Composition basics: how to arrange elements in a painting

Composition shapes how a painting is seen and felt. This guide explains core principles, from focal points and balance to rhythm and depth, helping artists arrange elements with clarity, intention and expressive impact.

Composition is the quiet architecture of a painting. Long before colour, brushwork or subject matter begin to speak, composition determines how a viewer enters the image, where the eye lingers, and what emotional weight the work ultimately carries. A technically accomplished painting can still feel flat or confusing if its composition is weak, while a simple subject can feel powerful when its elements are arranged with care.

For many artists, composition feels instinctive, but it is built on principles that can be learned, practised and adapted. Understanding these fundamentals does not restrict creativity. Instead, it gives you tools to make deliberate choices rather than relying on chance. This guide introduces the core ideas of composition and shows how they function in painting.

What is composition in painting?

Composition refers to the arrangement of visual elements within the frame of a painting. These elements include shapes, lines, colour, light and shadow, space, and the placement of subjects. Composition governs how these parts relate to one another and to the edges of the canvas.

At its most basic level, composition answers three questions:

- Where should the viewer look first?

- How should their eye move through the painting?

- What mood or meaning should the arrangement reinforce?

A successful composition leads the viewer effortlessly, even unconsciously. When composition fails, the eye wanders aimlessly or becomes stuck, and the painting loses clarity.

The frame and the importance of placement

Before considering complex rules, it helps to recognise that every painting begins with a frame. The edges of the canvas are active forces, not neutral boundaries. Objects placed too close to an edge can feel cramped or accidental, while objects centred without intention can feel static.

Most compositions benefit from asymmetry. Perfect balance is rare in compelling art, because imbalance creates tension, movement and interest. Learning where to place key elements within the frame is the foundation of composition.

