Lojithan Ram at PRSFG Colombo: Echoes of Memory and Resilience

Drawing on Sri Lankan Tamil heritage, Lojithan Ram’s debut exhibition weaves memory, ritual, and resilience into cyanotypes and sculptures—offering a poetic meditation on loss, cultural continuity, and the quiet endurance of belonging.

Lojithan Ram’s debut solo exhibition, Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum, offers an eloquent meditation on memory, loss and the fragile tenacity of cultural roots. Drawing on his Sri Lankan Tamil heritage and formative years in Batticaloa, Ram weaves personal narratives and communal histories into a poetic visual language. Over the course of more than two dozen works—spanning cyanotype prints and sculptural installations—he asks viewers to consider how meaning and belonging persist, even as the circumstances that gave rise to them slip away.

At the heart of Ram’s exhibition lies its title, borrowed from an ancient verse by the Tamil poetess Avvaiyar. In her poem, she describes a sun‑dried pond once favoured by birds and aquatic plants; when the water disappears, the birds flee, but the koṭṭi, āmpal and neythal remain, their roots intertwined with cracked earth. This image resonated with Ram as a metaphor for emotional endurance. He reflects that “like the birds, we move from place to place, seeking survival, safety or new beginnings. But our memories stay rooted… Now, all I carry are memories. This exhibition emerges from those emotional sediments as an archive of what remains when everything else has moved on.”

