades, Manu Parekh has been a commanding presence in Indian contemporary art, his canvases brimming with energy, contrast, and an exploration of life’s fundamental dualities. At 86, he remains as vibrant and prolific as ever, channeling his lifelong fascination with movement, faith, and the natural world into his latest exhibition, Flower Sutra, on view at Nature Morte, New Delhi.

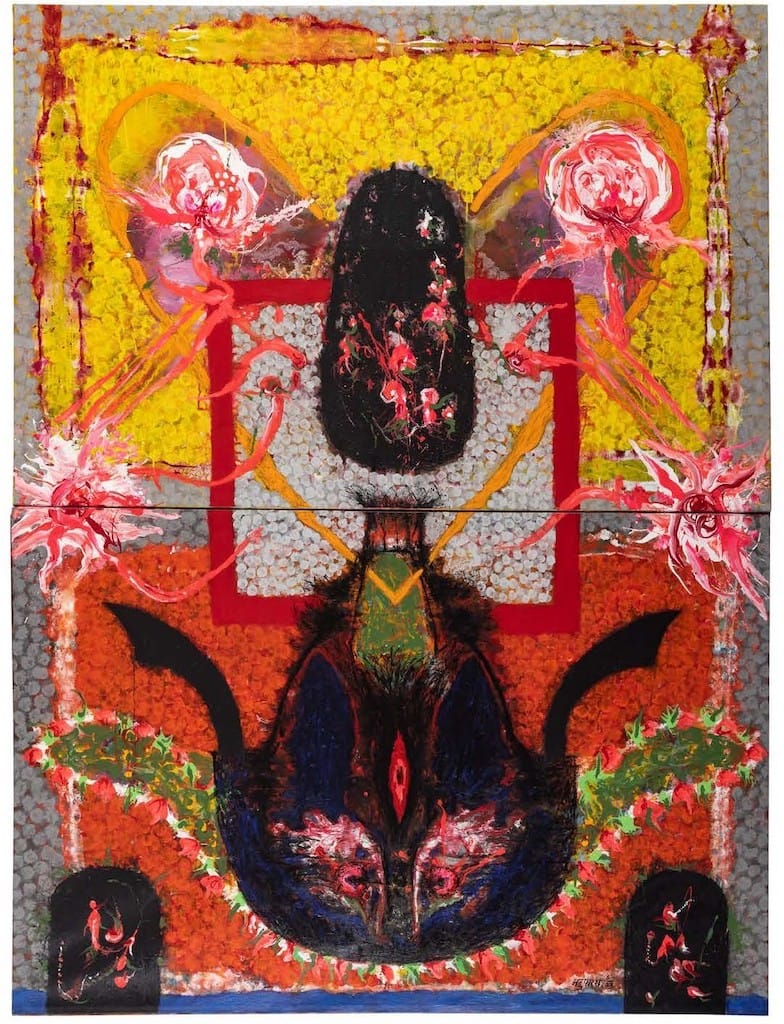

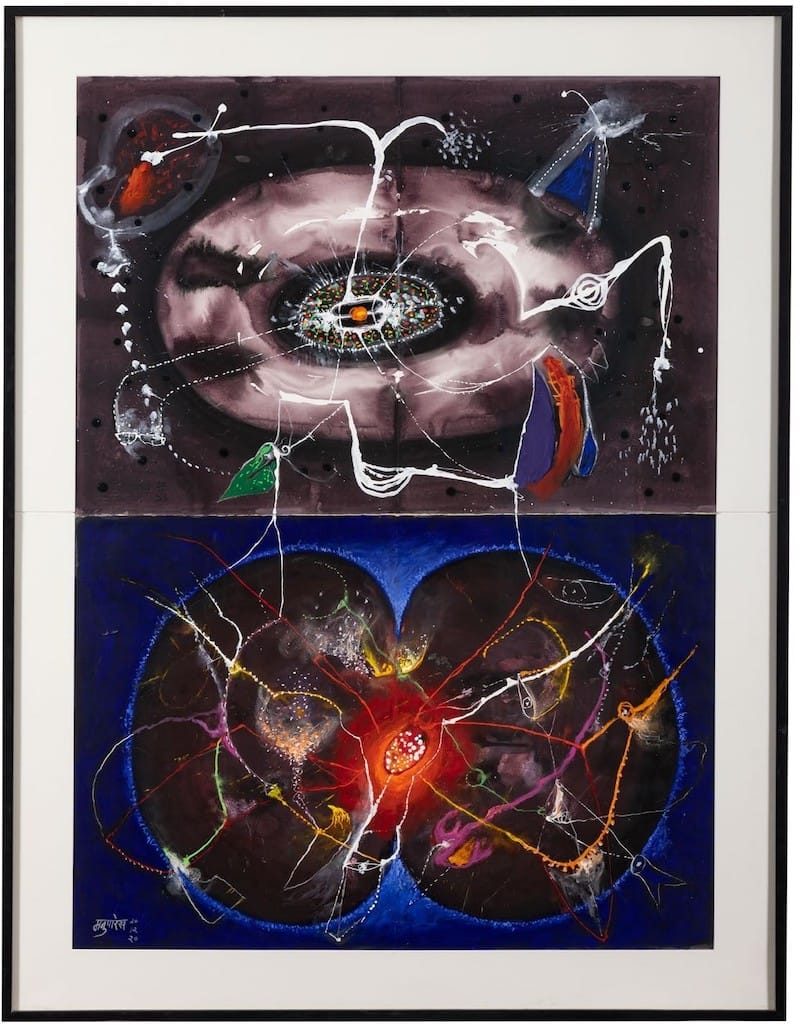

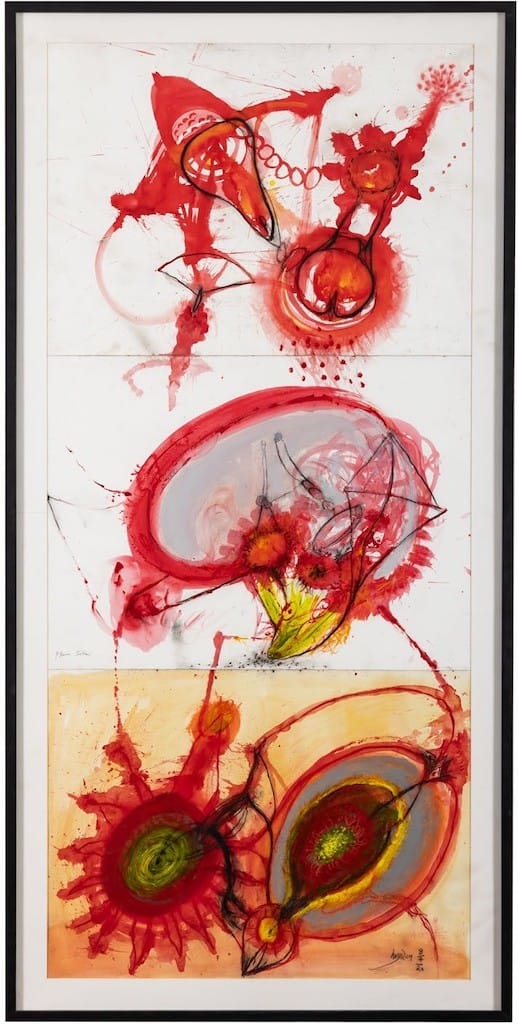

Parekh’s paintings have always been alive with tensions—between order and chaos, stillness and movement, creation and decay. His latest body of work continues this dynamic approach, embracing flux rather than seeking to control it. Thick impasto collides with delicate washes, jagged lines cut through fluid colour, and every stroke hums with spontaneity and intention. Flowers, a recurring motif in his practice, serve as both subject and metaphor, embodying transience, devotion, and the cycles of life. As Parekh observes, "Where there is faith, there will be the presence of flowers. Life, birth, marriage, and death: flowers will be there."

Parekh’s artistic journey has been shaped by diverse influences, from his early exposure to vernacular traditions such as rangoli and embroidery to his time in Kolkata, where the raw energy of the city deeply informed his visual language. Though he initially struggled to find inspiration after moving to Delhi in 1975, it was in Varanasi that his creativity was reignited, leading to the expressive, deeply spiritual works for which he is renowned today.

In this interview, Parekh delves into the ideas behind Flower Sutra, his process of creating movement on canvas, and the enduring role of faith and nature in his art.

