Canvas of Thought: How Philosophy Shapes Visual Art

From Platonic ideals to postmodern deconstruction, artistic practice has long been guided by philosophical enquiry. This exploration uncovers how concepts of beauty, ethics and perception have informed visual art across eras, from antiquity to today.

Philosophy and visual art share a symbiotic relationship that has endured through centuries. From the allegorical frescoes of the Renaissance to the conceptual installations of the twenty-first century, artists have continually turned to philosophical ideas to inform and challenge their practice. Philosophy provides a framework for questioning existence, perception, ethics and society, offering artists fertile ground for creative exploration. Conversely, art gives philosophical concepts tangible form, engaging viewers on emotional and sensory levels. This article examines how key philosophical movements have shaped visual art, and in turn, how artists have used their medium to interrogate and advance philosophical discourse.

Classical Antiquity and the Ideal Form

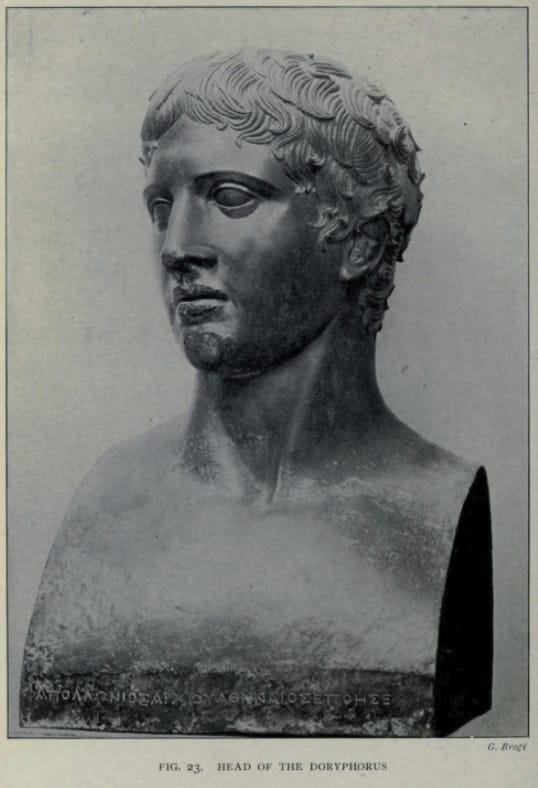

In ancient Greece, the notion of mimesis—the imitation of nature—pervaded both philosophy and art. Plato regarded art as an imitation of an imitation, twice removed from truth, while Aristotle saw it as a means to catharsis and moral education. Visual artists of the era aimed to express the ideal form, believing that beauty lay in harmony, proportion and balance. The sculptural works of Polykleitos, epitomised by his Doryphoros, embody the philosophical quest for an idealised human figure governed by mathematical ratios.

This emphasis on the ideal persisted into Roman art, where philosophical treatises guided portraiture and architectural design. In these early periods, philosophy offered a set of aesthetic principles that artists could measure themselves against, setting a standard that would echo through the Renaissance.

