Art vs Craft: A False Hierarchy?

The long-standing divide between art and craft is a cultural invention rather than an inherent truth. Contemporary practice reveals how deeply intertwined these forms are and why creativity flourishes when their boundaries dissolve.

For more than a century, the distinction between art and craft has sparked passionate debate. Museums, art schools and cultural theorists have all contributed to a hierarchy that places fine art above craft, as though one were a realm of pure ideas and the other a space of useful objects. Yet this division is not natural. It is a construct shaped by history, economics and institutions rather than an inherent truth about creativity. Today, with artists and makers freely crossing boundaries, it is worth asking whether the hierarchy between art and craft was ever justified.

A Historical Divide

The common belief that art is expressive while craft is functional is deeply ingrained. In many museums, paintings and sculptures are presented as art, while textiles, ceramics and furniture appear in separate galleries. This separation subtly implies that the intellectual or emotional value of a woven or moulded object is somehow lesser.

Yet if we step outside this institutional framing, the idea becomes questionable. Many of the world's most celebrated cultural artefacts would fall under the category of craft in a Western taxonomy. Japanese ceramics, Indian textiles, African masks and Persian carpets all carry profound aesthetic and symbolic depth.

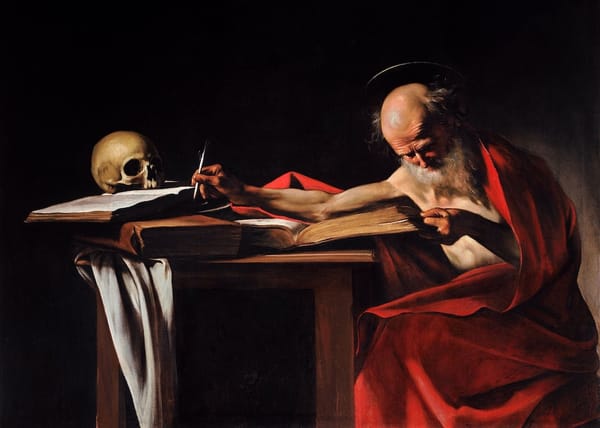

The divide itself is relatively recent. In medieval Europe, painters, sculptors and goldsmiths belonged to guilds, and artistic labour was considered skilled manual work rather than an elevated spiritual calling. The Renaissance elevated the idea of the artist as a visionary individual, and by the nineteenth century academic institutions had solidified a hierarchy that privileged history painting and sculpture over the domestic or utilitarian. This framework later spread globally and often marginalised local craft traditions.

Movements That Challenged the Hierarchy

Throughout history, the hierarchy has been repeatedly contested. The Arts and Crafts Movement, led by William Morris, rejected industrial mass production and championed the value of handwork. Morris believed that beauty and labour were inseparable and that the distinction between artist and craftsperson was arbitrary.

Later, the Bauhaus advanced this unity even further. Under Walter Gropius, students worked fluidly across weaving, metalwork, glass, theatre, painting and architecture. Every discipline was treated as part of a shared creative pursuit rather than a ladder with fixed rungs.

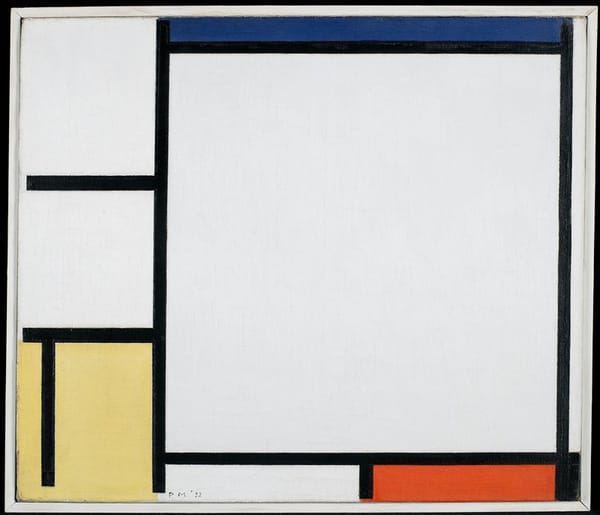

Despite these attempts to break down boundaries, the art world continued to treat craft as secondary through much of the twentieth century. Modernist painting and sculpture were elevated, while ceramics or textiles were often perceived as decorative rather than conceptual.