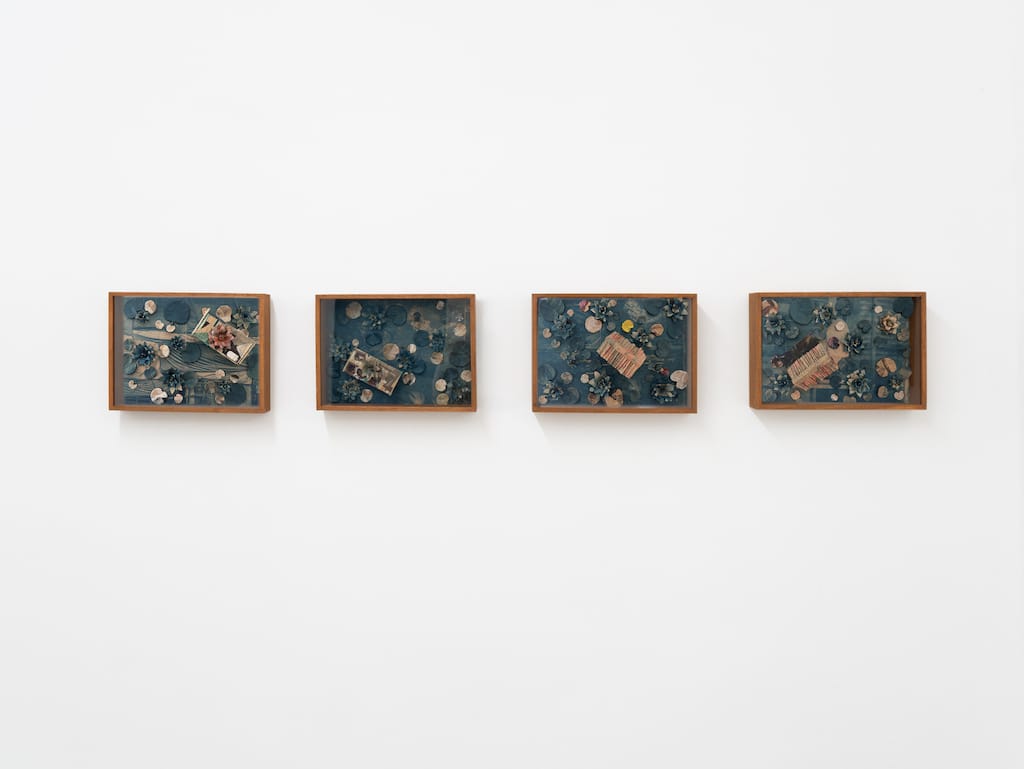

Installation view of Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum

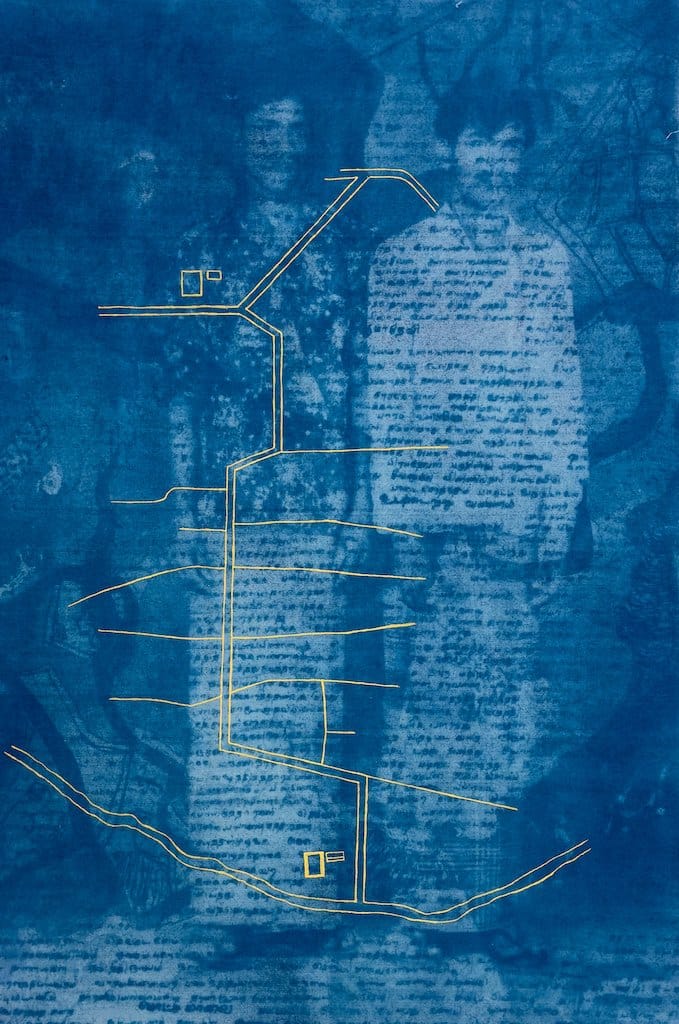

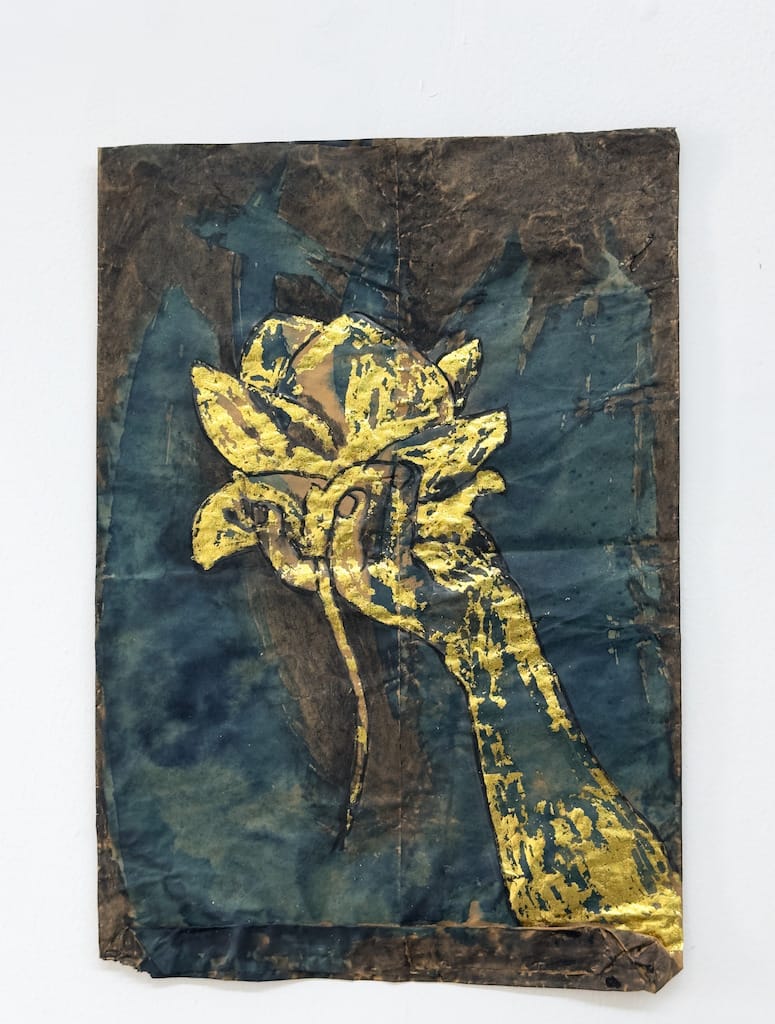

Ram’s primary medium, the cyanotype, reinforces this sense of layered remembrance. His large‑scale blue prints merge archival family photographs with verses from the Vaikuntha Ammanai—a thirty‑one‑day mourning chant practised in Tamil‑speaking communities—and botanical motifs. In describing these works, he emphasises their dual nature: “My cyanotypes are emotional sanctuaries built from memory, language and inherited stories,” he explains, noting that the ancient hymns and ritual chants he heard at home were “constant threads in our household, where my mother practised as a traditional poetess.” By pressing these elements into the photosensitive chemistry of cyanotype, Ram transforms his grief and longing into a tangible offering: “They act as prayers, as offerings, as maps to a past that still shapes the present.”