The Renaissance: Humanism and the Revival of Classical Thought

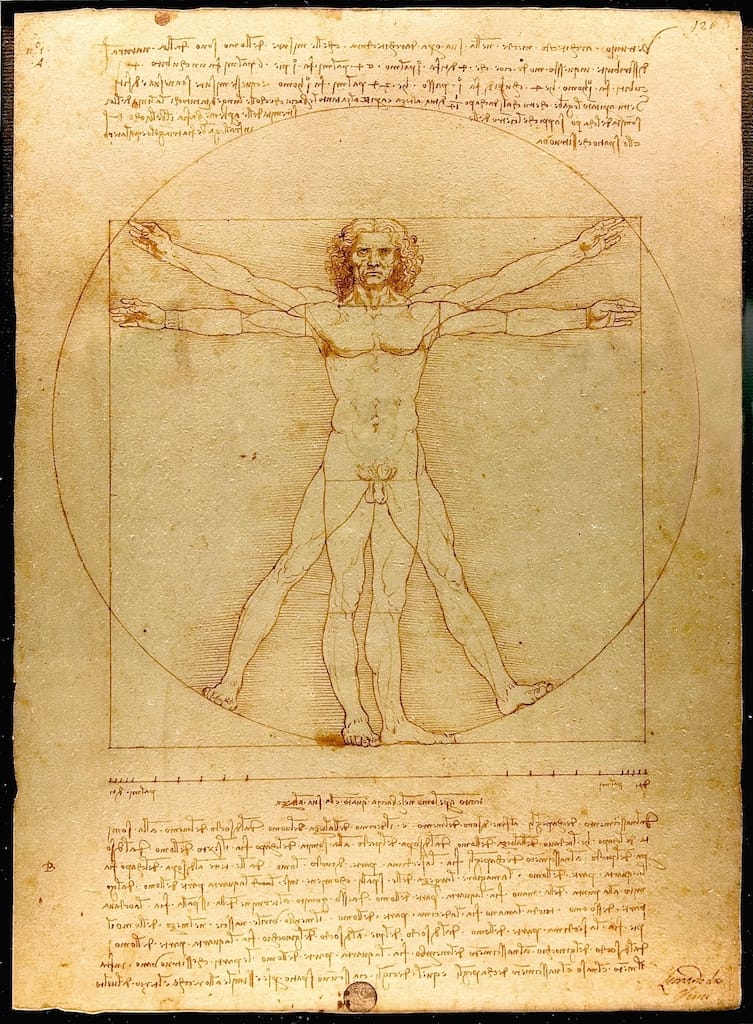

The Renaissance saw a revival of classical philosophy, particularly the humanist belief in the worth and dignity of the individual. Thinkers such as Petrarch and Erasmus emphasised the power of reason, education and personal experience. Artists like Leonardo da Vinci and Albrecht Dürer absorbed these ideas, producing works that celebrated both divine beauty and human emotion.

Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man is more than a study of anatomy; it is a visual manifesto of humanist ideals, combining scientific observation with the search for perfection. Dürer’s engravings often include Latin inscriptions and allegorical references to virtue, reflecting the artist’s erudition and engagement with philosophical texts. Through perspective, chiaroscuro and naturalism, Renaissance art revealed a profound belief in humanity’s capacity to perceive truth and beauty.

Enlightenment Rationalism and the Pursuit of Order

The Enlightenment of the eighteenth century heralded the age of reason. Philosophers such as Descartes, Locke and Kant promoted critical inquiry, empirical observation and the autonomy of the individual mind. This intellectual climate influenced Neoclassical artists, who sought clarity, restraint and harmony in their work.

Jacques-Louis David’s Oath of the Horatii exemplifies Enlightenment ideals. Its clear composition, moral subject matter and disciplined style reflect the philosopher’s faith in rationality and civic virtue. Similarly, Angelica Kauffman’s neoclassical paintings often draw upon classical mythology to illustrate innocence, duty and moral rectitude. In these works, the canvas becomes an arena in which philosophical notions of duty, reason and moral law are played out.

Romanticism: Emotion, Individual Experience and the Sublime

As a counter-movement to Enlightenment rationalism, Romanticism in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries prioritised emotion, imagination and the sublime. Philosophers such as Rousseau, Kant and later Schopenhauer emphasised the limits of reason and the importance of individual feeling. Romantic artists sought to capture the ineffable qualities of nature, the depths of human emotion and the transcendental.

J. M. W. Turner’s storm-tossed seascapes and Caspar David Friedrich’s solitary figures before vast landscapes convey aesthetic experiences that border on the metaphysical. The sublime—nature’s power to overwhelm and inspire awe—became a central motif, echoing Kant’s distinction between the beautiful and the sublime. Romantic art thus became a vehicle for exploring the complexities of feeling, intuition and the human spirit.

Modernism: Critique, Abstraction and Existential Inquiry

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries witnessed seismic shifts in philosophy and art. Positivism, Marxism, Freudian psychoanalysis and existentialism emerged alongside rapid industrialisation and social upheaval. Artists questioned traditional aesthetics, representation and the role of art in society.

