A Beginner's Guide to Major Art Movements: Romanticism, Abstract Expressionism & Surrealism

Discover three transformative art movements that shaped visual culture. From Romantic emotion to Abstract Expressionist innovation and Surrealist unconscious exploration, understand how artists responded to historical upheavals through revolutionary expression.

Understanding art history can seem daunting, but exploring major art movements provides essential context for appreciating how artists have responded to their times and shaped visual culture. Three particularly influential movements—Romanticism, Abstract Expressionism, and Surrealism—each emerged from distinct historical moments yet continue to influence contemporary art today. This guide offers accessible introductions to these transformative movements, helping you understand their origins, key characteristics, and lasting impact.

Romanticism

Origins and Historical Context

Romanticism emerged as an artistic and intellectual movement in Europe during the late 18th century and flourished until the mid-19th century. First defined as an aesthetic in literary criticism around 1800, it gained momentum as an artistic movement in France and Britain during the early decades of the 19th century. The movement developed as a direct response to the Enlightenment's emphasis on reason and order, particularly following the disillusionment that came after the French Revolution of 1789.

The movement's purpose was fundamentally reactionary—Romanticists rejected the social conventions of their time in favour of individualism, arguing that passion and intuition were crucial to understanding the world. They believed that beauty transcended mere form and should evoke strong emotional responses, marking a significant departure from the calculated rationalism of the preceding era.

Key Characteristics and Themes

Romanticism was characterised by several defining features that set it apart from earlier artistic traditions. The movement emphasised emotion over reason and celebrated individual imagination and intuition. Artists focused on the individual experience and subjective perception rather than objective reality or accuracy.

Nature played a central role in Romantic art, with artists exploring the beauty and power of the natural world. They often depicted landscapes, flora, and fauna in highly stylised and idealised ways, using bold brushstrokes and vibrant colours to convey intense experiences. This connection to nature related directly to the eighteenth-century aesthetic of the Sublime, as articulated by British statesman Edmund Burke in 1757: "all that stuns the soul, all that imprints a feeling of terror, leads to the sublime".

The Romantics also harboured a particular fondness for the Middle Ages, which they viewed as an era of chivalry and heroism that represented a more organic relationship between humans and their environment. This idealisation contrasted sharply with their contemporary industrial society, which they considered alienating due to its economic materialism and environmental degradation.

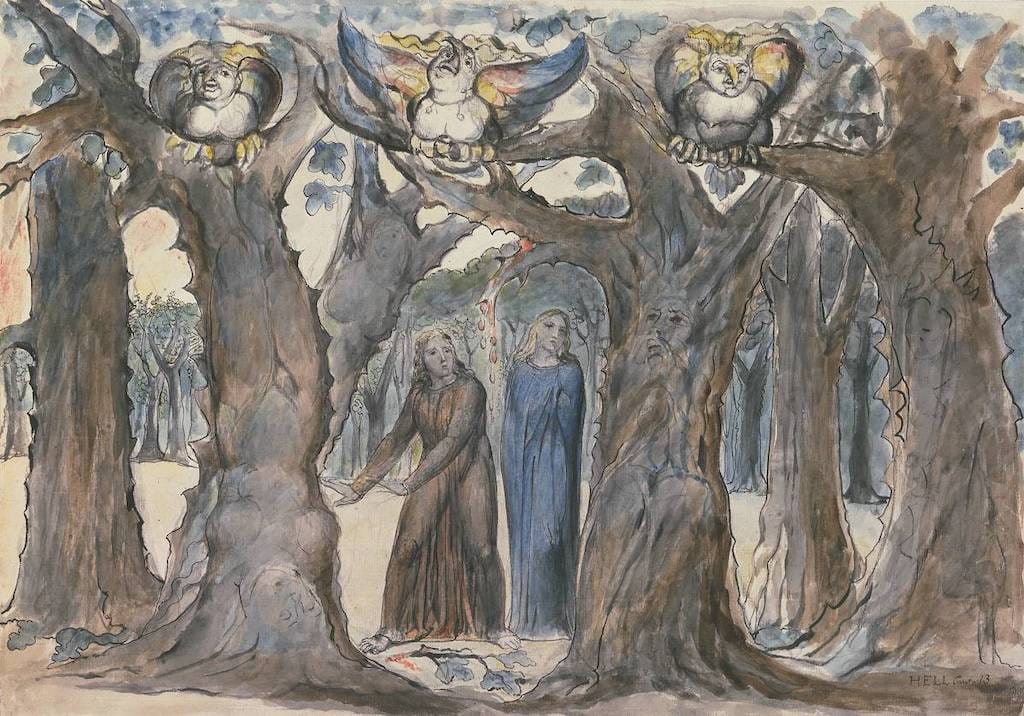

Supernatural and mysterious elements frequently appeared in Romantic works, reflecting a fascination with the unknown and unseen. Many artists explored themes of death and mortality, incorporating ghosts, demons, and otherworldly creatures into their compositions.

