Caravaggio vs the World: Brawls, Exile, and Masterpieces

Caravaggio revolutionised painting with raw realism and dramatic light, but his life was marked by brawls, exile, and scandal. His turbulent story reveals how conflict and genius collided to produce some of art’s greatest masterpieces.

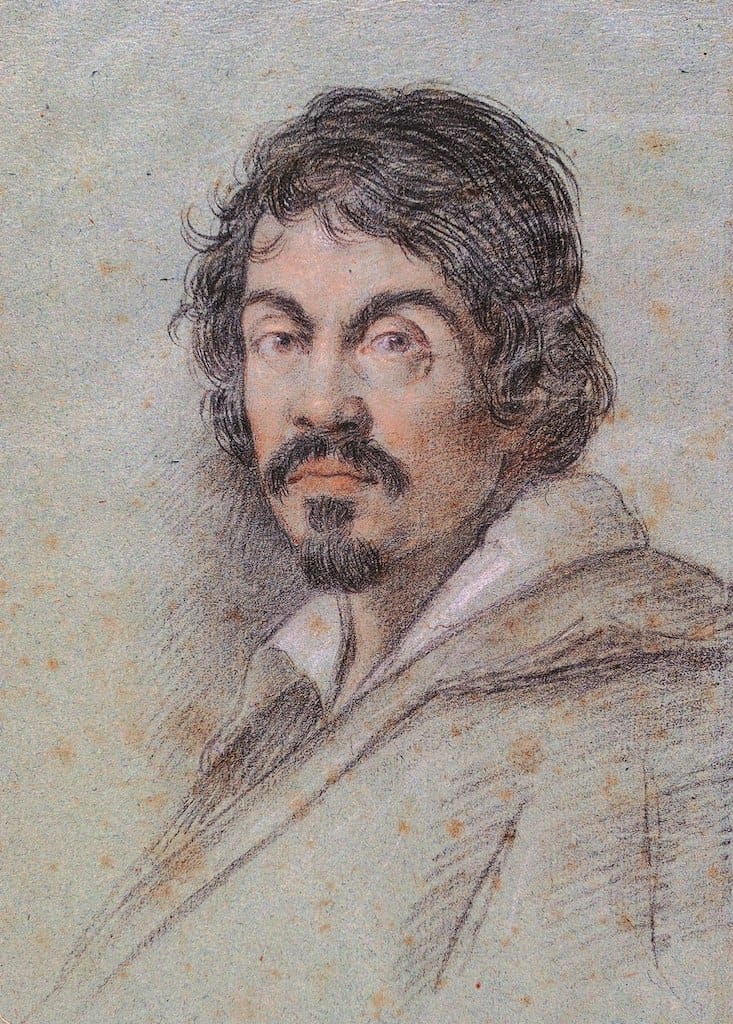

Few artists in history embody the paradox of brilliance and self-destruction quite like Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio. His paintings altered the trajectory of European art, fusing raw naturalism with theatrical intensity, and yet his personal life reads like a litany of scandals, court cases, and acts of violence. While many of his contemporaries carefully cultivated reputations as respectable servants of the Church or noble patrons, Caravaggio seemed almost determined to pit himself against the world. He lived fast, fought hard, and died young – but in the process created some of the most hauntingly beautiful works of the seventeenth century.

This article explores the volatile contrasts of Caravaggio’s life: his revolutionary artistic vision, his notorious reputation for brawls and brushes with the law, his years in exile, and the enduring masterpieces that redefined Western art.

A Revolutionary Vision

Born in 1571 in Milan, Caravaggio came of age in a period of profound upheaval. The Catholic Church, responding to the Protestant Reformation, launched the Counter-Reformation, calling for religious art that was direct, emotional, and capable of moving ordinary worshippers. The official decrees of the Council of Trent demanded clarity, immediacy, and moral force in visual art. Caravaggio took these expectations and turned them into something radically new.

Rejecting the idealised beauty and polished elegance of Mannerism, Caravaggio painted real people with blemishes, dirt, and lived-in humanity. His saints bore calloused hands; his Madonnas looked like working-class women; his apostles were drawn from men off the street. Combined with his revolutionary use of chiaroscuro – the dramatic interplay of light and shadow – Caravaggio’s paintings pulsed with raw immediacy. Works such as The Calling of Saint Matthew (1599–1600) and The Supper at Emmaus (1601) forced viewers into the biblical moment as if it were unfolding before their eyes.