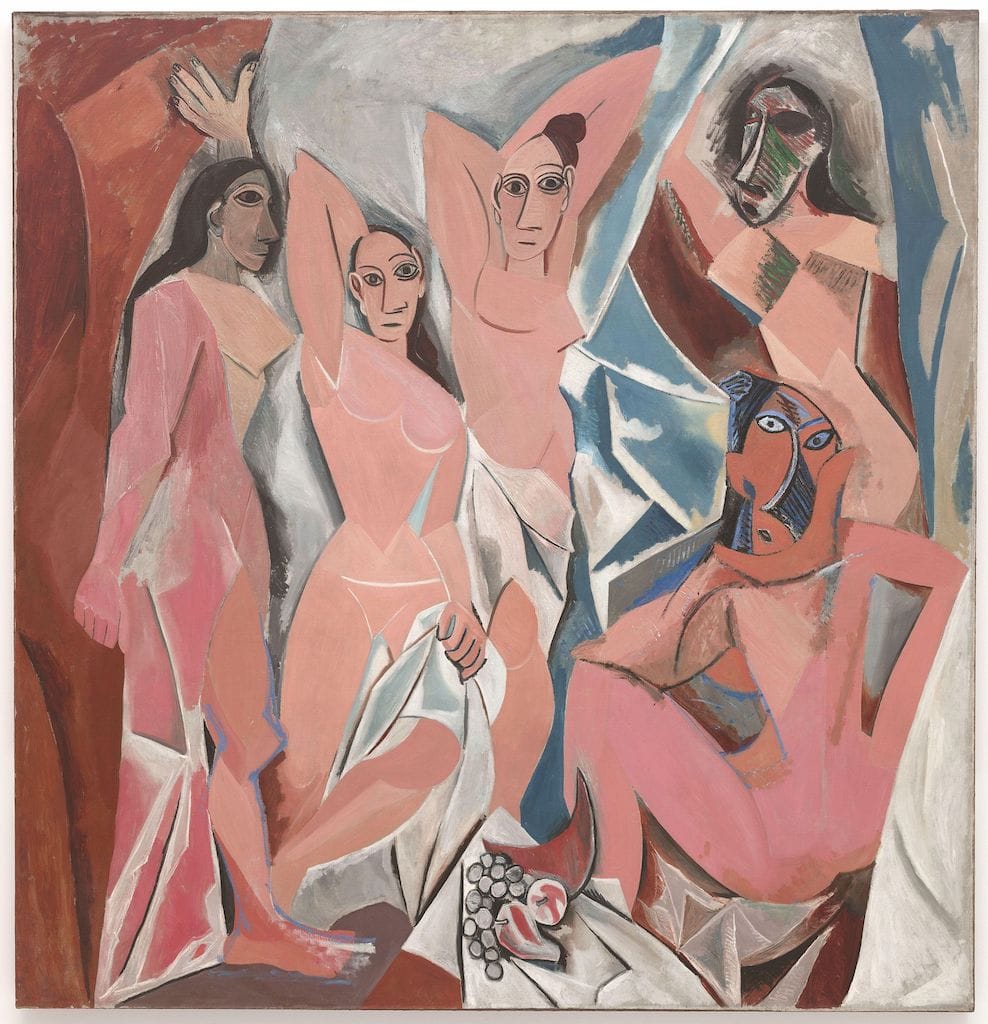

- Cubism, pioneered by Picasso and Braque, deconstructed objects into geometric facets. This fragmentation reflects the contemporary preoccupation with multiplicity, subjectivity and the relativity of perception—a visual analogue to philosophers’ challenge to absolute truths.

- Surrealism, inspired by Freud’s theories of the unconscious, sought to reveal hidden desires and irrational states. Salvador Dalí’s melting clocks in The Persistence of Memory evoke dream logic and the fluidity of time, illustrating how philosophical insights into the mind can manifest as striking visual metaphors.

- Abstract Expressionism, with figures such as Jackson Pollock and Mark Rothko, explored existential themes. Pollock’s action painting embodies the philosophy of being-in-the-world, emphasising process over outcome, while Rothko’s colour-field canvases invite contemplative engagement, aligning with existentialists’ search for individual meaning.

These movements demonstrate how philosophy furnished artists with new ways to interrogate reality, identity and the human condition.

Postmodernism and the Questioning of Meta-Narratives

By the 1970s, postmodern philosophy—from Lyotard’s scepticism of grand narratives to Derrida’s deconstruction—challenged assumptions about truth, authorship and fixed meaning. Visual art embraced pastiche, irony and hybridity, often undermining the notion of original or authentic expression.

- Appropriation art, as practised by Sherrie Levine and Richard Prince, directly engages with postmodern ideas about originality and authorship by re-presenting existing artworks. Their work asks: Who owns an image? What constitutes originality?

- Conceptual art, championed by Joseph Kosuth, places the idea above the aesthetic object. Kosuth’s One and Three Chairs, which displays a chair, a photograph of a chair and a dictionary definition of “chair,” poses philosophical questions about representation and language, echoing Wittgenstein’s investigations into how language shapes thought.

- Relational aesthetics, as theorised by Nicolas Bourriaud, views art as a social exchange. Works by Rirkrit Tiravanija, who invites gallery visitors to share meals he prepares, reflect the postmodern turn towards intersubjectivity and the dissolution of the artist–audience divide.

Postmodern art thus becomes a site of philosophical debate, dismantling established categories and encouraging viewers to question the structures of meaning itself.

Contemporary Dialogues: Ethics, Technology and the Environment

In the twenty-first century, visual art continues to grapple with philosophical challenges posed by technological advancement, globalisation and ecological crisis.