Notable Artists and Their Contributions

The Romantic movement produced several influential artists whose works continue to inspire today. William Blake merged poetry and visual art to create mystical, symbolic works. Eugène Delacroix became renowned for his dramatic, emotionally charged paintings that exemplified Romantic ideals of passion and individual expression. Francisco Goya explored the darker aspects of human nature and social criticism through his haunting works.

J.M.W. Turner revolutionised landscape painting with his atmospheric, light-filled canvases that seemed to dissolve form into pure colour and emotion. Caspar David Friedrich created contemplative landscapes that often featured solitary figures confronting sublime natural scenes, perfectly embodying the Romantic preoccupation with individual experience and nature's power.

These artists shared a commitment to asserting the originality of the artist—a central notion of Romanticism that challenged traditional academic conventions.

Abstract Expressionism

Historical Context and Origins

Abstract Expressionism emerged in New York during the 1940s and 1950s, representing America's first major contribution to international avant-garde art. The movement developed against the backdrop of World War II and its aftermath, when many artists felt they could no longer continue painting traditional subjects after witnessing the war's horrors.

Political instability in 1930s Europe brought several leading Surrealist artists to New York, profoundly influencing the developing Abstract Expressionist movement. These immigrant artists brought ideas and practices of European Modernism, teaching American artists about Cubist formal innovations and Surrealist automatism and psychological underpinnings.

The movement was shaped by artists who had matured during the 1930s and were influenced by the era's leftist politics, coming to value art grounded in personal experience. As artist Barnett Newman explained: "We felt the moral crisis of a world in shambles, a world destroyed by a great depression and a fierce World War, and it was impossible at that time to paint the kind of paintings that we were doing—flowers, reclining nudes, and people playing the cello".

Defining Characteristics

Abstract Expressionism was characterised by several shared traits despite encompassing diverse individual styles. The works were usually abstract, depicting forms not found in the natural world, and emphasised freedom of emotional expression, technique, and execution. Artists created single unified, undifferentiated fields, networks, or images in unstructured space, and the canvases were typically large to enhance visual effect and project monumentality and power.

Two main tendencies emerged within the movement: action painting and colour field painting. Action painters focused on the physical act of painting itself, using splashing, dripping, and gestural brushstrokes rather than carefully applied paint. Colour field painters created simple compositions with large areas of usually single flat colours designed to produce contemplative or meditative responses.

The Abstract Expressionists were deeply influenced by Surrealist ideas about exploring the unconscious, as well as by Swiss psychologist Carl Jung's theories about myths and archetypes. They also gravitated towards existentialist philosophy, expressing emotions and universal themes through often monumental canvases in a style that fitted the post-war mood of trauma and anxiety.

