Can Art Be Taught, or Only Experienced?

Is art learned through classrooms or lived encounters? This essay explores where technique ends and experience begins, arguing that meaningful art emerges from the tension between teaching, intuition, history and personal lived reality and reflection.

The question of whether art can be taught or only experienced has animated debates in studios, classrooms, academies and cafés for centuries. It resurfaces whenever a new art school opens, whenever tuition fees rise, and whenever a self-taught artist achieves public recognition. At its core lies a deeper inquiry about creativity itself. Is art a transferable skill, shaped through pedagogy and practice, or is it something ineffable that emerges through lived experience, intuition and emotional encounter?

The answer, perhaps frustratingly, is not a simple one. Art occupies a space between discipline and instinct, between instruction and discovery. To consider whether art can be taught is also to ask what we mean by teaching, and what we believe art fundamentally is.

The Historical Roots of Teaching Art

Historically, art has almost always been taught. From the ateliers of Renaissance Europe to the guild systems of India and East Asia, artistic knowledge was transmitted through apprenticeship. Young artists learned to grind pigments, prepare surfaces, copy masterworks and internalise proportions long before they were encouraged to invent. Michelangelo trained in the workshop of Domenico Ghirlandaio. Mughal miniature painters worked collectively under court masters. In these systems, teaching was not an abstract theory but a lived process of repetition, observation and gradual refinement.

Yet even within these rigid structures, individuality emerged. The training provided a language, not a voice. What separated the competent from the exceptional was not access to instruction but the ability to absorb, transform and transcend it. Teaching provided the grammar of art, but expression came from elsewhere.

This distinction remains central today.

What Exactly Can Be Taught?

There is little dispute that certain aspects of art can be taught effectively. Technique, for one, is eminently teachable. Perspective, anatomy, colour theory, composition, printmaking processes, digital tools and material handling all benefit from structured instruction. Without guidance, artists often spend years reinventing knowledge that could be transmitted in weeks.

Art history and visual literacy are equally teachable. Learning to see how artists across cultures and centuries have responded to power, faith, identity, technology and trauma enriches an artist’s vocabulary. It situates individual practice within a broader human conversation. Exposure to movements, ideas and critical frameworks sharpens awareness and prevents creative solipsism.

Even habits such as discipline, critique, documentation and professional practice can be taught. Many artists falter not because of lack of talent but because they struggle with consistency, feedback or navigating the art world. In this sense, art education offers scaffolding. It supports the making of art, even if it cannot guarantee its depth.

The Limits of Instruction

Where teaching encounters its limits is in the realm of meaning. No teacher can instruct a student to be honest, vulnerable or courageous in their work. These qualities arise from lived experience, reflection and often discomfort. They are shaped by personal history, social context and emotional risk.

An artwork may be technically proficient yet hollow, while another may be formally awkward but deeply affecting. This difference rarely lies in instruction alone. It lies in how an artist has experienced the world and how willing they are to translate that experience into form.

Art, at its most compelling, is not simply made. It is lived through. Loss, joy, displacement, love, boredom, political unrest, solitude and wonder all leave traces in an artist’s work. These cannot be taught in a classroom, nor should they be. They belong to the unpredictable texture of life.

This is why many artists speak of a turning point outside formal education. A journey, a failure, a relationship, a period of isolation or an encounter with another artwork often catalyses a shift that no syllabus could design.

Experience as a Form of Education

If art cannot be fully taught, it can certainly be experienced, and experience itself is a powerful educator. Visiting museums, encountering unfamiliar cultures, reading widely, listening attentively and observing closely all shape artistic sensibility. Even non artistic experiences, such as working unrelated jobs or navigating bureaucracy, can inform an artist’s understanding of structure, repetition and power.

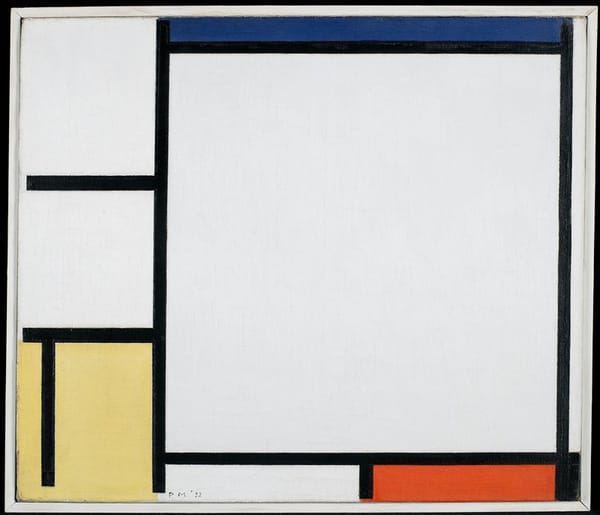

Importantly, experience also includes encountering art itself. Standing before a painting, listening to a performance or moving through an installation offers something that reproduction and explanation cannot. It is here that art resists didacticism. It does not explain itself fully, and it does not need to.

This experiential dimension challenges traditional education models that prioritise outcomes and assessment. Art does not always reveal its value immediately. Its impact may surface years later, quietly influencing how one sees, thinks or feels.

The Role of the Teacher Today

If art cannot be transmitted in its entirety, what then is the role of the teacher? Increasingly, it is not to instruct what art should be, but to create conditions in which art might emerge.

Good teachers do not impose a style or ideology. They ask questions, encourage risk and help students articulate their intentions. They introduce references, challenge assumptions and provide context, but they also know when to step back. Their success is not measured by replication but by divergence.

In this sense, teaching art is less about providing answers and more about sharpening perception. It is about helping students learn how to look, how to listen and how to reflect. These skills extend beyond art making. They shape how individuals engage with the world.

The Myth of the Untaught Genius

Romantic narratives often celebrate the self-taught genius who emerges fully formed, untouched by institutions. While compelling, this myth obscures reality. Even artists without formal training learn through experience, observation and influence. No artist exists in isolation.

Moreover, access to education, whether formal or informal, is uneven. To suggest that art should only be experienced risks excluding those who benefit deeply from structured learning environments. For many, art education provides not only skills but also community, validation and exposure that might otherwise be unavailable.

The question is not whether art schools should exist, but how they can remain porous, reflective and responsive to the lived realities of artists.

A False Dichotomy

Framing art as either taught or experienced presents a false dichotomy. In practice, the most meaningful artistic development arises at the intersection of both. Teaching without experience risks producing work that is clever but detached. Experience without guidance can lead to expression that is sincere but underdeveloped.

The challenge lies in balance. Art education should not aim to manufacture artists, but to equip individuals with tools, contexts and confidence. Experience then animates those tools, filling them with urgency and relevance.

This balance is particularly important today, as digital platforms accelerate production and visibility. The pressure to be seen can eclipse the need to be grounded. Teaching can offer critical pause, while experience provides substance.

Conclusion

So, can art be taught, or only experienced? Art can be taught in parts, but it must be experienced to be fully realised. Teaching offers structure, language and lineage. Experience provides depth, meaning and necessity. Art lives in the space between knowing and feeling, between instruction and intuition. It is shaped by hands that have practised and minds that have wandered. To deny either dimension is to misunderstand the richness of artistic practice.

Perhaps the more useful question is not whether art can be taught, but how teaching can remain open to experience, and how experience can remain receptive to learning. In that meeting point, art continues to find its voice.