Nikhil Sardana: Your new exhibition, Flower Sutra, explores the recurring motif of flowers. What drew you to this theme, and how does it relate to the dualities you often explore in your work?

Manu Parekh: The idea first came to me through painting. The flower vase is an important and popular subject—both in Western painting traditions and in India. I was particularly struck by Rabindranath Tagore’s depictions of flowers. His flowers were expressive and different; they often resembled powerful faces.

Later, my visits to Varanasi deepened this fascination. I realised that, much like human existence, flowers have their own destiny. One day, they may adorn a deity’s head; another day, they may rest on a funeral pyre. Their journey changes the moment they are plucked. This transience—this inevitable transformation—echoes the human condition. It is this realisation that continues to inform my work.

NS: Your practice has always embraced the tension between order and chaos, movement and stillness. How do these opposing forces manifest in your latest work?

MP: This interplay is not new—it has been present in my work for years. It first became clear to me when I moved to Kolkata in 1965. At that time, I was 24 or 25 years old, and Kolkata was a city of stark contrasts. It was chaotic yet structured, disorderly yet disciplined.

That duality was fascinating to me, and I realised that life itself operates in a similar way. People find ways to exist within contradictions. In my work, this tension manifests through geometry and chaos, structure and spontaneity. This continuity has remained with me since my early days in Kolkata.

NS: Energy plays a significant role in your paintings, with your brushstrokes capturing movement and spontaneity. Can you talk about your approach to layering and mark-making in this body of work?