This naturalism shocked some patrons but thrilled others. Caravaggio quickly earned major commissions in Rome, becoming one of the most sought-after painters of his day. Yet his genius was inseparable from his volatility.

The Man Who Picked Fights

Caravaggio’s life in Rome was marked by constant conflict. Contemporary records show an extraordinary number of court summons for assaults, defamation, illegal weapon carrying, and even throwing a plate of artichokes at a waiter. He was notoriously quick to anger, intolerant of slights, and prone to settling disputes with violence.

The streets of late sixteenth-century Rome were dangerous and teeming with rivalries between artists, patrons, and street gangs. Caravaggio immersed himself in this world with characteristic intensity. He lodged with fellow painters but also consorted with gamblers, swordsmen, and prostitutes. His friends were often outlaws; his enemies numerous.

His clashes with fellow artists are legendary. Giovanni Baglione, one of his rivals, accused Caravaggio of circulating defamatory poems about him. Other disputes degenerated into street fights. Caravaggio’s arrogance matched his talent – he knew he was revolutionising painting and could scarcely conceal his disdain for those who painted in more traditional styles.

The Fatal Duel

The turning point in Caravaggio’s turbulent life came in May 1606, when a street quarrel escalated into a fatal duel. The details remain debated, but Caravaggio clashed with Ranuccio Tomassoni, a well-connected young man, possibly over a gambling debt or the favours of a woman. The fight ended with Tomassoni dead and Caravaggio wounded.

The consequences were catastrophic. Rome’s justice system could be brutal: Caravaggio was sentenced to death by beheading. With a bounty on his head, he fled the city he had dominated artistically, beginning years of exile that would shape both his work and his legend.

Years in Exile

Caravaggio’s flight took him first to Naples, then to Malta, Sicily, and back again to Naples. Each stage of his exile added new layers of intensity to his art.

In Naples, he produced some of his darkest and most harrowing canvases, including The Seven Works of Mercy (1607), a monumental altarpiece combining multiple acts of charity in a single crowded composition. His style grew ever more stark, his contrasts of light and shadow deeper, his figures ever more wounded and fragile.

In Malta, he sought redemption by joining the Knights of St John. Remarkably, he painted portraits of the Grand Master and was knighted. But even this triumph ended in scandal. Caravaggio was arrested after yet another violent incident, managed to escape from prison, and was expelled from the Order “as a foul and rotten member.”

Sicily offered temporary refuge, and here Caravaggio painted works such as The Burial of Saint Lucy (1608), where the saint’s martyrdom is rendered with devastating simplicity. But he remained restless, moving constantly, as if pursued by his own demons. His return to Naples saw him attacked and badly disfigured, possibly in revenge for old quarrels.

The Final Chapter

By 1610, Caravaggio sought to return to Rome. Supporters were lobbying for a papal pardon. He set out by boat with several of his paintings, but the journey proved fatal. Accounts vary: some suggest he died of fever on the coast of Tuscany; others claim he was murdered. He was only thirty-eight.

Caravaggio’s death was as enigmatic as his life – sudden, violent, and shrouded in uncertainty. Yet his influence had already spread like wildfire.

Legacy of Light and Shadow

Caravaggio’s impact on art was immense. His dramatic realism inspired a generation of “Caravaggisti” across Europe, from Naples to Utrecht. Painters such as Artemisia Gentileschi, Georges de La Tour, and Rembrandt drew upon his stark contrasts of light and shadow and his unflinching humanity.

The Church itself, despite his scandals, continued to value his capacity to move audiences. His works became exemplars of the Counter-Reformation ethos, embodying both theatricality and sincerity.

Modern scholarship often frames Caravaggio as the first great modern painter – not only because of his stylistic innovations but also because of the complex, conflicted humanity his art conveys. Unlike the serene perfection of earlier Renaissance art, Caravaggio’s canvases force us to confront suffering, violence, and doubt. They feel startlingly contemporary.

Caravaggio Against the World

So how should we understand Caravaggio’s volatile life? Was he a doomed genius, unable to control his violent impulses? Or was his art inseparable from the very turbulence that destroyed him?

What is certain is that Caravaggio lived in constant opposition: against rivals, against authorities, against the idealised traditions of art. He embraced contradiction – sinner and visionary, fugitive and innovator. His brawls and exiles were not mere biographical details but echoes of the intensity that infused his art.

In this sense, Caravaggio was always wrestling with the world – and perhaps with himself. His paintings, charged with both brutality and grace, remain his most eloquent answer.