Las Meninas: Velázquez’s Mystery of Gaze and Power

Velázquez’s 'Las Meninas' transforms a royal portrait into a profound meditation on gaze, power and perception, inviting viewers into a shifting world where artist, subject and spectator continuously redefine the act of seeing.

Few paintings in Western art history have provoked as much fascination, debate, and scholarship as Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas. Completed in 1656 during the height of the Spanish Golden Age, the painting has long been celebrated not simply as a technical masterpiece but as a philosophical puzzle. Its intricate choreography of glances, spatial ambiguities, and subtle assertions of hierarchy transforms what might have been a straightforward court portrait into a labyrinth of meanings. More than three centuries later, Las Meninas continues to invite questions rather than offer answers, challenging every viewer to reconsider how art can construct, manipulate, and even destabilize the very notion of seeing.

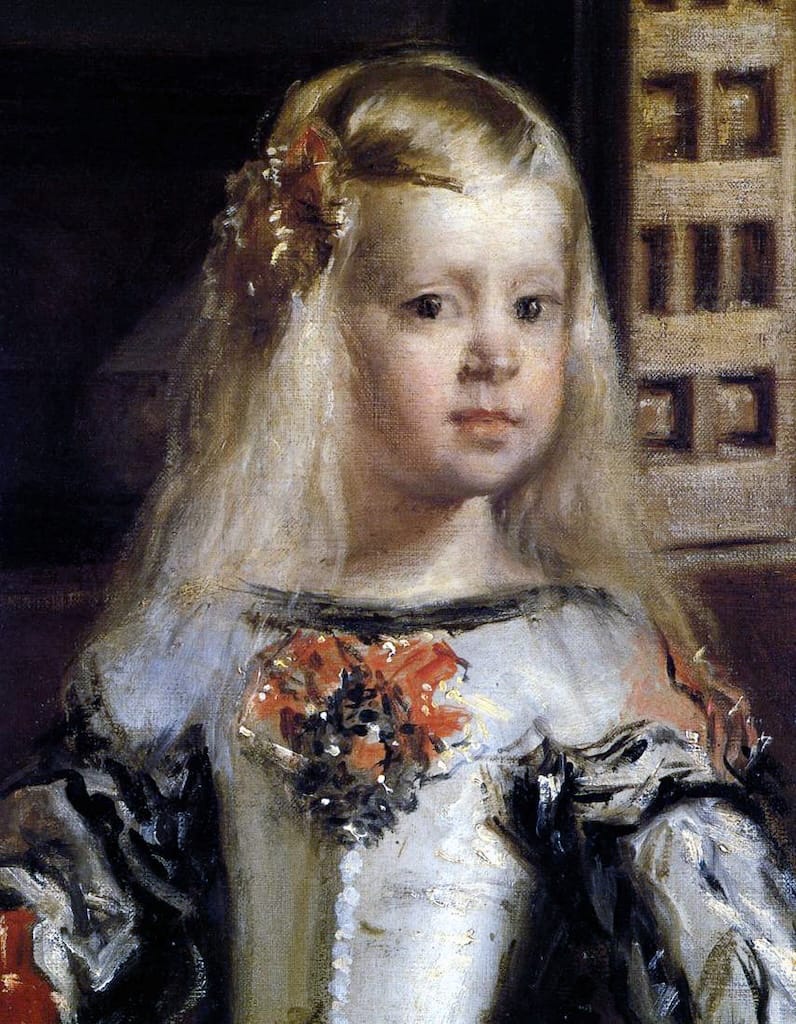

At the center of the canvas stands the young Infanta Margarita, daughter of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana of Austria. She is brightly illuminated, her blonde hair and ornate cream-coloured dress catching the light that pours in from a window on the right. Around her, attendants hover in a bustling but controlled scene. Yet, for all the ostensible focus on the princess, the painting refuses to behave like a typical royal portrait. Velázquez himself stands prominently at the left, brush in hand, paused mid stroke. His eyes meet the viewer with startling directness. The presence of the artist inside the scene, openly acknowledging his own act of creation, suggests something far larger at work. Instead of displaying royal magnificence alone, Las Meninas places the act of painting and the politics of looking at the very center of power.

The Problem of the Viewer

One of the most intriguing aspects of Las Meninas is the way Velázquez manipulates the position of the viewer. The painting seems to draw the spectator into the room, as though stepping across a threshold into the artist’s studio within the Alcázar palace. Velázquez’s gaze fixes on us with a quiet intensity, as if measuring the distance between painter and observer, between creation and reception. But who exactly is being looked at? And who is looking back?

