How Looking at Art More Slowly Can Change the Way We Think

In a world of constant speed and distraction, slow looking invites us to pause, observe deeply, and reconnect with art. By spending time with images, we rediscover attention, empathy, and a more reflective way of thinking.

In an age of relentless speed, our eyes have learned to skim rather than see. Images flash past us in seconds, captions replace contemplation, and meaning is compressed into bite-sized reactions. We scroll, like, and move on. Yet art, true art, has never been designed for haste. It asks something quietly radical of us: time.

To look at art slowly is not an indulgence or a luxury. It is a skill and a form of attention that can gently reshape the way we think, feel, and relate to the world around us. In slowing down before a painting, sculpture, or photograph, we are not merely consuming culture. We are practising a different way of being.

The Lost Art of Attention

Modern life rewards speed. Productivity, efficiency, and instant response have become virtues. Even in museums, visitors often move quickly from artwork to artwork, pausing just long enough to read a wall label or take a photograph. Studies suggest that the average museum-goer spends less than thirty seconds in front of a single artwork. In that brief moment, we may register the subject, the style, perhaps the artist’s name, and then we move on.

But attention is not neutral. The way we look trains the way we think. When our attention is fragmented, our thoughts follow suit. Slow looking, deliberately spending extended time with a single work of art, offers an antidote. It reintroduces patience into perception and depth into understanding.

What Is Slow Looking?

Slow looking is exactly what it sounds like: the practice of spending sustained, focused time with an artwork, often several minutes or longer. There is no requirement to understand the piece and no need for specialised knowledge. Instead, the emphasis is on observation, curiosity, and openness.

Museums and educators across the world have embraced slow looking as a tool for learning, wellbeing, and inclusion. It encourages viewers to notice details, question assumptions, and remain present with uncertainty. Importantly, it shifts authority away from the expert and returns it to the viewer’s lived experience.

From Seeing to Thinking

When we slow down our looking, something subtle but powerful occurs. The mind begins to move differently.

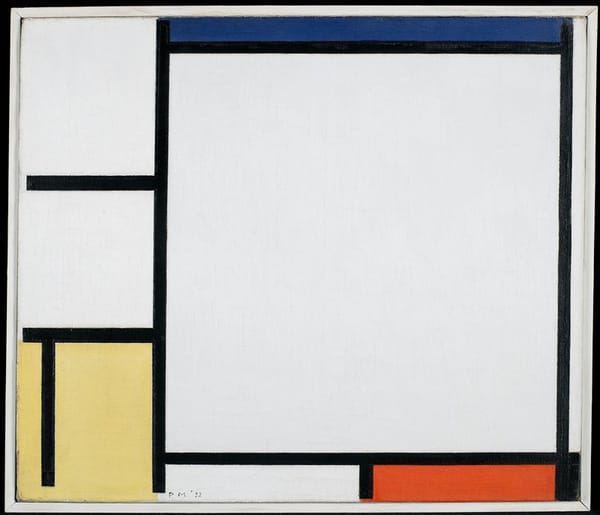

At first, we notice the obvious: colour, scale, subject matter. Then, gradually, smaller details emerge. A brushstroke that feels restless, a figure half-hidden in shadow, a space that seems deliberately unresolved. These observations invite questions rather than answers. Why did the artist choose this moment? What mood is being created? What am I feeling, and why?

This process mirrors deeper cognitive skills such as critical thinking, empathy, and reflection. Instead of seeking immediate conclusions, we learn to sit with ambiguity. In a world increasingly uncomfortable with nuance, this is no small gift.

Art as a Training Ground for Empathy

Slow looking also nurtures empathy. When we spend time with an artwork, particularly one depicting human experience, we are asked to step outside ourselves. A portrait becomes more than a likeness. It becomes a presence. A photograph becomes more than documentation. It becomes a moment of shared humanity.

By lingering, we allow ourselves to imagine other lives, contexts, and emotions. We become attuned to difference without rushing to judgement. This capacity to observe without immediately categorising is essential not only in art, but in how we relate to people, ideas, and cultures beyond our own.

The Neuroscience of Slowing Down

There is growing evidence that slow, attentive engagement has tangible effects on the brain. Extended observation activates areas associated with focus, memory, and emotional processing. It lowers stress responses and encourages a state similar to mindfulness.

Unlike passive scrolling, which often overstimulates and exhausts, slow looking is restorative. It invites the nervous system to settle. This may explain why many people describe feeling calmer, more grounded, and more connected after spending unhurried time with art.

In this sense, art becomes not only an object of beauty or meaning, but a medium for mental clarity.

Learning Without Intimidation

One of the most transformative aspects of slow looking is its accessibility. Traditional art education can feel intimidating, weighted with terminology and historical frameworks. Slow looking offers a different entry point, one based on personal observation rather than prior knowledge.

You do not need to know when a painting was made to notice how it makes you feel. You do not need to understand technique to recognise tension, joy, or stillness. Meaning unfolds through engagement, not instruction.

This approach has proven especially powerful in classrooms, community spaces, and healthcare settings, where participants may feel excluded from formal art discourse. Slow looking reminds us that art belongs to everyone who takes the time to see it.

A Counterpoint to Digital Life

Our digital habits encourage constant novelty. The algorithm rewards what is immediate, familiar, and emotionally reactive. Slow looking, by contrast, asks us to resist distraction and remain with a single image, even when it does not instantly gratify.

This resistance is quietly radical. It retrains attention in a way that carries over into daily life. Conversations become deeper. Reading becomes more immersive. Even moments of silence feel less uncomfortable.

By practising sustained attention with art, we reclaim a capacity that modern life steadily erodes.

How to Practise Slow Looking

Slow looking does not require a museum membership or a quiet gallery. It can be practised anywhere.

Choose one artwork, online or in person, and commit to spending at least five minutes with it. At first, this may feel surprisingly long. Allow your gaze to wander slowly across the surface. Notice what draws you in and what you initially resist.

Ask simple questions. What do I see? What details emerge over time? How does this make me feel? Has my response changed since I began looking?

There are no correct answers. The value lies in the act of sustained attention itself.

Art and the Ethics of Time

To look slowly is also to make an ethical choice. It signals respect for the artist’s labour, for the complexity of the work, and for our own capacity to engage deeply. In a culture that often treats images as disposable, slow looking restores dignity to both viewer and artwork.

It also challenges the idea that productivity must always be measurable. Time spent with art may not result in a tangible outcome, yet its impact is profound and lasting. It reshapes inner landscapes rather than external metrics.

Changing the Way We Think

Slow looking changes not only how we see art, but how we think. It fosters patience in place of urgency, curiosity instead of certainty, and reflection over reaction. These are not merely aesthetic virtues. They are cognitive and ethical ones.

As we approach an increasingly complex future, the ability to pause, observe, and hold multiple perspectives will matter more than ever. Art, viewed slowly, offers quiet training for this kind of thinking.