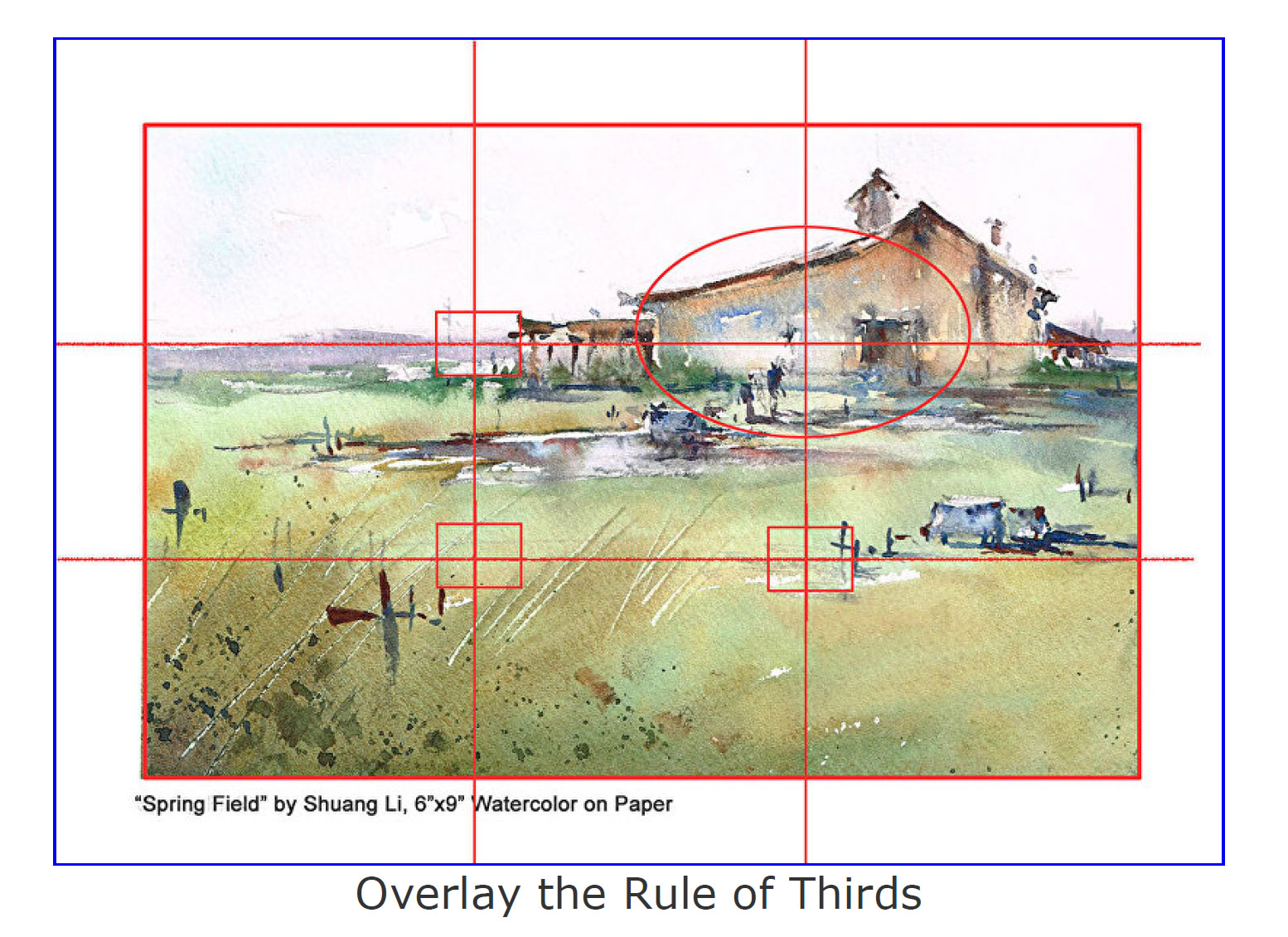

The rule of thirds

The rule of thirds is often the first compositional guideline artists encounter, and for good reason. If you divide the canvas into three equal sections horizontally and vertically, you create a grid with four intersection points. Placing focal points along these lines or intersections tends to produce a more dynamic image than centring everything.

In landscape painting, the horizon often sits along the upper or lower third rather than directly in the middle. In figurative work, eyes or faces frequently align with a third line. The rule of thirds works because it reflects how viewers naturally scan images.

That said, it is a guideline, not a law. Many great paintings break it deliberately. The value of the rule lies in understanding why it works, so that deviation becomes a conscious choice rather than an accident.

Focal points and visual hierarchy

Every painting needs a focal point, a place where the viewer’s eye is drawn first. This does not mean there can be only one area of interest, but there should be a clear hierarchy.

Focal points can be created through:

- Contrast in light and dark

- Strong colour against muted surroundings

- Sharp edges surrounded by softer forms

- Isolated or recognisable shapes

Once the main focal point is established, secondary areas support it. If too many elements compete equally for attention, the painting feels noisy. If no element stands out, the painting feels vague. Composition is largely the art of deciding what matters most.

Leading lines and directional movement

Leading lines are visual pathways that guide the viewer’s eye through the painting. These can be literal, such as roads, rivers, fences or architectural edges, or implied, such as the direction of a gaze, a pointing arm, or a sequence of repeated shapes.

Diagonal lines tend to create energy and movement, while horizontal lines feel calm and stable. Vertical lines suggest strength or stillness. Curved lines often feel organic and graceful.

Effective compositions often combine several types of lines, subtly directing the eye from the focal point to secondary areas and back again. When done well, this movement feels natural rather than forced.

Balance: symmetry, asymmetry and visual weight

Balance in composition is about visual weight, not mathematical equality. Dark colours, saturated hues, complex textures and detailed forms carry more weight than pale, simple or empty areas.

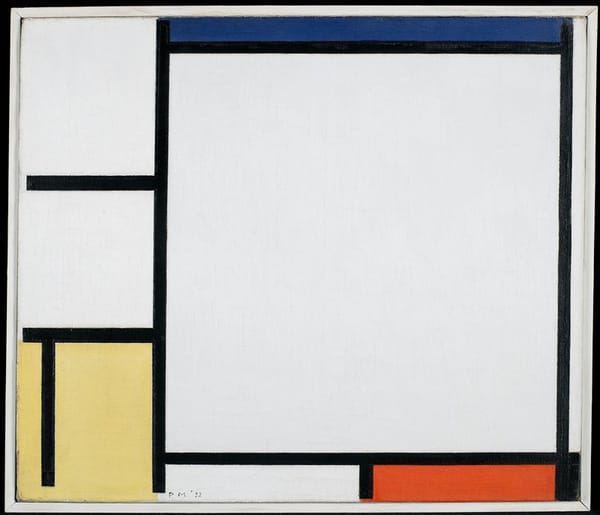

Symmetrical compositions, where elements mirror each other, can feel formal, ceremonial or serene. They are common in religious art and classical portraiture. Asymmetrical compositions rely on counterbalance, where a large shape on one side is balanced by several smaller or lighter elements on the other.

