Did Van Gogh Really Cut Off His Whole Ear? Debunking the Story

For over a century, the story of Van Gogh cutting off his entire ear has endured. Yet recent evidence reveals a more human truth about the artist’s suffering, resilience, and extraordinary capacity for creation.

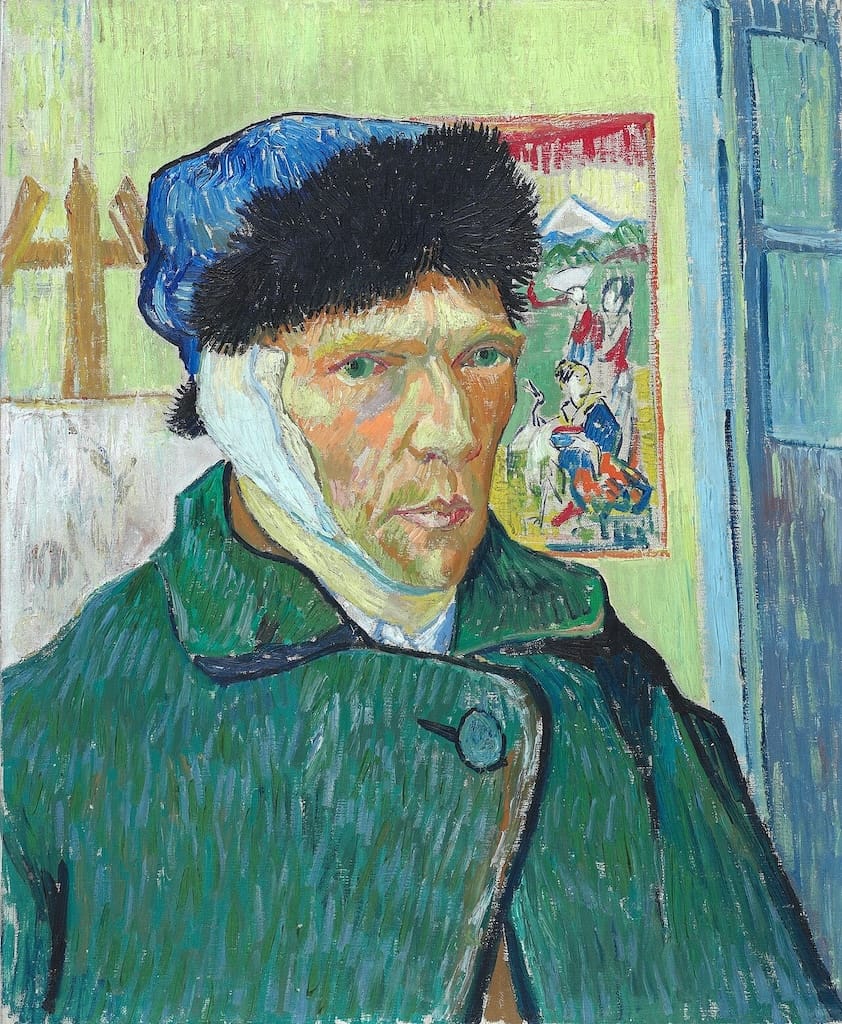

Few artists have inspired as many myths as Vincent van Gogh. The tale of the tormented genius who cut off his ear has become so deeply ingrained in popular imagination that it almost overshadows his art. His self-portrait with a bandaged head has become an icon of artistic suffering, while the story behind the bandage is often repeated in simplified form: Van Gogh, in a fit of madness, sliced off his entire ear. But is this dramatic version true? Recent research and historical documents suggest that the reality is far more complex, nuanced, and deeply human.

A Myth Born of Madness and Romanticism

The story of Van Gogh’s self-mutilation is one of the most sensational anecdotes in art history. It has been used for decades to symbolise the intersection of genius and insanity, of artistic passion pushed to the brink. Yet, as with many myths, it was shaped by the press, by Van Gogh’s own correspondence, and by the cultural fascination with the “mad artist” archetype that emerged in the early twentieth century.

The event in question took place in Arles, southern France, in December 1888. Van Gogh had invited fellow painter Paul Gauguin to live and work with him at the Yellow House, hoping to establish an artists’ collective. Their time together was intense but fraught with tension. Both were strong-willed, passionate personalities with very different artistic visions. Gauguin was cerebral and self-assured, while Van Gogh was emotional and idealistic. Their creative partnership lasted just two months before it imploded.

On the night of 23 December, after a heated argument, Gauguin stormed out. Hours later, Van Gogh allegedly took a razor to his ear. The next morning, he was found unconscious and bleeding at his home, and soon after admitted to hospital. Gauguin left Arles immediately, never to see Van Gogh again.

What Did He Really Cut Off?

For years, it was assumed that Van Gogh had severed his entire ear. Early biographers, perhaps eager for a sensational story, reported as much. However, this version began to unravel when historians and forensic researchers examined primary sources more carefully, particularly the letters written by Van Gogh and his brother Theo, as well as medical records from the Arles hospital.