MP: I have always been drawn to expressionism. My brushstrokes are instinctive, spontaneous. Even in my early work, this expressiveness was present, and it remains today. I have long admired the Blue Rider group and German expressionists, and in India, I have always been drawn to Tagore and Souza. Their ability to channel raw emotion through form and colour resonates deeply with me.

India itself is a crowded, dynamic country, full of energy and movement. My paintings reflect this intensity. There is no concept of empty space in my work because, for me, emptiness does not exist in India. The expressive brushstrokes, the layering of paint, the dynamic compositions—all of these elements are a response to my surroundings.

NS: Do you plan your paintings in advance?

MP: Never. I don’t plan compositions or colours in a rigid way. However, I do a lot of drawing. The habit of constantly moving my hand, sketching forms, playing with tones and colours—that preparation is always present. It helps me. It allows me to respond instinctively when I begin painting.

NS: Do you often change things as you work?

MP: Yes, a lot. That’s why layering plays such a crucial role in my work. There are multiple layers of paint, strokes upon strokes, lines over lines. The painting evolves organically. I leave many works unfinished, sometimes for days, even months. When I return to them, I see them with fresh eyes.

NS: You have spoken about faith and flowers as constants across cultures. How do you see these ideas evolving in your art, particularly in the context of contemporary India?

MP: Faith and ritual are deeply embedded in Indian life. Flowers play a role in almost every tradition, every ceremony. My time in Kolkata and Varanasi reinforced my awareness of this.

I arrived in Kolkata in 1965 and lived there for a decade, until 1975. It was an incredibly vibrant time—theatre, cinema, literature, and art were thriving. Within six months, I became a member of the Society of Contemporary Artists, alongside figures like Shyamal Dutta Ray, Ganesh Pyne, and Vikas Bhattacharya. I was also welcomed into the Bengali intellectual community. Learning the language allowed me to truly immerse myself in their culture.

At the same time, I was influenced by global counterculture movements. I remember hearing A Hard Day’s Night by The Beatles and being struck by the line: We’ve been working like a dog. That energy—of struggle, of rebellion—was something I found in Kolkata as well. The poet Allen Ginsberg had spent time in the city in the 1960s, engaging with the Hungry Generation poets like Shakti Chattopadhyay and Sunil Gangopadhyay. Their engagement with Indian spirituality, their embrace of asceticism—living on just a dollar a day—was something that fascinated me. This intersection of cultures, of ideas, has always been important to my work.

NS: Has your relationship with Kolkata and Varanasi changed over the years? Do you still visit?

MP: Not as often. But their influence remains. Kolkata, in particular, is a city of contradictions—politically charged yet deeply spiritual. Figures like Ramakrishna Paramahamsa, Prabhupada, and Maharishi Mahesh Yogi have had a lasting impact on me. During Durga Puja, the entire city transforms. Unlike many other parts of India, where male deities dominate, Kolkata is devoted to the worship of Durga and Kali. That spirit, that energy, has always stayed with me.

When I moved to Delhi, I found myself missing Kolkata terribly. My world felt dry in comparison. After struggling for a few years, I knew I needed to find a place that could fill that void. That’s when I began travelling to Varanasi.

NS: As a painter whose career spans decades, what excites you about making art today?

MP: The same things that always have—colour, tone, line, texture. These fundamental elements remain endlessly exciting to me. They are my tools, and they allow me to shape my ideas, my experiences. I still feel as though I could paint for another 20 years.

NS: Your work has often drawn from vernacular traditions, textiles, and crafts. How do these elements continue to inform your contemporary practice?

MP: I have immense respect for craftsmanship. India has a rich heritage of handicrafts, handloom textiles, and traditional techniques. I worked closely with Pupul Jayakar for 25 years, which gave me an unparalleled exposure to India’s diverse craft traditions.

Textiles, in particular, are deeply connected to our cultural identity. India’s unstitched garments—the saree and dhoti—are remarkable. Despite being simple lengths of fabric, they are worn in countless ways across different regions. They carry history, symbolism, and a sense of occasion. This connection between textiles and rituals, between fabric and life, continues to inspire me.

NS: Having been an integral part of Indian modernism, what are your thoughts on the younger generation of artists? Do you see any parallels between your early years and their current challenges?

MP: Our time was very difficult. There were few opportunities, and many of my peers turned to teaching or design work to survive. Today, there are far more possibilities, largely due to the art market. But that comes with its own challenges.

Now, commercial success is attainable, but creative success is another matter entirely. One must be careful not to lose sight of artistic integrity. Art is not a fleeting trend—it must have depth, substance, and timelessness.

In every era, artists must navigate their own paths. But whether then or now, one thing remains unchanged: the need for clarity, honesty, and a strong personal vision. Those who stay true to their artistic morality will always create meaningful work.

Manu Parekh’s exhibition, Flower Sutra, is on view at Nature Morte, New Delhi, until Sunday, March 30th, 2025.