Major Artists and Techniques

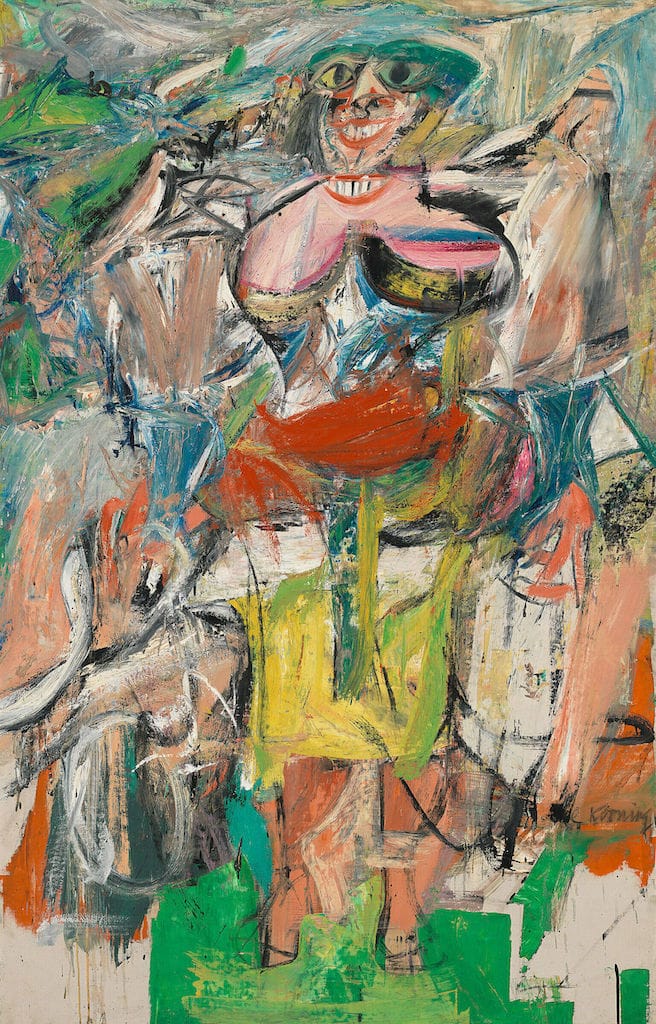

Jackson Pollock became the most famous action painter with his revolutionary drip paintings, creating works by moving around large canvases placed on the floor and allowing paint to fall in controlled yet spontaneous patterns. Willem de Kooning developed a vigorous gestural style that often incorporated fragmented human forms.

Among the colour field painters, Mark Rothko created luminous, meditative works featuring large rectangles of colour that seemed to glow from within. Barnett Newman developed his signature "zip" paintings—large colour fields interrupted by vertical lines—whilst Clyfford Still created jagged, cliff-like forms in bold colours.

Lee Krasner, initially overshadowed by her husband Pollock, developed her own distinctive abstract style and played a crucial role in the movement's development. Other significant figures included Franz Kline with his bold black-and-white compositions, Helen Frankenthaler who pioneered stain painting techniques, and Robert Motherwell who explored automatic drawing methods.

Cultural Impact

The success of Abstract Expressionism marked a historic shift in the art world. These New York painters "robbed Paris of its mantle as leader of modern art, and set the stage for America's dominance of the international art world". The movement established New York as the new centre of avant-garde art and demonstrated that American artists could create work of international significance and influence.