This alchemy of loss and beauty finds its tone in the resonant shade of blue. For Ram, the hue is never merely aesthetic; it carries “a profound nostalgia—it is the colour of water, memory, sky and longing.” Sourcing cyanotype chemicals in Sri Lanka proved challenging, so he built a makeshift darkroom and taught himself the process through online tutorials and countless experiments. The resulting prints bear the marks of this labour—irregular edges, delicate bleeds and subtle variations in tone—reminding viewers that memory, like pigment, can never be totally controlled or contained.

Ram’s upbringing in Batticaloa, a region whose complex history of conflict and displacement is often overshadowed by narratives focused on northern Sri Lanka, profoundly informs his perspective. He recalls that “my uncle and cousin disappeared during the conflict, and others in my family were affected by political violence between the 1980s and 2000s. What we have now are fragments—faded black‑and‑white photographs, half‑told stories and memories carried in the voices of our elders.” This vacuum of official record spurred him to found the Batticaloa Photo‑History Archive in 2021, a grassroots project that gathers vernacular images from personal collections and old photo studios. What began as a personal endeavour has become an ongoing collaborative endeavour—an act of communal witnessing that underpins much of his practice.

In works such as Poigai, Ram extends this impulse towards ethical remembrance into three dimensions. Inspired by drawings on repurposed brown paper bags he made in 2018, the sculptural objects conjure an imagined lotus pond where everyday items—bicycles, stacks of paper, domestic pottery—float among oversized blooms. These familiar objects, he says, become “vessels that hold personal significance,” with a bicycle’s paper load paying homage to his father’s life and labour. Far from literal re‑creations, the Poigai sculptures serve as “emotional cartographies,” sculpted from the textures and forms of memory rather than concrete topography. In this way, they embody both the desire for rootedness and the impossibility of returning to an original moment.

Another central thread in the exhibition is the integration of the Vaikuntha Ammanai lament into visual form. Historically recited in family homes for a month after a death, the chant draws on epics like the Mahabharata to offer solace and instruction. Ram insists that these hymns are “not just about loss; they are also about resilience, preparing the living to move forward by carrying the dead in memory and prayer.” By inscribing lines of the chant onto cyanotype surfaces—sometimes so faint they blur with botanical patterns—he captures the fine boundary between mourning and celebration, absence and presence.

While this solo exhibition is very much Ram’s personal statement, it is also shaped by his long‑standing commitment to collaborative, community‑led art. As co‑founder of We Are From Here, a collective project documenting lives in Colombo’s Slave Island neighbourhood, he learned that “collaboration is not always about working side by side; it is about acknowledging that our stories are entangled, and that my practice would not exist without the contributions of others.” Even when he works alone in his studio, the voices of neighbours, elders and fellow artists resonate through his work, reminding viewers that individual history is inseparable from collective memory.

This interplay between personal and communal extends to Ram’s reflection on the nature of displacement itself. Art, he believes, offers not only a means of making peace with loss but also of perpetually questioning it. “Displacement is not just a historical condition; it is an ongoing process encountered by many in the modern world,” he observes. By linking his own narrative to mythological stories and shared traumas, he endeavours to create a space in which others might “see parts of themselves.” In this sense, the exhibition becomes less a finished thesis than a pause for reflection—a place “to witness and to hold space for all that has been lost and all that still endures.”

Visually, Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum is as much an exercise in restraint as it is in elaboration. Many of the cyanotypes are presented with wide margins of unexposed paper, emphasising their neutrality and inviting quiet contemplation. Sculptural elements are encountered at varying heights—some gathered in a large floor installation that invites viewers to peer down into its layered details, while others are mounted on the wall in a way that reveals their three-dimensional qualities from multiple angles. This understated presentation augments rather than distracts from the underlying narratives of loss and resilience.

Installation view of Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum

Perhaps the most striking aspect of Ram’s debut is the confidence with which he occupies his new role as a visual artist across media. Though trained in painting at the Ramanathan Academy of Fine Arts, University of Jaffna, he spent many years known primarily as a documentary photographer. Stepping beyond the boundaries of the photographic frame, he has embraced the unpredictability of analogue processes and the conceptual breadth of sculpture. Looking back on the eighteen months required to realise these works, he notes, “It took time, experimentation and failure to arrive at a place of clarity. But through this process, I fell in love with the practice.”

Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum is an act of bearing witness—both to individual pathways of grief and to the collective resilience of a community that has endured erasure. Ram does not offer tidy resolutions; instead, he situates viewers in a netherworld between remembrance and forgetting, absence and presence. It is in this liminal realm—where roots remain even as water ebbs—that his work finds its deepest resonance. Here, the precise hue of blue, the delicate imprint of lost photographs and the whispered lines of ancient hymns gather to form a testament: that memory, however fragile, can outlast the forces that seek to wash it away.

Arra Kuļamum, Kottiyum, Āmpalum is on view through 23 June at Paradise Road Saskia Fernando Gallery, 41 Horton Place, Colombo 07, Sri Lanka.