Cyrus J. Guzder: A Legacy of Visionary Leadership, Art Patronage, and Heritage Conservation

Cyrus J. Guzder reflects on his pioneering role in India's logistics industry, his deep connection with art collector Jehangir Nicholson, and his enduring efforts in heritage conservation, offering valuable advice for aspiring artists and entrepreneurs.

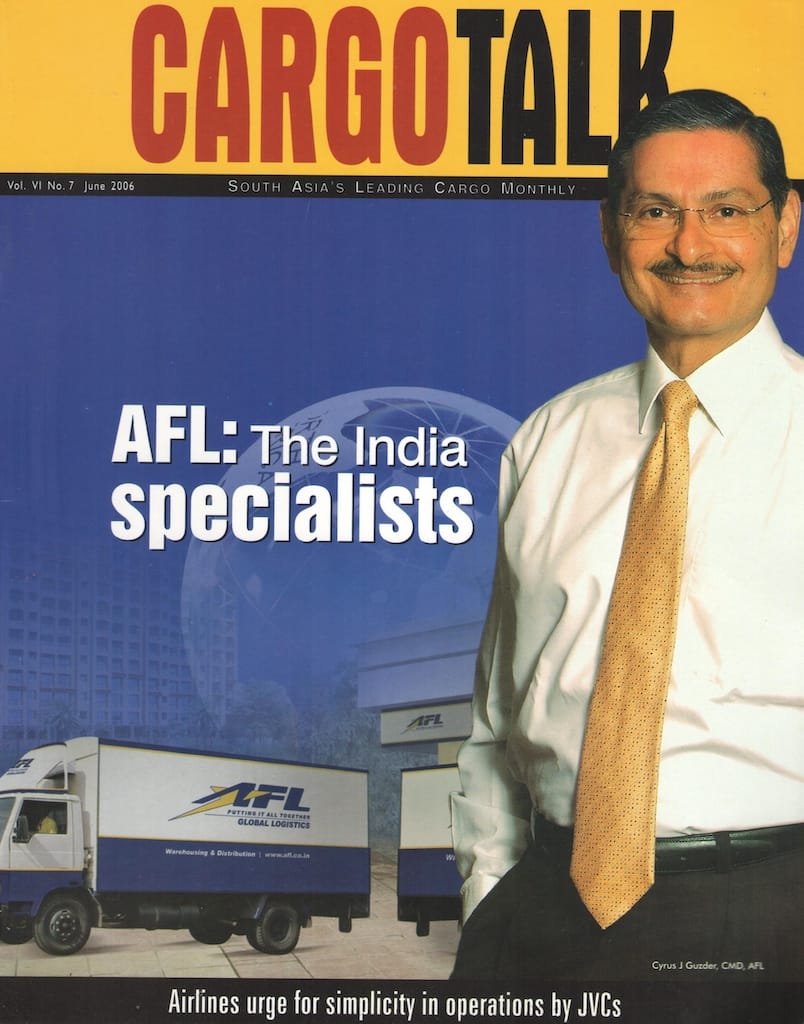

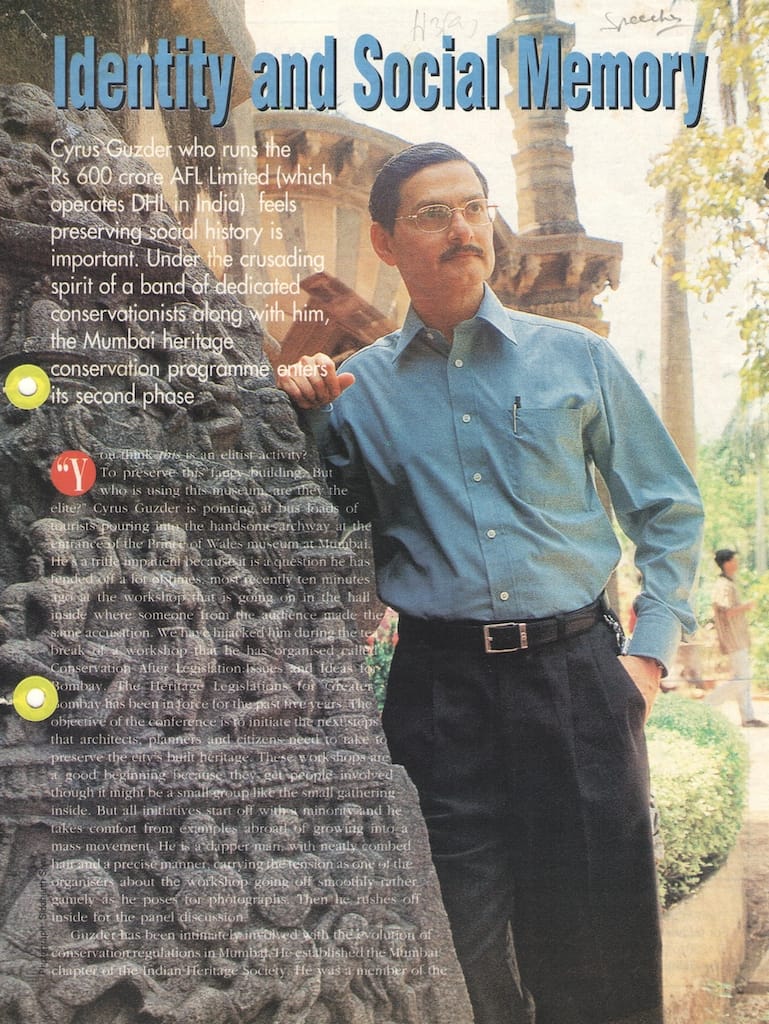

Cyrus J. Guzder is a multifaceted leader whose contributions span across business, environmental conservation, and cultural preservation. As the Chairman and Managing Director of AFL Private Limited, Guzder played a pioneering role in introducing international air courier services to India, steering DHL Worldwide Express for over 25 years. His distinguished career includes directorships on the boards of iconic companies like Air India, BP India, and Tata Infomedia.

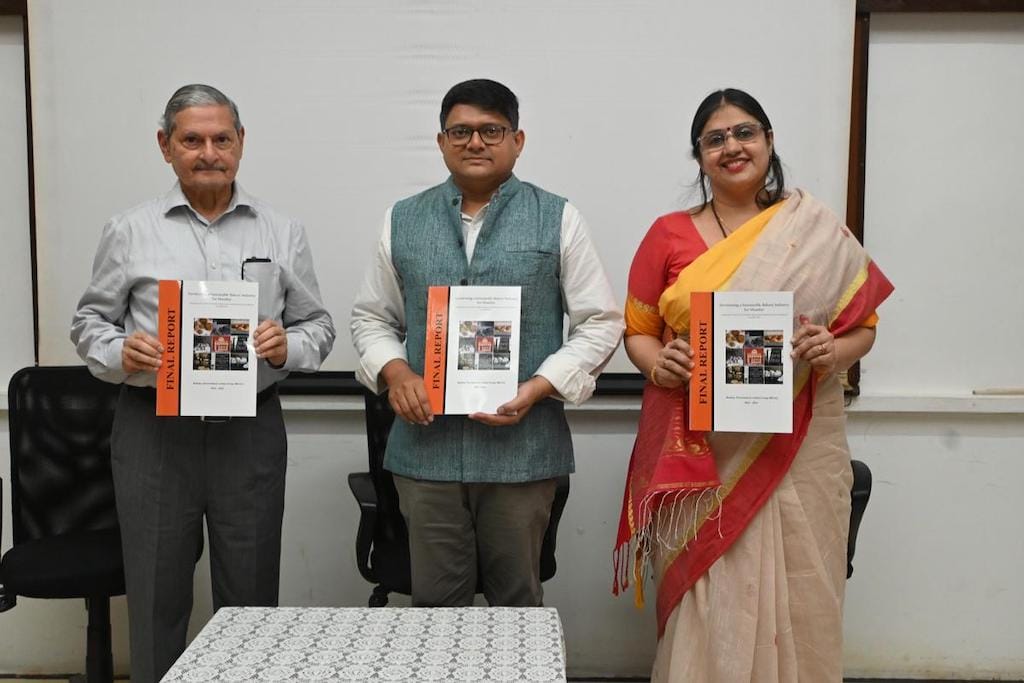

Beyond the corporate world, Guzder has been a stalwart advocate for heritage conservation, currently President of the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG) and establishing key chapters of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH).

A graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, with a Master’s degree in Economics and Oriental Studies, Guzder’s legacy is marked by his unwavering commitment to innovation, cultural preservation, and public service. In this interview, he delves into his relationship with the late art collector Jehangir Nicholson, his role in safeguarding India’s architectural heritage, and his vision for the future of art and conservation.

Nikhil Sardana: You've led a distinguished career, from Chairman and Managing Director of AFL Private Limited to founding director of the Indian Institute for Human Settlements. You've also served on the boards of several notable companies. Could you share insights into the diverse sectors you've worked in—such as transportation, logistics, and banking—and how these experiences have influenced your approach to business management?

Cyrus J. Guzder: My journey began at ICICI, which was then a development bank focused on disbursing World Bank funds to private industries in India. This early experience provided me with a strong foundation in finance under the guidance of mentors like Suresh Nadkarni, who later became ICICI’s Chairman, and Noshir Soonawala, a trusted financial advisor to Ratan Tata. Their mentorship helped shape my understanding of business management, emphasizing the importance of not just disbursing funds but building businesses.