The mirror at the rear of the room provides the most tantalizing clue. It reflects the faint, ghostlike images of King Philip IV and Queen Mariana, positioned exactly where the viewer would stand outside the frame. This subtle device implies that the royal couple occupies the spectator’s space. Velázquez, then, is not looking at us but at the king and queen. The Infanta and her attendants are also turned toward this unseen pair. The painting becomes a scene in which the sovereigns are both present and absent, visible only as reflections yet dominating the gaze of every figure.

This strategy achieves something astonishing. Velázquez transforms the audience into the monarchs themselves. Standing before Las Meninas, we are placed in a position of power yet also of insecurity, for the painting reveals how perception can be both empowering and manipulated. The viewer’s role becomes central to the work’s meaning. Vision is never neutral; it is a field in which authority is negotiated.

Velázquez as Court Painter and Court Philosopher

Velázquez enjoyed a close relationship with King Philip IV, who valued him not only as the leading painter of the Spanish court but also as a trusted advisor and intellectual companion. By placing himself so prominently in Las Meninas, Velázquez asserts both his identity as an artist and his rightful place within the courtly hierarchy. His inclusion in the canvas is not an act of vanity but a sophisticated argument about the dignity and intellectual status of painting. Art is not merely craft but a form of knowledge.

The red cross of the Order of Santiago that appears on Velázquez’s chest is a symbolic climax to the argument. This insignia was added after the painting’s completion when the king granted Velázquez admission to the order. Legend holds that Philip himself painted the cross on the canvas, a gesture of royal endorsement that blurs the line between artist and subject, between creation and recognition. The painting thus operates as a manifesto. Velázquez positions himself as a figure who stands between the worlds of manual labor and noble service, asserting that artistic creation can hold its own among the ranks of power.

The Spatial Puzzle

Scholars have long marveled at the painting’s complex spatial construction. Velázquez creates a room that feels both real and oddly uncertain. The foreground is lively and animated. The middle ground recedes into shadow. The background opens into a doorway, where court official José Nieto stands on a staircase, frozen as if caught between entering and exiting. The room is meticulously rendered, yet Velázquez avoids establishing a single stable center of perspective. Instead, he disperses attention across a constellation of focal points.

The result is a dynamic experience of viewing. Our eyes move from the Infanta to Velázquez, from the mirror to the doorway, and from the dwarfs and chaperones to the canvas whose front we cannot see. The painting becomes a theatre of vision. Every gesture, every glance, every shadow signals a network of relationships that remain open to interpretation.

This multiplicity is part of the painting’s enduring magnetism. It resists closure. It resists simplification. Velázquez invites us to participate in the construction of meaning, allowing the painting to unfold differently depending on where we stand and how we look.

Power and Performance

At its core, Las Meninas is deeply concerned with the nature of power. In the highly ritualized world of the Spanish Habsburg court, hierarchy was choreographed with meticulous precision. Yet Velázquez presents this structure not with stiff formality but through a naturalistic tableau that feels spontaneous. The attendants lean in with tender attentiveness. The dwarfs display a lively irreverence. The dog lies peacefully on the floor, half waking, half asleep. The court is revealed as a human environment rather than an abstract emblem of monarchy.

And yet, despite this warmth, the painting reinforces royal centrality. The mirror reminds us that the king and queen are the invisible axis around which everything turns. Even the Infanta’s luminous presence depends on their reflected authority. Velázquez suggests that power is not always loud or ostentatious. It can be mirrored, implied, or refracted. It can exist in the space between what is seen and what is suggested.

A Dialogue with the Future

The influence of Las Meninas reaches far beyond the Spanish Golden Age. In the twentieth century, the painting gained renewed prominence when philosopher Michel Foucault used it as the opening meditation of his book The Order of Things. For Foucault, the painting exemplified a shift in how knowledge and representation were understood. Velázquez’s complex interplay of reflections, gazes, and absences became a metaphor for the instability of meaning in the modern age.

Artists, too, have repeatedly revisited Las Meninas. Pablo Picasso produced an entire series of reinterpretations in 1957, exploring the painting’s structure through a Cubist lens. Salvador Dalí, Antonio de Felguera, and others in Spain engaged with it as a national and artistic touchstone. Each reimagining attests to the painting’s inexhaustible depth. Like a great piece of music that reveals new harmonies at every performance, Las Meninas continues to offer fresh readings with each generation.

Conclusion

Las Meninas is often described as a masterpiece of illusionism, but its brilliance lies less in deception than in revelation. Velázquez exposes the mechanics of looking, the interplay of artist and subject, and the invisible forces that govern representation. He constructs a world that feels real yet trembles with ambiguity. He invites us to share the gaze of royalty while reminding us that vision is always conditioned by power.