- Bio-art, which uses living organisms as medium, raises bioethical questions about life, creation and manipulation. Artists such as Eduardo Kac, famed for his “GFP Bunny” experiment, provoke debate on the ethical limits of biotechnology and the definition of life itself.

- Digital and generative art, powered by algorithms and artificial intelligence, interrogates concepts of creativity and authorship. Philosophers like Luciano Floridi have begun to explore the ontology of artificial agents, and artists mirror these inquiries through works that evolve autonomously.

- Eco-art and environmental installation pieces challenge the philosophies that have led to ecological degradation. Maya Lin’s What Is Missing? memorialises vanished species and habitats, engaging with deep ecology’s call for a more harmonious relationship between humans and the natural world.

Through these practices, contemporary artists address urgent philosophical questions, reminding us that art remains a crucial arena for negotiating the ethical and existential dilemmas of our age.

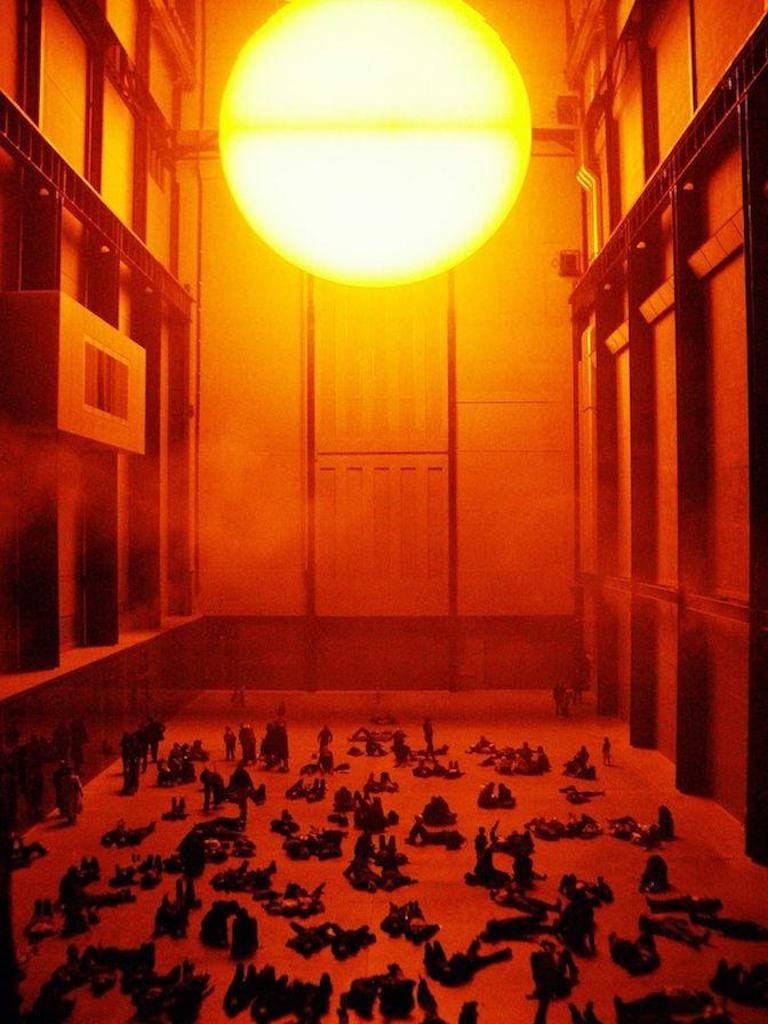

Case Study: Olafur Eliasson’s Experiments in Perception

Olafur Eliasson’s immersive installations provide a compelling example of philosophy informing visual art. His work often explores phenomenology—the study of structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view. In The Weather Project (2003), Eliasson filled Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall with a simulated Sun and fine mist, compelling viewers to confront their own perception of space, light and collective experience. This echoes Merleau-Ponty’s assertion that perception is neither purely subjective nor entirely objective but arises through embodied engagement with the world.

Eliasson’s piece Your Rainbow Panorama (2011), a circular walkway of coloured glass atop a Danish art museum, invites participants to experience shifting hues in relation to the cityscape, illustrating how our sensory filters mediate reality. These installations exemplify how philosophical theories of perception, embodiment and environment can be translated into profoundly affecting visual experiences.

Conclusion

The dialogue between philosophy and visual art is enduring and dynamic. Philosophical ideas offer artists conceptual tools to address questions of beauty, truth, ethics and existence, while art brings these abstractions into the realm of lived experience. From the ideal forms of antiquity and the humanist precision of the Renaissance to the conceptual playfulness of postmodernism and the urgent concerns of contemporary practice, philosophers and artists have worked in tandem to expand our understanding of the world and our place within it.