My transition to the family business, Air Freight Limited (later re-named as AFL Private Limited), was gradual. My father never pressured me to join, but when I did, I started from the ground up, learning every aspect of the business. This hands-on experience was crucial in understanding the intricacies of both the air freight and travel industries. For instance, I spent nights at the airport handling cargo, which gave me a deep appreciation for the operational challenges involved in logistics.

In the 1970s, DHL approached us to represent them in India. At the time, the concept of courier services was unknown here. We started with a single customer and one daily shipment, but the service quickly revolutionized the industry by providing time-definite deliveries to destinations abroad. This was especially crucial for sectors like banking, where timely delivery of negotiable documents was vital. By the late 1980s, DHL had become the leading express service provider in India, disrupting traditional postal and air cargo systems.

These experiences taught me the value of adaptability and the importance of understanding the unique challenges of each industry. Whether in logistics, travel, or finance, the key to success has always been a focus on service quality and innovation. These principles have guided my approach to business management throughout my career.

NS: As someone deeply involved in the business world, how did your relationship with Jehangir Nicholson influence your perspective on art and culture?

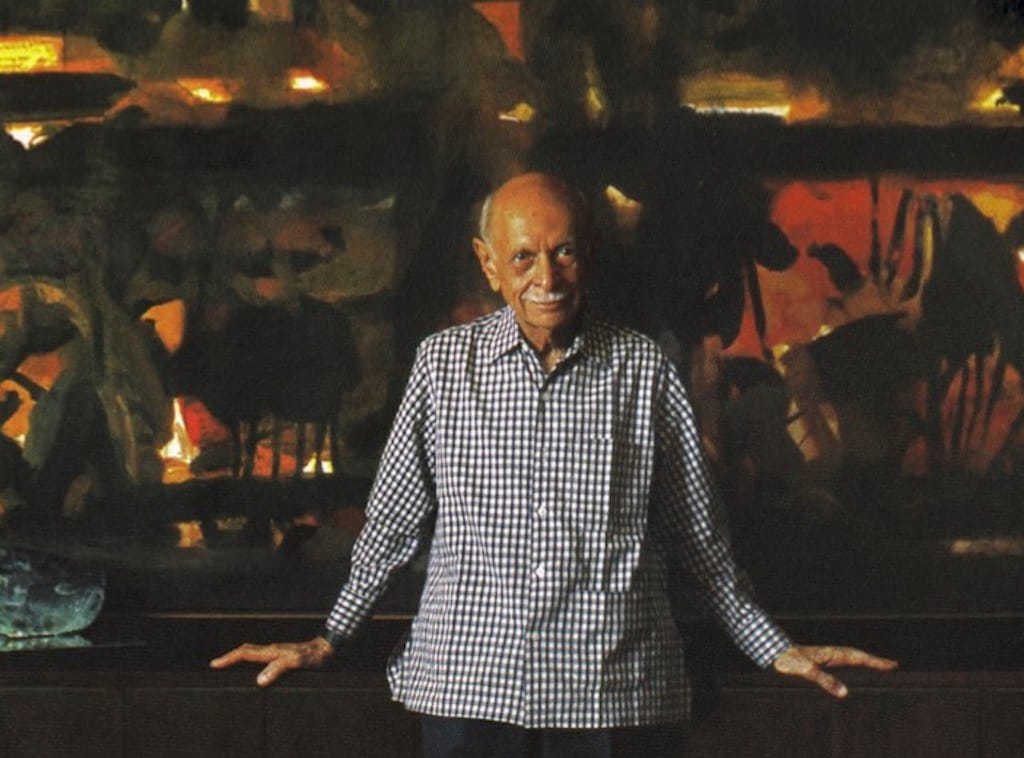

CJG: Jehangir Nicholson was more than just a godfather to me—he was a father figure, especially when my parents were away. He would often stay with us, and I still remember his deep baritone voice singing us to sleep. Jehangir was a complex individual, deeply affected by the early loss of his wife, which led him to immerse himself in various passions, including photography, motor car racing and, eventually, art.

His interest in art began somewhat incidentally. Initially, he was more focused on photography and collecting occasional paintings as a member of the Rotary Club of Bombay. However, his serious immersion into art began when he met Laxman Shrestha, an artist who became a mentor to him. Laxman taught him how to observe and appreciate art, focusing on aspects like colour, form, and abstraction. This mentorship had a profound impact on Jehangir, and he went on to amass a significant art collection, which included works by some of the most prominent artists of the time.