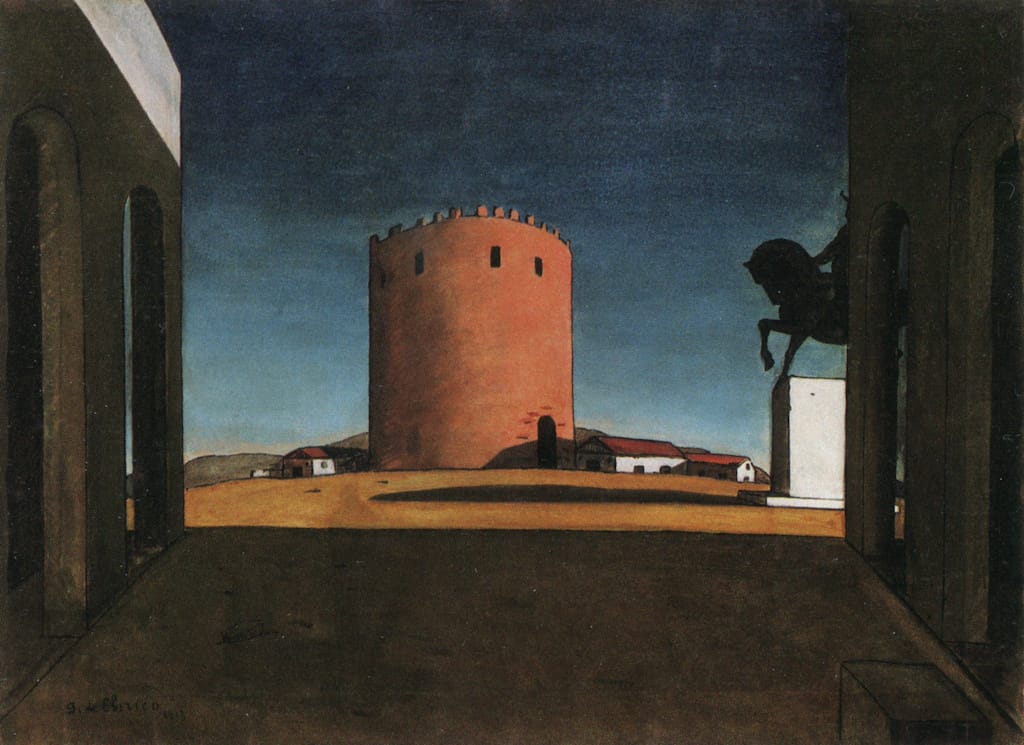

Surrealism

Origins and Philosophical Foundations

Surrealism developed in Europe following World War I, officially established in October 1924 when André Breton published the Surrealist Manifesto. Though the term originated with Guillaume Apollinaire in 1917, it was Breton who defined the movement's goals and philosophy.

The movement's central aim was to allow the unconscious mind to express itself, often resulting in illogical or dreamlike scenes and ideas. According to Breton, Surrealism sought to "resolve the previously contradictory conditions of dream and reality into an absolute reality, a super-reality," or surreality.

Surrealism grew principally out of the earlier Dada movement, which had produced works of anti-art that deliberately defied reason. However, Surrealism developed specifically in reaction against the "rationalism" that had led to World War I. The movement was explicitly revolutionary, associated with political causes such as communism and anarchism.

Key Concepts and Techniques

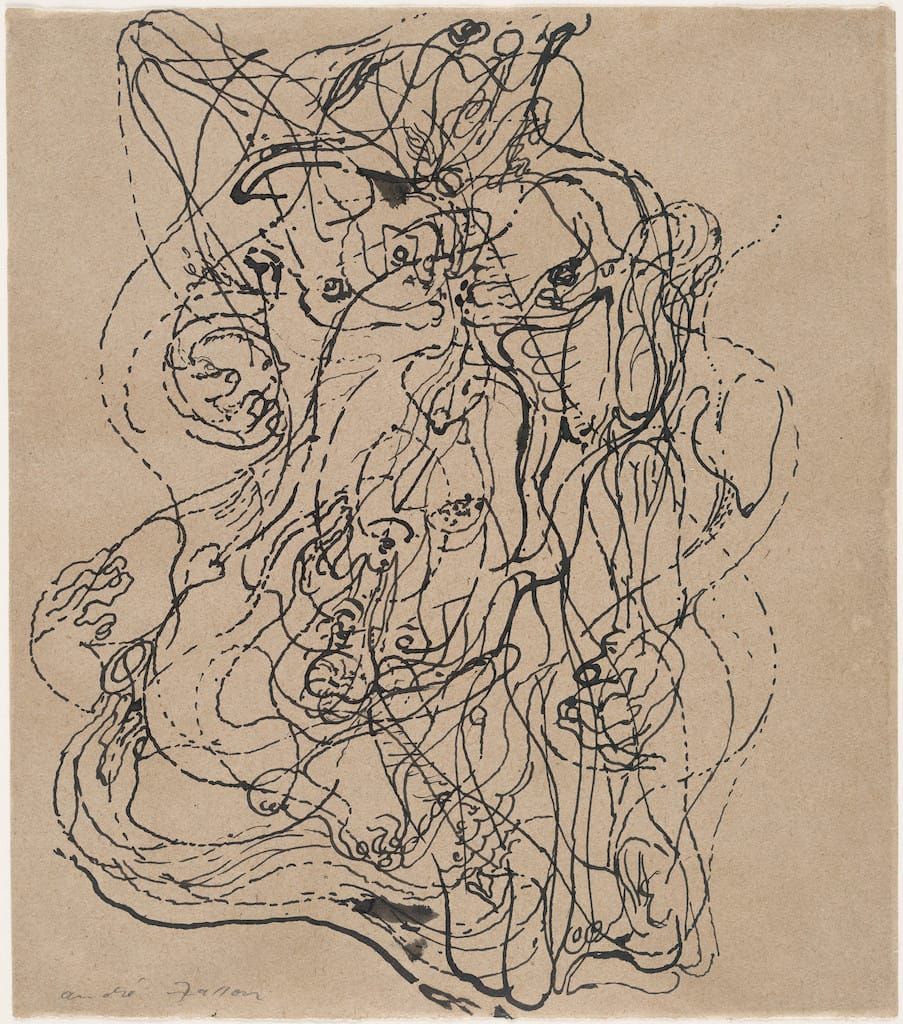

Automatism became a fundamental Surrealist technique—what Breton defined as "psychic automatism in its pure state, by which one proposes to express - verbally, by means of the written word, or in any other manner - the actual functioning of thought". This technique allowed artists to bypass reason and rationality by accessing their unconscious minds, embracing chance when creating art.