Negative space plays a crucial role here. Empty or quiet areas allow the eye to rest and give weight to what surrounds them. Learning to value what is not painted is as important as mastering what is.

Using light and contrast to shape composition

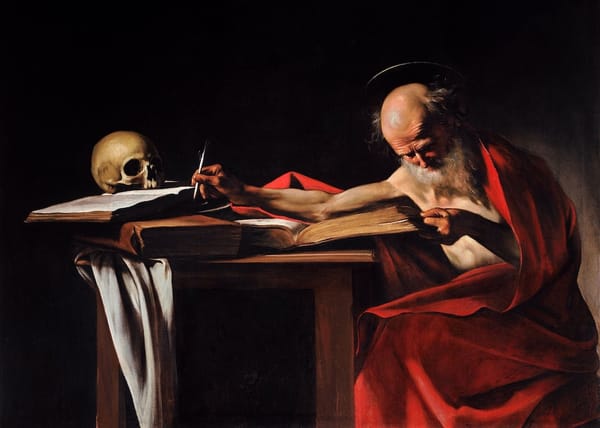

Light is one of the most powerful compositional tools. High contrast areas attract attention, while low contrast areas recede. Painters have long used chiaroscuro, the dramatic contrast between light and shadow, to create focus and depth.

Ask yourself where the light is strongest and why. Does it reinforce the narrative or emotional centre of the painting? Are secondary areas intentionally subdued?

Even in abstract work, contrast in tone or colour often functions as a compositional anchor. Without variation in contrast, paintings risk becoming visually flat.

Depth, overlap and spatial organisation

Creating a sense of depth helps guide the viewer through the picture plane. Overlapping shapes immediately suggest spatial relationships. Size variation, atmospheric perspective and diminishing detail also reinforce depth.

Foreground elements often have sharper edges and richer detail, while background elements are softer and simpler. This hierarchy prevents confusion and strengthens composition.

Even when working on a flat or decorative surface, conscious spatial organisation helps maintain clarity and intention.

Rhythm and repetition

Repetition of shapes, colours or lines creates rhythm, much like music. Rhythm leads the eye across the surface and unifies the painting.

Too much repetition can feel monotonous, so variation is key. Changing scale, spacing or colour keeps the pattern alive. Many painters establish a visual motif and then subtly disrupt it to maintain interest.

Rhythm is especially important in abstract and semi-abstract work, where composition replaces recognisable subject matter as the primary structure.

Breaking the rules with intention

Many of the most compelling paintings in art history break established compositional rules. What separates these works from unsuccessful ones is intention. The artist understands the convention and chooses to disrupt it for expressive or conceptual reasons.

Centring a subject can feel confrontational or iconic. Flattening depth can create decorative intensity. Overcrowding the frame can convey chaos or abundance. Once you understand the basics, you gain the freedom to experiment with confidence.

Practising composition

Composition improves through deliberate practice. Useful exercises include:

- Creating small thumbnail sketches before painting

- Limiting a composition to three main shapes

- Reworking the same subject with different placements

- Studying master paintings and analysing how the eye moves

Digital tools can help, but simple pencil sketches are often the most effective way to explore compositional ideas quickly and without pressure.

Conclusion

Composition is not about rigid formulas, but about relationships. It is the conversation between elements, the tension between fullness and restraint, and the path the viewer takes through the work. By understanding compositional principles, you learn to see your own paintings more clearly and to make choices that serve both clarity and expression. Mastery of composition does not happen overnight. It develops slowly, through observation, study and repeated experimentation. Over time, these principles become instinctive, allowing you to focus less on rules and more on meaning. When composition works, it disappears, leaving behind a painting that feels whole, intentional and alive.