Contemporary Practice and the Blurring of Boundaries

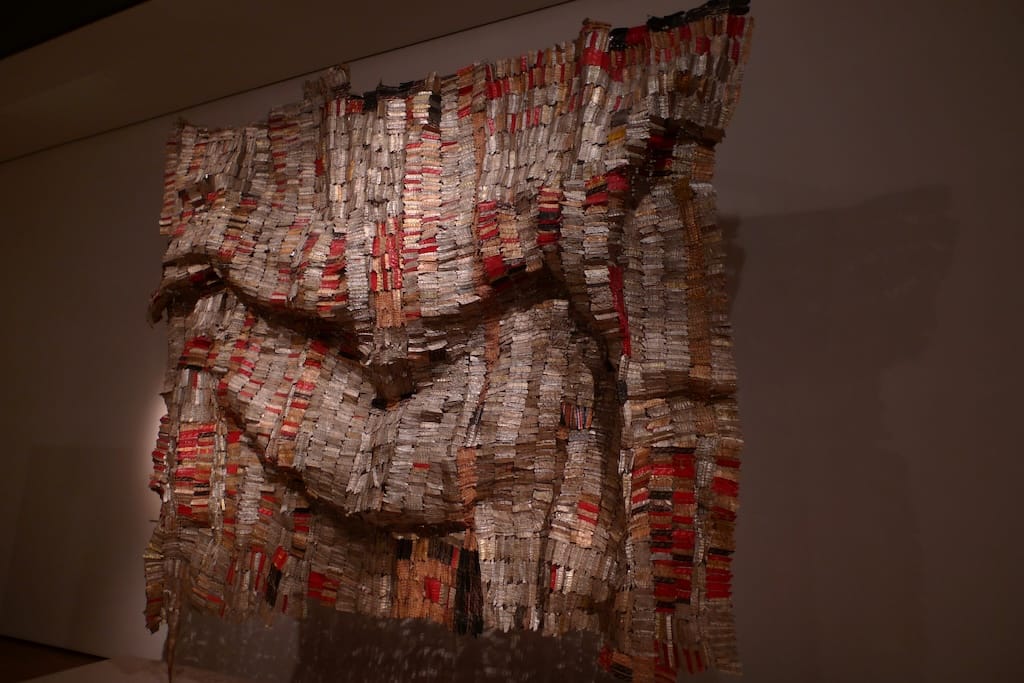

Contemporary artists are now eroding these boundaries with remarkable energy. Sheila Hicks uses fibre to create monumental installations. Grayson Perry elevates ceramics to narrative and political forms. El Anatsui transforms discarded materials into shimmering tapestries. In India, Mrinalini Mukherjee created monumental fibre sculptures that defied categorisation, and many contemporary artists draw from craft traditions in collaboration with artisan communities.

Materials that were once dismissed as lesser are now embraced as sites of conceptual experimentation. A pot is not inherently less artistic than a canvas. A textile can carry political urgency equal to any painting. Museums and biennales increasingly feature craft-based practices, and design galleries have gained prominence in the contemporary art market.

This artwork is a modern interpretation of kente cloth from the artist's native Ghana. It is made up of hundreds of metal bottleneck wrappers, stitched together with copper wire. A close up can be seen in the image on the right. On public display at The British Museum, Department of Africa, Oceania and the Americas. Photo: El Anatsui, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Digital culture adds another dimension. The maker movement, powered by 3D printing and open-source tools, blurs old lines between professional and amateur creativity. Craft has become a space for innovation, community and experimentation, rather than simply tradition.

The Social and Economic Roots of the Hierarchy

Despite progress, the hierarchy persists in subtle ways. Language still reveals ingrained bias. Craft is often associated with modesty or domesticity, and this perception has historically been gendered. Many craft traditions are rooted in women's labour, which has contributed to their marginalisation.

Economics further complicates the divide. The fine art market relies on scarcity, singular authorship and the mythology of the individual genius. Craft practices often involve collective techniques or repetition, which do not fit easily into this model. Yet craft embodies forms of intelligence that are deeply relevant today. These include sustainable production, ethical practice and intergenerational knowledge.

Education too is evolving. Art schools now encourage students to move across media, and craft departments sit alongside fine art programmes rather than beneath them. Many young artists describe themselves as multidisciplinary practitioners rather than identifying with a single material tradition.

Towards a New Understanding of Creativity

When we set aside the hierarchy, creativity appears not as a rigid structure but as a continuum. Skill is no longer seen as mere execution but as a form of thinking. Material intelligence and conceptual depth become inseparable.

A hand-thrown pot can speak of fragility, memory or resistance with as much force as a sculptural installation. A quilt can be a political document. A woven textile can hold ancestral knowledge and contemporary commentary simultaneously.

Rather than asking whether something is art or craft, it is more productive to ask what conversations it initiates, what histories it holds and what emotions it evokes.

Reclaiming Craft as a Site of Meaning

By reconsidering the hierarchy, we discover that craft offers profound insight into cultural memory, sustainability and human touch. Craft is not simply an alternative to art. It is an essential language of making that connects communities, traditions and materials. It creates bridges between past and present and between utility and imagination.

Artists and makers today are not waiting for institutions to rewrite definitions. They are already creating new forms that resist categorisation. Their work invites viewers into a world where boundaries blur and where meaning arises from process, collaboration and tactile engagement.