The influence of Sigmund Freud was profound for Surrealists, particularly his book "The Interpretation of Dreams" (1899). Freud legitimised the importance of dreams and the unconscious as valid revelations of human emotion and desires, providing theoretical basis for much Surrealist work.

Surrealist works featured elements of surprise, unexpected juxtapositions, and non sequitur. However, many Surrealist artists regarded their work as expressions of philosophical movement first, with the artworks themselves being secondary artifacts of surrealist experimentation.

Artistic Approaches and Imagery

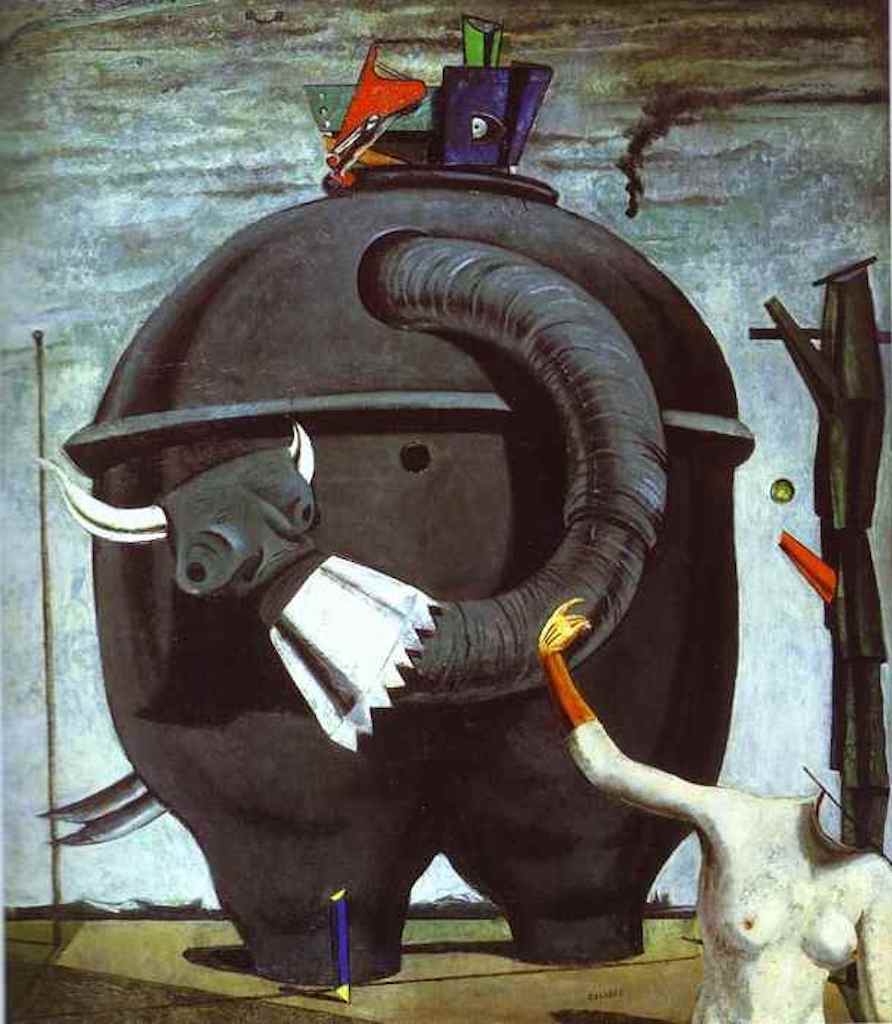

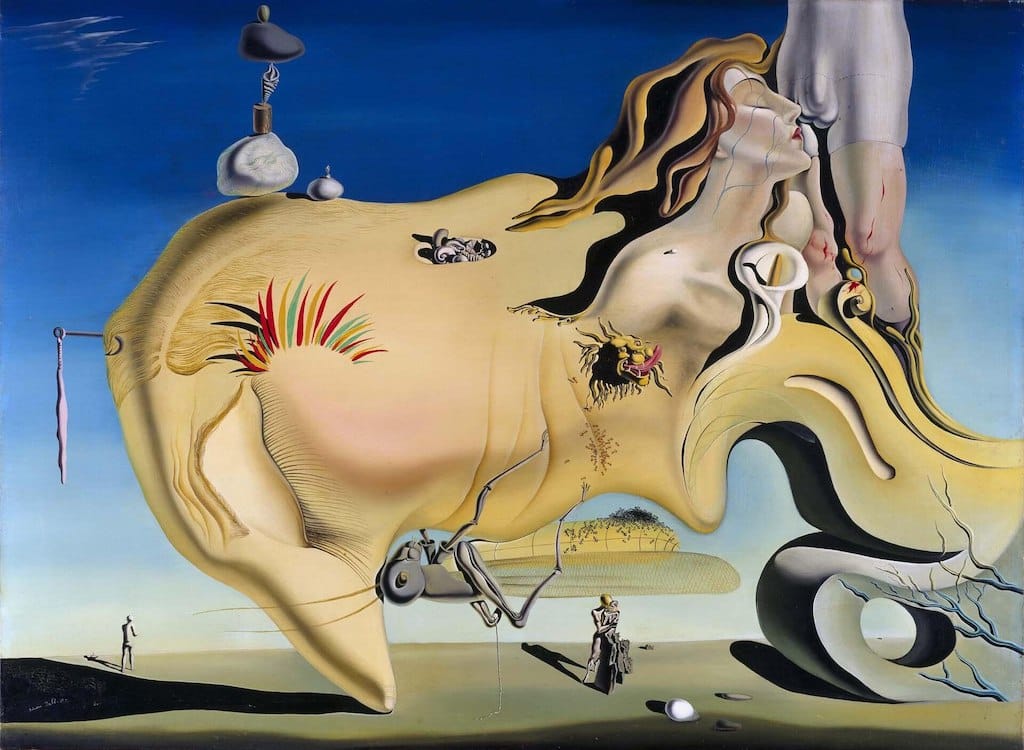

Two main approaches emerged within Surrealism: some artists practiced organic, emblematic, or absolute Surrealism, expressing the unconscious through suggestive yet indefinite biomorphic images. Artists like Jean Arp, Max Ernst, André Masson, and Joan Miró fell into this category. Others created realistically painted images removed from their context and reassembled within paradoxical or shocking frameworks—most notably Salvador Dalí and René Magritte.

Surrealist imagery, whilst recognisable, remains elusive to categorise definitively. Each artist developed recurring motifs arising through dreams or the unconscious mind. The imagery was typically outlandish, perplexing, and uncanny, designed to jolt viewers out of comfortable assumptions. Nature provided frequent inspiration: Max Ernst was obsessed with birds and developed a bird alter ego, Salvador Dalí's works often included ants or eggs, and Joan Miró relied on vague biomorphic imagery.

Global Influence and Legacy

From its Parisian centre, Surrealism spread globally from the 1920s onwards, impacting visual arts, literature, theatre, film, and music across many countries and languages. The movement also influenced political thought and practice, philosophy, and social and cultural theories.