The most credible evidence indicates that Van Gogh did not remove his entire ear, but rather a portion of it, most likely the lower lobe. A doctor named Félix Rey, who treated Van Gogh, even drew a diagram showing the extent of the injury. The sketch, rediscovered in 2009 in a private collection, shows that only part of the ear was removed, not the whole structure as popular legend suggests.

Van Gogh’s own letters corroborate this version indirectly. He never explicitly describes the injury in detail, but his words reveal a man horrified by what he had done and ashamed of his mental instability. Writing to his brother Theo in January 1889, he referred to “the accident with my ear,” a deliberately understated phrase that hints at both physical and psychological trauma. He spoke of feeling “terribly confused” and “sick with remorse.” Such phrasing implies a partial injury that was painful and serious, but not the total severing described in myth.

What Triggered the Incident?

While the exact cause of Van Gogh’s breakdown remains debated, most scholars agree that it was the result of an accumulation of factors: overwork, poor nutrition, heavy alcohol use, and psychological strain. He was likely suffering from a form of mental illness that modern psychiatrists have variously diagnosed as bipolar disorder, temporal lobe epilepsy, or schizoaffective disorder.

The fight with Gauguin seems to have been the immediate trigger. In Gauguin’s later account, he claimed that Van Gogh had threatened him with a razor before turning it on himself. Whether this version is entirely accurate is uncertain, but what is clear is that Van Gogh’s emotional instability had reached a breaking point. His relationship with Gauguin, once seen as his chance for artistic companionship, had disintegrated into confrontation and despair.

The Infamous Delivery to the Brothel

One of the most enduring details of the story concerns what Van Gogh did after cutting his ear. According to police reports, he wrapped the severed piece in paper and delivered it to a woman named Rachel, who worked at a nearby brothel. When the police later found him at home, bleeding and unconscious, he was taken to the hospital and placed under care.

This bizarre act has provoked endless speculation. Some interpret it as a gesture of affection, since Van Gogh was known to frequent the brothel and had a soft spot for Rachel. Others see it as symbolic, a form of penance or an attempt to externalise his anguish by giving away a literal part of himself. Whatever the motive, the act was not one of theatrical madness but of profound despair and confusion. It revealed a man struggling to cope with loneliness, artistic frustration, and psychological instability.

The Aftermath

After the incident, Van Gogh remained hospitalised for several weeks under the care of Dr. Rey, whose compassion and patience were instrumental in his recovery. He later painted the doctor’s portrait as a gesture of gratitude. When he returned to the Yellow House, the people of Arles were alarmed. His neighbours petitioned to have him evicted, fearing for their safety. Van Gogh himself realised that his mental health was deteriorating. By May 1889, he voluntarily admitted himself to the asylum at Saint-Rémy-de-Provence.

It was during this period of confinement that he created some of his most luminous and introspective works, including The Starry Night and Irises. His paintings from Saint-Rémy show a striking clarity and beauty that stand in stark contrast to his inner turmoil. Far from a symbol of defeat, the ear incident marked a turning point in his life, a descent that paradoxically led to a surge of creative brilliance.

How the Myth Grew

So how did the story of Van Gogh cutting off his entire ear become so widespread? The answer lies partly in early twentieth-century romanticism and the fascination with the “suffering artist” trope. The image of Van Gogh as a martyr to his art was fuelled by sensationalist journalism and later by dramatizations in film and literature.

Irving Stone’s 1934 novel Lust for Life and the subsequent 1956 film adaptation starring Kirk Douglas cemented the myth in the public imagination. These portrayals emphasised drama over accuracy, presenting the act as a moment of total self-destruction. It became emblematic of the idea that artistic genius and insanity were inseparable, a notion that continues to shape how we view creative figures today.

The reality, as it often is, is more nuanced. Van Gogh’s act was not a deliberate performance but a tragic cry for help. He was not a madman romanticising his suffering but a vulnerable human being battling forces he could not control.

The Ear as Symbol

In the end, the story of Van Gogh’s ear, whether whole or partial, remains powerful precisely because of its symbolism. It encapsulates the tension between creativity and fragility, passion and pain. Yet to focus solely on the act itself risks reducing Van Gogh to his suffering, rather than celebrating the extraordinary vision he produced in spite of it.

His self-portrait with the bandaged ear, painted in early 1889, is not a picture of defeat. It is one of resilience. In it, he looks weary yet composed, his gaze steady and introspective. Behind him hang a Japanese print and a bright green wall, suggesting renewal and aesthetic curiosity. Even at his lowest point, Van Gogh’s artistic instinct to transform pain into beauty never left him.

Revisiting the Legend

Did Van Gogh really cut off his whole ear? No. The evidence shows he only removed part of it, likely in a moment of confusion and despair. But the persistence of the myth speaks to something deeper: our need to make sense of genius through stories of sacrifice and suffering. In unravelling the legend, we do not diminish Van Gogh’s humanity; we restore it.