As his “godson” (as he liked to call me), I was indirectly influenced by his passion for art. While I didn’t initially share his deep interest, my exposure to his collection and the artists he associated with gradually deepened my appreciation for modern art. Jehangir's dedication to preserving and showcasing his collection for the public’s enjoyment was a mission that I felt compelled to carry forward after his passing.

NS: Jehangir Nicholson left his vast art collection to you and his lawyer, with instructions to find a home for it. What were the challenges you faced in fulfilling this responsibility?

CJG: Jehangir's Will explicitly instructed us to find a permanent home for his collection, ensuring it would be available for the public to enjoy. However, this was no easy task. The collection was vast—over 750 canvases, 150 objets d’art, and numerous drawings on paper. Finding a space that could accommodate such a diverse and extensive collection was challenging, especially in a city like Bombay, where real estate is scarce and expensive.

After his passing, we had to first locate all the pieces, which were scattered across various locations. Jehangir's trusted servant, Kartik, played a crucial role in helping us track down the paintings. Many were stored in unconventional places—under beds, on top of cupboards, and in different galleries. The next challenge was finding an appropriate space to display them. Jehangir had spent his last years searching for a suitable location in Bombay but had not found one by the time of his death.

As a trustee of the Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya (formerly the Prince of Wales Museum), I realized that this institution could potentially house the collection. However, there was initial scepticism about placing modern paintings in a museum primarily known for antiquities. It was only after discussions with Dadiba Pundole, a close friend of Jehangir and a significant figure in the art community, and with the enthusiastic support of the Museum’s Director – General, that we decided to take up a smaller space in the Museum. This allowed us to frequently rotate items in the collection and keep the exhibitions fresh, ensuring that the public could enjoy a variety of works over time.

NS: Your involvement in heritage and environmental conservation is well-known. How do you see the intersection between environmental protection and art preservation?

CJG: The intersection between environmental conservation and art preservation is quite significant. Both involve protecting something valuable—whether it’s a natural landscape or a piece of cultural heritage—from degradation and loss. My involvement in heritage conservation began with the Bombay Environmental Action Group (BEAG), which I joined from its earliest days, with Shyam Chainani, Ashok Advani, and the late Darryl D'Monte. Our initial focus was on addressing the disorderly development of Bombay, but it soon expanded to include heritage conservation.

One of my early experiences in this field was through a UNESCO project that examined the impact of tourism on India’s monuments. This project highlighted the importance of preserving not just the physical structures but also the cultural significance attached to them. It was a natural progression for me to extend my environmental advocacy to include the conservation of architectural heritage.

For example, when I established the Indian Heritage Society’s Mumbai chapter and later, the Mumbai chapter of INTACH (Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage), our focus was on preserving the city’s colonial buildings. We realized that these structures were at risk of being demolished to make way for new developments. This was deeply troubling, especially considering the historical and architectural significance of buildings like the Rajabai Tower and Victoria Terminus.

Our efforts eventually led to the introduction of heritage regulations in Mumbai, which stipulated that any alterations to heritage buildings had to be approved by a Heritage Conservation Committee. This model set a precedent not only for Mumbai but also for other states like Hyderabad, which later adopted similar regulations.

NS: Given your extensive experience, what advice would you give to young artists and entrepreneurs who are looking to make a mark in their respective fields?

CJG: My own induction into the world of modern art was somewhat accidental, so I might not be the best person to give advice on art. However, one thing I’ve learned from my experiences in both business and art is the importance of passion and perseverance. Whether you’re an artist or an entrepreneur, you need to be deeply committed to your work. It’s not enough to simply have talent or a good idea—you need to be willing to put in the time and effort to see it through.

For young artists, I would say it’s important to find a mentor, someone who can guide you and help you navigate the complexities of the art world. Jehangir Nicholson found such a mentor in Laxman Shrestha, and it had a transformative impact on his life and his approach to art. For entrepreneurs, I would emphasize the importance of adaptability. The business world is constantly changing, and those who can adapt to new challenges and opportunities are the ones who succeed.

NS: Looking back at your career and your contributions to various fields, what do you hope will be your lasting legacy?

CJG: I hope my legacy will be one of service—whether it’s to the business community, the environment, or the world of art and culture. My work with AFL and DHL helped transform the logistics industry in India, and I’m proud of the role we played in that. Similarly, my involvement in heritage conservation has helped preserve some of Mumbai’s most iconic buildings, ensuring that future generations can appreciate their beauty and historical significance.

In the end, I believe that true success is not just about personal achievements but about making a positive impact on the world around you. Whether through business, environmental advocacy, or art preservation, I hope I’ve been able to contribute in a small but meaningful way.