Though the European Surrealist movement dissipated at the start of World War II, many Surrealist artists relocated to the United States, where the movement was reignited and continued to influence renowned visual artists throughout the 20th century. The Surrealist emphasis on personal imagination, myth, and primitivism shaped many later movements, and the style remains influential today.

Understanding Context and Continuity

These three movements—Romanticism, Abstract Expressionism, and Surrealism—demonstrate how artists have consistently responded to social, political, and cultural upheavals through innovative visual expression. Romanticism emerged from post-Enlightenment disillusionment, Abstract Expressionism from post-war trauma, and Surrealism from the psychological wounds of World War I.

Each movement shared certain characteristics despite their different historical contexts: emphasis on individual expression over academic convention, interest in the unconscious or emotional rather than purely rational, and willingness to break with established artistic traditions to address contemporary concerns.

Understanding these movements provides crucial insight into how art functions as both personal expression and social commentary, revealing how artists have continually pushed boundaries to create new visual languages capable of addressing their historical moments. Whether through Romantic celebration of individual emotion, Abstract Expressionist exploration of post-war anxiety, or Surrealist investigation of unconscious desires, these movements continue to influence contemporary artists seeking to understand and express the complexities of modern experience.

By familiarising yourself with these foundational movements, you'll develop a stronger appreciation for how artistic innovation emerges from historical necessity and continues to shape visual culture today.